Continuing professional development (CPD) is an important way of spreading evidence-informed practice (EIP) in schools. But despite widespread calls for more for teachers, most forms of CPD do not work. A review by Yoon et al. (2008) found 20 effect sizes reported from studies capable of identifying causal impacts, eight of which showed an effect on attainment, 12 of which showed no effect. Another review by Blank and Alas (2009), which used statistical techniques to combine 31 findings from different studies, found positive effects from maths CPD but no effect from science CPD. Education Endowment Foundation trials show equally mixed results (Hanley et al, 2016; Worth et al., 2015; McNally et al., 2014).

Why is CPD so often ineffective?

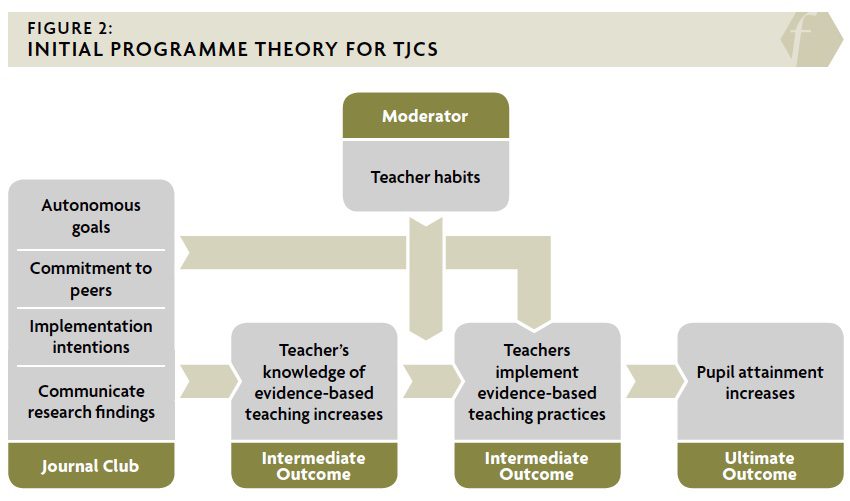

Most CPD is premised on the idea that informing teachers of research findings, or techniques informed by them, will allow teachers to implement these ideas in the classroom, which will then feed through into improved student attainment (see Figure 1). However, this model rests on a number of assumptions: link 1 requires that useful findings are communicated to teachers effectively, link 2 assumes that teachers will implement what they learn, and link 3 assumes that conditions in the school allow these actions to benefit student attainment. Failures of CPD are often explained by a failure of link 1 (Scott and McNeish, 2013). However, the linear nature of this model means that all three links need to be working if CPD is to improve attainment.

Of particular interest is link 2, since a range of evidence suggests the model is likely to break down here. Wiliam (2007) gives the example of research by Mary Rowe (1986), which shows that, if teachers wait two or three seconds after asking a question before accepting a response, students learn more. According to Wiliam this research was widely publicised and well known, but not generally acted upon by teachers. Why would teachers not implement this easy-to-use advice?

Wiliam suggests that habits are an important part of the explanation. Webb and Sheeran (2006) review 47 rigorous experimental studies and find that habits – automatic behaviours cued by our environment – are indeed the most important reason people fail to follow through on their intentions. Research suggests that teachers are particularly prone to habitual behaviour because classrooms are very stable environments, some aspects of the job are quite repetitive and teaching is quite stressful; all of which are conducive to habit formation (Wood and Neal, 2007; Schwabe and Wolf, 2010).

Teacher journal clubs: A way forward?

Journal clubs – traditionally used by medical doctors – are a regular cycle of meetings at which teachers discuss research. In each session, the participants summarise the findings of an article, critically discuss them, work in pairs to plan how they will incorporate them into their practice and then choose another article for the following meeting. In the following meeting, the session begins with participants feeding back and discussing their experience implementing their plans from the last session and what they have learned from the process, before moving on to the next article. Teacher journal clubs (TJCs) incorporate three important insights from the psychology literature on how to promote behaviour change in the face of habits:

- Implementation intentions are plans that include specific references to when and where the plan will be executed that have been shown to help change habitual behaviour (Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006). Implementation intentions are incorporated into the TJC format in the paired lesson planning exercise.

- Autonomously chosen goals are more effective at changing behaviour than goals given to us by others (Prestwich and Kellar, 2014). Autonomous goals are incorporated in TJCs in that teachers choose: whether to participate in the TJC, which articles to read and whether, what and how to implement what they have learned.

- Committing to change practice in the presence of others has also been shown to be a powerful support for behavior change (Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006). TJCs involve committing to change in front of professional peers through the paired lesson planning exercise, and then reporting back on progress.

