Developing subject expertise in primary

This case study is written by Robbie Burns, a primary school teacher and humanities leader.

As you read this case study, reflect on the approaches suggested for developing subject expertise and consider how the approaches might be relevant to your own development as an early career teacher.

In this case study, I hope to explain the three strands of subject specific expertise, describe some practical steps I have used to develop them and suggest some resources that you can use to further your understanding. I do suggest some resources that you might have to pay for. In most cases, you shouldn’t be expected to pay for the ‘paid resources’ I suggest here. Talk to your NQT/RQT mentor and see if you can get anything you pay for reimbursed. Some of the resources might already be paid for by the school, such as subject associations. If this is the case, speak to the subject leader who is in charge of the subject and they may be able to give you a log in.

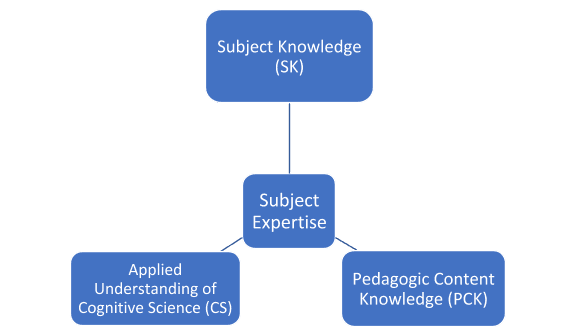

Subject specific expertise can be broken down into three parts. As I will allude to throughout this case study, it is my view that as primary teachers, it is impossible to be an ‘expert’ in the normal sense of the term in every single subject of the curriculum. However, as your career progresses, it is possible to incrementally develop your understanding of each subject so that you are competent at delivering a broad and balanced curriculum in a range of year groups.

This takes time, energy, effort and lots of reflection. When I first started teaching, I felt quite overwhelmed about having to teach such a diverse variety of subjects and felt completely unprepared to do so. Being able to break each subject of the curriculum down into three parts helped me think carefully about the strands that I could develop as I progressed. They are subject knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge and an applied understanding of cognitive scienceThe study of the human mind, such as the processes of though... More. The next part of this case study will explain each and describe practical steps I have used.

Subject knowledge

Recent pedagogy research confirms a common and longstanding understanding amongst experienced teachers about what makes good teaching: you cannot be an effective teacher without having secure subject knowledge of what you are teaching. Coe et al. (2014) goes as far as to say that it is actually the most important factor in good teaching; this is matched with research conducted by Rosenshine (2012), who in his principles for instruction assumes that teachers will know their lesson content before they teach.

The claims made above might be quite daunting to someone who has just begun teaching in a primary school. Despite what the research claims about subject knowledge, it is important to remember that it is impossible to know everything that you need to know about every subject in the curriculum before you start your first job.

Practical steps for developing subject knowledge:

- Be honest with yourself and your class that you will not be able to know everything. A good practical strategy for this is to have a ‘question box’ in your classroom, or a dedicated sheet at the back of exercise books where curious pupils can write down their questions that you don’t know the answer to. Then, after you have taught the lesson and you have time, you can go away and research the answers and feed that back to your pupils in the next lesson.

- Create a knowledge organiser for each unit of work you will be teaching. This enables you to have a clear, concise guide to the knowledge that your pupils will be learning and therefore, what you need to know. This process protects you from spending time researching information about the subject that might not be needed for your teaching. Focussing lessons on learning the declarative and procedural knowledge that you have planned ensures that you can feel confident with teaching what you do know about the subject. To understand the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ of knowledge organisers, see this blog post.

- Ask more experienced colleagues for support. As a new teacher, you must never be afraid to ask your colleagues for support. It is far better that you spend time developing your confidence with the knowledge that is needed to be learned than to teach it wrong or insecurely. Build strong relationships with more experienced colleagues and ask them to share their schemes of work, knowledge and understanding of the curriculum that you will be teaching in your year group.

Pedagogical content knowledge

Simply put, pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) is the reasoning, justifications and the wisdom that teachers develop (Shulman, 1987). It is the essence of the craft of teaching and differentiates the pedagogue from an encyclopedia, a textbook or a YouTube video. PCK is the thinking that teachers do in the classroom to support the learning of all their pupils. Where subject knowledge is the what, pedagogical content knowledge is the how. PCK, broken down further into its constituent parts is the explaining, modelling, questioning, noticing and nudging that teachers do, at exactly the right time and in exactly the right way. Unlike subject knowledge, it is difficult to pin down and find on a website. However, great strides in recent years have been undertaken to try and make what once seemed tacit more explicit to teachers.

I’ll never forget watching a colleague (who had been teaching longer than I’d been alive) explain adding fractions in Maths to a low attaining Year 6 group. I knew everything she knew and could ace a Year 6 SATs test but I couldn’t teach it like she did at that point in my career. Her explanations were crisp and clear; her modelling was absolutely seamless and the pace of the lesson was perfect. Throughout the lesson, she had her finger on the pulse of everything that went on in the room. She simply knew what to do and when to do it. She had deep pedagogical content knowledge.

How can you develop this as a teacher newly entering the profession? It comes with time. I think that’s my simplest answer. I am still developing it day by day. Every teacher is. However, just like the last strand of subject expertise, there are strands of PCK that you can break down and practice, so that you can develop.

Practical steps for developing pedagogical content knowledge

- Practice explaining and modelling key processes, knowledge and tasks with no pupils in the room. I still do this and I realise now it is one of the most powerful things that you can do to prepare for the day of teaching. Are you worried about explaining how to do long division? Practice it by yourself with no one around, imagining that your class is right there sat in front of you. Visualise what pupils might ask, what misconceptions they might have and how you might answer them.

