JEMIMA DAVEY, ASSOCIATE HEAD OF SCHOOL PGCE (PRIMARY AND SECONDARY), ST MARY’S UNIVERSITY, UK

STEPHEN CRINALL, HEAD OF SCHOOL, LALEHAM C OF E PRIMARY SCHOOL, UK

Aims

This study set out to explore how carefully designed opportunities for professional reflection might contribute to meaningful growth for teachers working in a challenging yet rapidly improving school. Against a national landscape marked by concerns about teacher wellbeing, retention and recruitment (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2024; Education Support, 2023), the project aimed to examine the potential of structured professional reflection to act as both a protective factor for staff and a driver of sustained professional development (Hughes, 2025). Specifically, the research sought to investigate how embedding reflective routines within a programme of continuing professional development (CPD) could support individuals to navigate the demands of their roles and strengthen their practice.

The study took place in a larger than average all-through primary school (educating children from the ages of two to 11) in West London, serving an area of deprivation and disadvantage. The community includes higher than average proportions of pupils eligible for pupil premiumAdditional funding for publicly funded schools in England to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils of all abilities, children with EAL (English as an additional language) and pupils with SEND (special educational needs and disabilities). In recent years, the school had experienced significant turbulence, including staffing turnover and an almost complete change in leadership. Following a period of rapid improvement (moving from a self-evaluation and local authority judgement of ‘inadequate’ in October 2022 to a secure OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – a non-ministerial department responsible for inspecting and regulating services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills judgement of ‘good’ in all areas the following autumn term), the leadership team recognised the need to consolidate the progress made by investing in the longer-term wellbeing and growth of staff. By considering their approach to ensuring the holistic development of students, school leaders saw the project as an opportunity to apply the same principles to staff development. The reflective routines shared with staff were woven into the school’s CPD plan, positioning reflection not as an additional burden but as a meaningful area of professional growth.

Methods

Data collection for this study focused on the individual experience of staff involved in a series of sessions exploring reflective practice in education. Over the course of three school terms, a whole-staff team was introduced to the theory of reflective practice, an exploration of the self within reflection and a consideration of research literature as a stimulus for reflecting on practice (Davey and Chambers, 2025).

The three sessions above were embedded within the whole-school programme for continuing professional development, meaning that all staff were involved in the sessions. Participants in the study were recruited on a voluntary basis and all staff were invited to take part in the research. In total, six teachers were involved in the study and represented a range of teaching experience and leadership roles.

Participants were invited to complete independent written reflections throughout the study, providing an opportunity to reflect on events in their professional lives. Prompts to support reflection included situations that elicited an emotional response and their impact, how these events may be viewed by colleagues and the influence of the reflective process on their future practice.

At the conclusion of the CPD sessions, participants were invited to semi-structured interviews. Questions prompted individuals to share how reflective practice had informed their professional role, when it had been most useful to them, how they had experienced the process and how it might inform their future practice. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, which allowed for thematic analysis to explore emergent themes from both individuals and the group (Braun and Clarke, 2021).

Analysis

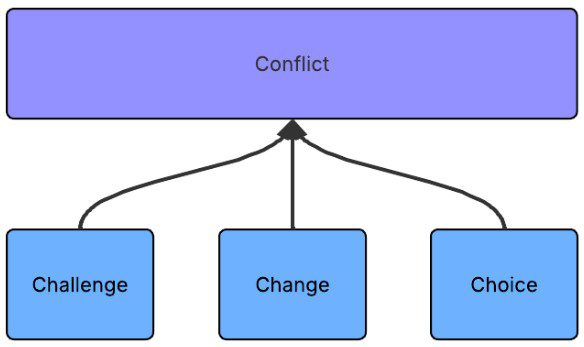

From the initial analysis, there were four key emergent themes that could be identified through the participant responses: challenge, change, choice and conflict (see Figure 1). While challenge, change and choice emerged consistently across interviews, conflict appeared to operate at an overarching level, with participants describing engaging in acts of reflection in moments of tension or difficulty.

Figure 1: Emerging themes from participants’ responses

Challenge

The theme of challenge featured strongly in the semi-structured interviews, usually linked to the pressures of teaching in a challenging school context. Staff could describe the challenges associated with workload and meeting the diverse needs of pupils, including those new to the country or to formal education. Reflective practice was used by participants as a way of reframing these challenges as opportunities for growth and development. For teachers with fewer years of experience, it offered a sense of reassurance and supported the shaping of their professional identity, and for those with more experience or holding leadership roles, it provided space in which to think and then support others.

Change

Change was another key theme. The school’s rapid improvement journey had brought with it many changes – to leadership, staffing, systems and approaches. The participants were able to reflect on the need to adapt, and found reflective practices a useful way of making sense of new expectations or highlighting the key mechanisms of pedagogy and systems that remained in place.

Choice

The theme of choice captured the participants’ sense of agency and autonomy. Reflective opportunities allowed staff to consider decisions in classroom practice (either their own or across that of their teams) and their interactions with colleagues. Most frequently, participants spoke about their use of reflection to consider available options and align their actions and approaches with their professional values, before deciding on the best course of action. This meant that reflection shaped the retrospective learning of participants and also informed their judgement when moving forward.