Figure 2 incorporates the empirical findings discussed above, showing the moderating (weakening) role that habits have on link 2 and how the three active ingredients of TJCs discussed above help change practice.

Researching TJCs in practice

We set out to investigate the feasibility of running journal clubs in schools and test the accuracy of the theory set out in Figure 2. We set up TJCs in two schools during the 2015/16 school year. Both schools volunteered to take part after hearing the idea for TJCs presented at the 2015 ResearchEd conference. School A is an 11-18 mixed school in outer west London, rated by OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – a non-ministerial department responsible for inspecting and regulating services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills as outstanding and has an average number of students on free school meals (FSM). School B is an 11-18 mixed school in Bristol rated outstanding by Ofsted and has around twice the national average of FSM students. Teachers within the schools volunteered to take part: seven in School A and 10 in School B. The authors collated a set of recent narrative review articles for participants to choose from, based on their interests. Topics included spacing, interleavingAn approach to learning where, rather than focusing on one piece of content at a time (known as blocking) then moving on to the next, students alternate between related concepts, retrieval practice, feedback, worked examples, inference and student motivation. Data was collected through observations, a short questionnaire and interviews.

School A met seven times during the year and School B five times. Data from the observations suggested that teachers were able to engage with and critically discuss the articles. For example, in one session, participants discussed whether and how research on feedback conducted with post-secondary students was applicable in their school. In another, the recommendations of an article on inference were discussed in relation to the perceived weaknesses of previous government literacy strategies.

Both TJCs engaged in communal planning around how the research could be applied in the classroom, including sharing existing evidence-aligned practice. In School A, teachers shared a questioning grid that one of the teachers had previously developed and several other teachers then used this before the next meeting. Although both TJCs worked together to discuss how the ideas from the articles could be applied, they preferred to do this as a group, rather than in pairs. One teacher explained: ‘The discussion has been useful, but the planning I want to do myself… I want to influence the student’s learning in different ways’ (A3). Because specific planning did not take place in the TJC, implementation intentions are dropped from our revised model (see Figure 3). Both TJCs also shared feedback on how they applied research findings in class and, in School A, teachers sometimes presented evidence of the quality of students’ work before the changes they made. Time pressures occasionally meant teachers were unable to participate. Nevertheless, taken together this evidence demonstrates TJCs are feasible.

Testing the programme theory

To test the programme theory, we asked participants how the TJC differed from normal CPD programmes. Several noted that they applied more of the ideas from the TJC. When asked why, participants alluded to the working environment: ‘School life dissuades you from doing anything different, because it’s easier to just do more of the same. There’s safety in routine’ (B3). Another mentioned habits directly: ‘You get into habits with everything. To be jolted out of that is quite difficult’ (B2). One English teacher (A1) mentioned in their survey response that they were using a series of low-stakes quizzes to exploit the benefits of retrieval practice. At the end-of-year interview, they confirmed they were still using the quizzes and had been asked to rewrite the scheme of work to embed the approach across the department.

In addition to habits, another theme emerged as to why EIP is often not adopted. Many effective teaching techniques are hard to use and this can lead teachers to erroneously conclude that the techniques are ineffective. One of the journal articles covered peer assessment techniques in which students mark each other’s work. Two teachers had tried this before but it hadn’t worked well. ‘I’ve always shied away from it because in the past my experience has always been that students didn’t give each other good feedback – it was always very surface-level’ (A1). Another teacher noted how students will complain if they think a new teaching method doesn’t work: ‘When it’s just you against fifteen kids – it’s hard to follow through’ (B3). However, being able to share feedback helped participants refine their approach. For example, teachers shared a peer assessment checklist which students could use to prompt more in-depth feedback. As teacher A2 explained: ‘Just having that sharing of ideas… you can try it again and set it up in a different way.’

Writing off an effective technique because it is hard to use has been termed the ‘hot stove effect’ in the psychology literature (Denrell and March 2001: p.523), following Mark Twain’: ‘We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it – and stop there: lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again – and that is well; but also she will never sit down on a cold one.’

Computer simulations and experiments with real people have shown that the hot stove effect can have a powerful influence on whether people adopt good ideas (Denrell and March, 2001; Fukijawa, 2009). Observations revealed, for example, how teacher A6 initially had little success using the questioning grid to develop inference skills, but then adapted it successfully based on feedback from other teachers. Teacher A1 explained how commitment to peers also helps to overcome the hot stove effect: ‘In a big group of people you get “Oh yeah, it works for your classroom but it wouldn’t work for my class”, but having that discussion time, we’ve been able to encourage, support, challenge each other to say “Could you not use it in this way?” or “Could you not adapt it in that way?”’ We add the hot stove effect to our model in Figure 3.