- Practice explaining and modelling key processes, knowledge and tasks with a more experienced colleague watching. If you have a mentor, ask them if they have ten minutes, if they can help you prepare your explanations, your modelling, your lesson. If you have a good relationship with them, this will become a powerful confidence boost for you but also build your pedagogical content knowledge over time.

Applied understanding of cognitive science

This final strand of developing subject specific expertise relates to more general principles of teaching that cognitive science research suggests make an effective classroom climateThe social, emotional, intellectual and physical environment... More, regardless of the subject being taught. There are many insights and practical resources for making sense of the research out there and this might at first seem overwhelming to you as you try and develop your understanding of the other two strands. However, there are few key distinctions you ought to know about as you consider the other two strands that have hugely helped me in my teaching. These relate to the way you organise your lessons and how you can make sure your pupils are able to pay attention and remember what they learn. Below is a really brief explanation of both to support your development.

Helping pupils remember: working and long-term memory

Cognitive science research in recent years has led us to consider what is now called ‘the simple view of memory’ as a helpful way to think about how we develop our lessons so that pupils can remember as much as possible. In summary, we can only hold a maximum of 7 items in our working memory at any one time, any more information than this and we make mistakes, forget facts we are being presented with or do things incorrectly (Miller, 1956). Unlike working memory, long-term memory has the potential for an unlimited store of information. For a more detailed explanation of this, see this open-access paper.

With this in mind, if our lessons overload our pupils with too much information, it is likely that they will not be able to commit to long term memory what they are learning in our classrooms. Therefore, we need to be careful how much information we present our pupils with and also be sure to present it in the right order, explained carefully, in small steps.

Helping pupils pay attention: cognitive load theory

The above model of memory is built upon by Sweller et al. (2019) to propose cognitive load theoryAbbreviated to CLT, the idea that working memory is limited ... More. Quite simply, if we are presenting new information to our pupils, we need to be careful not to overload their working memory, since their cognitive architecture is trying to process the new information and assimilate it with what is already in their long-term memory. So, if you present too much new information, or don’t break down tasks carefully, it is likely that new learning will not be remembered and the attention of your pupils on what you want them to learn is unlikely to be as focussed as you’d like it to be.

Practical steps for developing an applied understanding of cognitive science

- Develop your knowledge of cognitive science and its application to the classroom. For more details about how to do this, look at the resources section of this case study.

- Think carefully about what is included in each lesson and reflect on whether it might overload your pupils. Use these questions to help you: How much ‘new’ knowledge is being learned in this lesson? How will I be explaining this? How am I breaking this down into small steps? How will I check that my pupils understand what I am teaching them?

Resources for each strand

Subject knowledge

Websites

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize – Several videos, explanations and web pages explaining subject specific knowledge. I have sometimes found it helpful to look at the key stage above what I’m teaching also, just so I’m aware of ‘what’s next’ in my pupils’ learning.

- YouTube channels (variety) – I regularly use YouTube channels that explain science concepts, Maths operations and grammar terms. Just simply type in at the top of the search bar on this website and peruse the videos available – (be careful though, some of these videos will use American terms and not be matched to the national curriculum)

- https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100607215842/ and http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/schemes3/subjects/?view=get – QCA Documents of previous national curriculum schemes of work. Although these documents form part of an old national curriculum, they are still helpful in making sense of what you need to know in each subject. Be careful though, some objectives may no longer be included.

- https://www.ncetm.org.uk – An excellent, free website for Maths teaching. Log in required.

- https://www.stem.org.uk – An excellent, free website for Science, D&T and Engineering. Log in required.

Paid resources

- Subject associations – probably the most useful resource that is worth paying for. By accessing the resources from the subject associations, you are tapping into ‘the best of what has been thought and said’ in that subject. The great thing about resources from these organisations is that they are highly trusted and respected.

- CGP books – These are useful revision guides, set out in simple ways for you to use in your teaching. They can be purchased for a small fee.

- Old text books – On Amazon it is possible to find old textbooks that can be purchased cheaply. These often have helpful, short explanations and diagrams for complex terms.

Pedagogical content knowledge

This is trickier to find online and read about. However, here are some ideas and suggestions to consider after you have had support from your colleagues.

- Research ‘misconceptions’ in a particular subject, to make yourself aware of aspects of the subject that some pupils might find difficult.

- Watch YouTube videos of teachers explaining key knowledge, processes and concepts and use this as a guide for how to teach and explain.

- Look at a variety of curriculum documents and analyse how they have sequenced knowledge, skills and understanding. Progression documents are particularly helpful for understanding this more fully.

Applied understanding of cognitive science

There is a wealth of free online resources for developing your understanding of cognitive science. Here are the two best websites to start your research in this area.

- There are free downloadable materials you can use here.

- https://www.retrievalpractice.org – A great website focussed on a key aspect of learning science. Lots of free resources available here, too.

- Two books that are highly readable I would recommend as an introduction to cognitive science in education would be: Willingham, D. (2009) Why Don’t Students Like School? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. and Weinstein, Y, Sumeracki, M, Caviglioli, O. (2018) Understanding how we learn: A visual guide, Routledge: London.

Click here to access your book discount codes as a Chartered College of Teaching member.

References

- Coe R, Aloisi C, Higgins S and Major L E (2014) What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research. London: The Sutton Trust.

- Miller G A (1956) ‘The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information,’ Psychological Review 63(2): 81–97.

- Rosenshine B (2012) Principles of Instruction: research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator 36 (1) pp. 12-19, 39.

- Sweller J, van Merriënboer J and Paas F (2019) Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later. Educational Psychology Review.

- Shulman L S (1987) Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review. February. 1987: 1-22.