Life-worthy learning skills: A curriculum intervention to promote self-regulated learning

Why this? Why now? Why us?

Jerome Bruner, the renowned American psychologist, states that the primary objective of any act of learning, over and beyond the pleasure it may give, is that it should serve us in the future (Bruner, 1960). The purpose of education is therefore to prepare young people for the future. However, the future for young people currently studying in today’s education system is increasingly uncertain. Today’s learners will emerge from the relative safety of school into a constantly evolving social, political and technological landscape. As such, how best do we, as teaching practitioners, prepare pupils for the unknown? What do they need to know or be able to do? Nilson (Nilson, 2013) argues that only lifelong learners will be able to keep pace with the explosive growth in knowledge. At St Edward’s, we believe that in a dynamic society that demands lifelong learning, we should be helping our pupils to develop the ability to regulate their own learning.

Schunk and Zimmerman (Schunk and Zimmerman, 1998) describe a self-regulated learner as someone who actively engages with their learning environment, uses resources effectively, organises and rehearses key information and holds positive motivational beliefs about their capabilities and the overall value of learning. Self-regulated learning (SRL) is a key competence for both higher academic education and future life, and should therefore play an important role in secondary education (Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2015); (Ewijk et al., 2013). However, SRL as a construct is relatively underused in practice, illuminating the gap that exists between research and practice that so many authors have outlined and the Chartered College of Teaching seeks to bridge. Our curriculum attempts to foster the development of pupils’ SRL skills whilst still equipping them with the knowledge and understanding they need to achieve excellence in public exams. It is founded on Zimmerman’s (Zimmerman and Zeidner, 2000) cyclic model of SRL whilst also drawing on the school’s academic aims and philosophy.

Zimmerman’s cyclic model of self-regulated learning

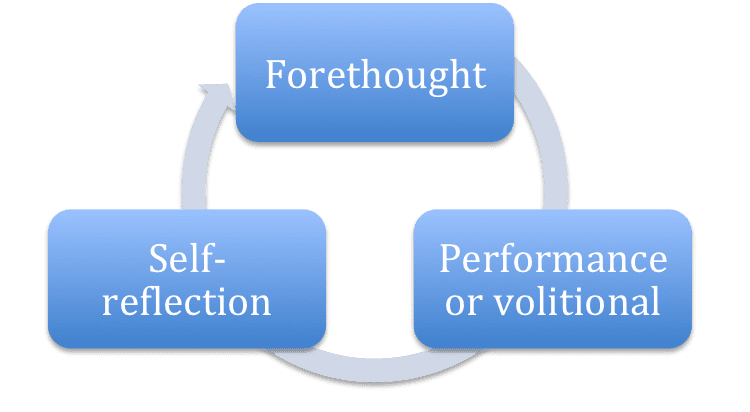

An SRL perspective places the student at the centre of the learning process and in doing so, allocates a significant amount of responsibility to the pupil for both the learning processes and outcomes (Stoten, 2015); (Zimmerman, 1998); (Zimmerman and Zeidner, 2000) developed a model of SRL that stems from Bandura’s (Bandura, 1986) social cognitive theoretical framework. Over the last 25 years, this model has served as a cornerstone in SRL research (Dunn and Lo, 2015), and forms the theoretical foundations for many SRL intervention studies (Dörrenbächer and Perels, 2016); (Perels et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 1, Zimmerman’s model of SRL is characterised by three cyclical phases that occur across a learning cycle.

In the first phase, forethought, influential processes that precede learning efforts ‘set the stage’ for learning. The second phase, the performance or volitional phase, involves processes that occur during learning efforts and affect concentration and action. The third phase, self-reflection, involves processes that occur after learning efforts, the outcomes of which feedback into the forethought phase forming the start of the next cycle. A summary of the phase structure and sub-processes occurring within each phase can be seen in Table 1.

Current Project: Research questions and design

This study investigates the impact of a curriculum intervention designed to enhance students’ SRL skills. It addresses following research questions:

- To what extent can a curriculum intervention enhance students’ SRL skills?

- Is there a significant difference in the summative achievement of those that received the intervention and those that did not?

This research is based on a quasi-experimental design model that employs a pre-test post-test non-equivalent group design (Cohen et al., 2013). The participants are from Year 9 having gained their voluntary informed consent (n=132). The year group has been divided in two by way of purposeful sampling (Bryman, 2012), using the existing school structure of six forms, therefore having three forms in each non-equivalent group. Before the intervention both Group A and B completed the two surveys used to measure SRL (dependent variable), the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Pintrich et al., 1991); (Pintrich et al., 1993), and the Self-Regulated Learning Experimental Design Survey (SRLEDS) (Turner, 2017). Group A received the intervention first, which takes the form of a ten-session training programme delivered within the formal teaching timetable and is designed to be a practical representation of Zimmerman’s cyclic model of SRL. At the end of the first phase of the intervention participants completed both the MSLQ and the SRLEDS in addition to the collation of their academic attainment marks across maths and the three sciences; biology, chemistry and physics. Group B then received the ten-session intervention with the two surveys completed for a third and final time at the end of the second phase along with the end of term test data across the aforementioned curriculum areas.

What’s next?

Once the two phases are complete the data will be checked for normality and analysed. Using SPSS, the data will be comprehensively analysed through a raft of descriptive statistics (measures of central tendency, dispersion, kurtosis and skewness) and robust statistical techniques including independent samples t-tests, mixed ANOVAs. The effect size will also be calculated using Cohen’s d. Next academic year (2018/19) will see the evolution of the Teddies Curriculum, which, based on the findings of this cycle, may include changes in the intervention itself as well as the use of a structured learning diary alongside the intervention to provide further support for the development of pupils’ SRL skills.

Closing comments

Returning to the words of Jerome Bruner cited at the start of this article, the primary objective of any act of learning is that it should benefit us in the future. Through the successful combination of the forensic approach of research with the progressive and pupil-centred goals of practice, we have designed and implemented a theoretically founded curriculum intervention that we believe will foster the development of pupils’ SRL skills. As educators there are two exciting and dynamic worlds in which we operate: inside our schools and outside in wider society. This is the same for our pupils and our aim is to provide the best possible preparation on the inside, so that pupils can flourish and thrive in the constantly shifting sands of contemporary society.

References

This article was published in February 2018 and reflects the terminology and understanding of research and evidence in use at the time. Some terms and conclusions may no longer align with current standards. We encourage readers to approach the content with an understanding of this context.