Teacher B2 noted how the voluntary nature of the TJC changed the way they approached it: ‘I think you just value it more… It gives you more ownership.’ Another (A5) highlighted how choosing which material they studied also helped: ‘When we have all-staff Inset, you’re sort of being talked at and you’re listening. It’s done because there’s a certain drive or idea or theme… In a small group… you’re more in control of it, you can use this and reject that.’ Teacher A1 also stressed the importance of autonomy: ‘We have far more understanding of why we are doing something. It makes people more motivated to go away and try something… or go back and revisit something they’ve tried.’ The importance of working with peers also emerged. ‘I think because it’s a small group I think you do it more [change practice] than if it were a big group, when you might think, I don’t have time. I think because it’s a small group you have responsibility to each other and if nobody does it it’s embarrassing and it’s a waste of time. This CPD is for us, it’s not for other people.’ (A6). The importance of both autonomy and commitment to peers in changing habitual behaviour were therefore both confirmed by our data.

Observations and interviews also highlighted the importance of getting the right kind of article. Carpenter (2014) embodied many desirable characteristics. It was relatively short (eight pages); provided an overview of evidence while describing two important studies in more detail; introduced and clearly defined a limited number of concepts; clearly identified the most effective approach; and focused on improving memory, which was highly relevant at the time the linear exam specifications were being introduced. Where articles displayed few of these features, teachers were sceptical that the exercise had been valuable: ‘Some of the other articles, either we weren’t able to access them because they had lots of long words in, or they didn’t have any practical implications… If I’m honest, I don’t think those ones were massively successful’ (B5). Following this evidence, we also add the quality of articles as a moderator to our final model in Figure 3.

Conclusion

This research cannot tell us whether TJCs have a positive effect on student attainment. That would require an experimental or quasi-experimental evaluation, which we hope to conduct in future work. It does however show that TJCs are a feasible model for teacher CPD. It also illuminates two important reasons that CPD is so often ineffective – habits and hot stove effects – which suggest that increasing the flow of information to teachers (link 1), may be insufficient for improving EIP. The research also provides proof-of-concept for TJCs by showing how they help address these barriers in order to strengthen Link 3, and by documenting specific examples of how participation has led to sustained increases in EIP among participating teachers.

References

Blank RK and De Las Alas N (2009) The Effects of Teacher Professional Development on Gains in Student Achievement. Washington DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Carpenter SK (2014) Spacing and interleaving of study and practice. In: Benassi VA, Overson CE and Hakala CM (eds) Applying Science of Learning in Education: Infusing Psychological Science into the Curriculum. Society for the Teaching.

Denrell J and March JG (2001). Adaptation as information restriction: The hot stove effect. Organization Science 12(5): 523–538.

Fujikawa T (2009). On the relative importance of the hot stove effect and the tendency to rely on small samples. Judgment and Decision Making 4(5): 429.

Gollwitzer PM and Sheeran P (2006) Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A metaanalysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38: 69–119.

Hanley P, Slavin R and Elliott L (2015). Thinking, Doing, Talking Science: Evaluation Report and Executive Summary. Oxford: Education Endowment Foundation.

McNally S, Challen A and Wyness G (2014) Hampshire Hundreds: Evaluation report and Executive Summary. Oxford: EducationEndowment Foundation.

Prestwich A and Kellar I (2014) How can the impact of implementation intentions as a behaviour change intervention be improved? European Review of Applied Psychology 64(1): 35–41.

Rowe M (1986) Wait time: Slowing down may be a way of speeding up! Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1): 43–50.

Schwabe L & Wolf OT (2010) Socially evaluated cold pressor stress after instrumental learning favors habits over goal-directed action. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(7): 977–986.

Scott S and McNeish D (2013) School Leadership Evidence Review: Using Research Evidence to Support School Improvement. London: Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England.

Webb TL and Sheeran P (2006) Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysisA quantitative study design used to systematically assess the results of multiple studies in order to draw conclusions about that body of research of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin 132(2): 249.

Wiliam, D (2007) Changing classroom practice. Educational Leadership 65(4): 36–42.

Wood W and Neal DT (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4): 843.

Worth J, Sizmur J, Ager R and Styles B (2015) Improving Numeracy and Literacy Evaluation. Oxford: Education Endowment Foundation.

Yoon KS, Duncan T, Lee S and Shapley K (2008) The effects of teachers’ professional development on student achievement. American Educational Research Association annual meeting, March.