Conflict

Across all the data, and when considering these emergent themes, conflict appeared as a unifying thread. Participants continually reported turning to reflection when faced with events or incidents that could be described as ‘negative’. These included interpersonal difficulties or challenging dynamics within teams, and competing demands or tensions between personal and professional priorities and values. In this manner, reflection functioned both as a coping mechanism and as a strategy for resolving a range of scenarios. The prominence of conflict within the data gathered suggests that, for all participants in this project, reflection was used most powerfully within moments of tension, where competing values and perspectives must be considered before finding a suitable solution.

CPD design

The reflective CPD design, which flexed to meet the needs of the staffing team, also provided scope for all participants to take something tangible from each session. The autonomy built into the design of the overall project allowed each person to take something different from the sessions and apply it to their own practice in a manner that was meaningful to them. This suggests that reflective practice, when built into CPD, does not need to prescribe uniform outcomes or success criteria, instead offering a flexible framework that allows staff to identify learning that resonates professionally and personally (Sellars, 2017).

A final notable finding related to the data – or lack thereof – from the written reflections. This opportunity to reflect in writing of any form or style was set as a gap task between sessions for participants. Despite the positive response from all staff who engaged in the CPD sessions, and from the participants themselves, there was a distinct lack of written reflection completed as a part of this project. Interviews suggested that staff preferred to reflect verbally, either individually (often on the commute to or from school) or with colleagues, when an event provided a need to reflect. This lack of engagement with the reflective writing could raise a question about whether the requirement to ‘produce’ something in a written form acted as a barrier, making reflection feel like an additional task or a greater workload, rather than a natural process and useful tool.

This leads to a wider consideration within professional learning: should reflection be formally captured or does this expectation have the potential to diminish the value that it creates? Written summaries may support accountability, but at the same time they risk constraining the openness of effective reflection. A more flexible approach, continuing to offer autonomy and authenticity, is likely to respect the realities of teaching and teacher workload while still fostering professional growth.

In summary, the findings and emergent themes highlight the complexity of engaging in reflective practices in a demanding school environment. Challenge, change and choice were central to the experiences reported by the participants, and it was in moments of conflict that reflection was most meaningfully enacted. Embedding this practice within the CPD provision created the space for staff to derive their own personal value from the shared professional learning. Despite this, the limited engagement in written reflections invites a further consideration of how to design reflective routines – and the time and spaces for staff to engage in them – to balance authenticity and accountability.

Conclusion

The research findings have prompted a consideration of several crucial discussion points relating to the place and value of reflection in primary schools.

Evolution

The first concerns the evolution of reflective practice over the course of a career and how professionals might be effectively supported as their need for and preferred means of reflecting changes over time. While reflection is fairly well integrated with the training and induction of new teachers, there exists a lack of structured opportunities to engage with reflective practice in the later stages of a teaching career. Our findings emphasise that the autonomy and ability for individuals to choose from a range of strategies at appropriate times affirms the importance of ongoing engagement with the skill of reflection. Indeed, Sellars (2017) describes reflection as a way of being rather than a task to complete, which further strengthens the argument for continuous consideration of how this fits into the culture of a school to support all staff in making reflective practice a core part of their professional life and learning.

Investment

The second calls for a consideration of the dichotomy of staff investment and investment in staff. In summary, ongoing commitment to the development of staff and the subsequent investment of individuals in their own professional learning should be viewed as complementary forces that drive educational improvement (Kennedy, 2016). When schools provide the time and resources for CPD, they are more likely to foster a culture where staff feel valued and motivated to refine their practice. Equally, when staff actively invest in their own professional growth, they offer new perspectives and increased enthusiasm, which directly influence teaching and learning. It could therefore be argued that this reciprocal investment in reflection ensures that education remains dynamic and responsive to the evolving needs of both teachers and learners.

Value

Equally important is the shared perception of reflective practice as a valuable component of professional growth. For teachers, reflective practice can be seen as a means of developing greater self-awareness, refining specific teaching strategies and deepening their sense of professional identity. For school leaders, it can lead to a thoughtful, adaptive workforce committed to continual improvement in response to both shared and individual goals. When staff and leaders recognise the value of reflection, it shifts from being a routine requirement and becomes a meaningful process. This enables dialogue and collaboration, resulting in innovation and collective responsibility for improving professional practice (Sellars, 2017).

Leadership

For reflective practice to become embedded within a school’s culture, leaders must actively model it for their teams. When leaders openly engage in reflective practices, they demonstrate humility, transparency and a willingness to continuously learn. This not only stands to legitimise reflection as a professional expectation but also encourages staff to engage with it authentically rather than superficially. By creating safe spaces for reflection, engaging in reflective dialogue and acting visibly on the outcomes of their own reflective process, leaders nurture a collaborative and improvement-focused environment. In doing so, they embody the belief that reflective practice is not an optional add-on, but rather an integral part of effective leadership and professional learning.

Protected space

Finally, for reflective practice to become genuinely impactful, schools must provide designated space and time within the working day for it to take place. Without this structural commitment from leadership, reflective practice risks being pushed aside by the more immediate pressures of teaching and administration (Bolton and Delderfield, 2018). By protecting regular opportunities for staff to pause and share insights, leaders affirm that reflection is not a ‘nice-to-have’ but a professional necessity, and in a sense give staff permission to take this time for themselves. This commitment from leaders not only strengthens individual practice but also cultivates a culture of collective learning, ensuring that continuous and meaningful improvement remains embedded in the daily life of the school.