Naheeda Maharasingam, Headteacher, Rathfern Primary School, UK

In September 2015, the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were formally adopted at the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Summit. The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs provide a comprehensive vision and framework for all populations across the globe. As goals for all people of our planet, they require teachers and pupils to develop a deeper understanding of how social action is pivotal to sustaining our planet for all its people.

As an educator of over 25 years, developing a curriculum underpinned by the goals of social and environmental justice at times feels utopian but nevertheless compelling. At Rathfern Primary School, these goals drive our curriculum intent, shaping our culture, curriculum and pedagogy. Our approach to developing social action enables teachers and pupils to imagine (envision) a better future for all through learning about SDGs.

Developing an awareness of the dilemmas and challenges of sustainable development necessitates the interruption and interrogation of our assumptions and long-held values. The school’s pedagogy develops critical thinking and attempts to interrupt our usual thinking and help to reframe it towards sustainable living. Biesta’s call to educators ‘to open up literal and metaphorical spaces where the child or student can establish a relationship with their desires’ (2017, p. 18), which can often be unsustainable, is apt here. Our pedagogy and school culture facilitate reflection for action in a safe space.

Envisioning

The SDGs (there are 17) promote ‘envisioning’ – pupils and teachers being able to imagine a better future. The premise is that when we know where we want to go, we will be better able to work out how to get there. Envisioning enables us to establish an ongoing link between long-term goals (SDGs) and our immediate actions. This is an ongoing process that develops collaborative tasks for pupils and teachers, developed through school assemblies and curriculum planning.

The commitment of our learning community to social action is driven by moral purpose,

which is, in part, an acknowledgement, recognition and identification of ‘habitus’, which perpetuates inequality in our society and across the globe. We imagine a better future framed by the SDGs, which promote social and environmental justice for all people of the planet. Understanding the SDGs through a local, national and global approach enables our pupils to connect tangibly with inequalities such as food poverty (SDG 2: Zero hunger). Our pupils have been inspired to set up and run our own school food bank. This is social action that addresses SDG 2 at a local level.

Educating

We practise an iterative approach to embedding the SDGs. This iterative approach creates the space to reflect and adapt the curriculum in order to forge stronger links to examine social and environmental justice issues.

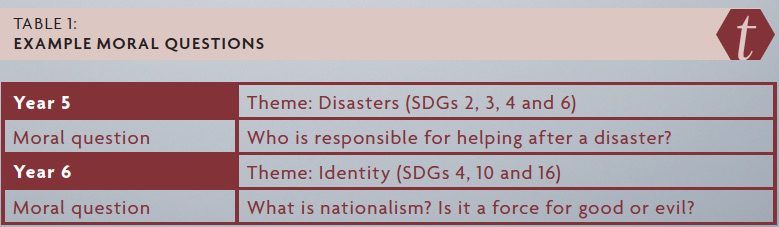

SDGs are woven into the curriculum themes, enabling links to be made – for example, the Year 5 theme of ‘Disasters’ is linked to SDG 2 (Zero hunger), 3 (Good heath and well-being), 4 (Quality education) and 6 (Clean water and sanitation). We provide our children with a broad, balanced and experiential curriculum where they are encouraged to develop critical thinking skills, enabling them to critically consider questions of social justice, inequality and environmental integrity.

Our approach supports the shaping of individual and collective knowledge, skills, values and attitudes, to enable our learning community to move along pathways towards sustainable development and become a catalyst for development itself. This progressively equips our learners with the knowledge, skills, values and attitudes needed to be responsible global citizens.

Interrupting

SDGs, as curriculum drivers, contribute to what Biesta describes as the key educational challenge: ‘not simply to tell the child which of their desires is desirable but for this question to become a living question in the life of the child’ (2019, p. 60). For example, in a theme such as ‘Disasters’, where pupils engage with SDG 2 (Zero hunger), looking at how communities address hunger during a disaster, pupils examine what hunger means and what their responsibilities as global citizens are, linked to SDG 2. Pupils examining SDGs learn to question their beliefs, for example around the difference between feeling hungry and experiencing hunger. This example of reframing what hunger is is what Spivak refers to as the ‘uncoercive rearrangement of desires’ (2004, p. 526).

All curriculum themes linked to SDGs have key moral questions for pupils to consider and discuss (Table 1). These are refined and reframed across the curriculum, enabling teachers to interrupt children’s thinking in a safe space and promote the development of critical thinking by:

- providing new perspectives

- promoting alternative ways of thinking

- developing metacognitive awareness.

Table 1: Example moral questions

Critical thinking enables children to learn to explore economic, environmental, social and cultural issues in the context of sustainable development, and challenges them to examine and question the underlying assumptions that influence their world views by reflecting upon unsustainable practices, e.g. SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production. Critical thinking leads to confidence in addressing the dilemmas and challenges of sustainable development.

Social action

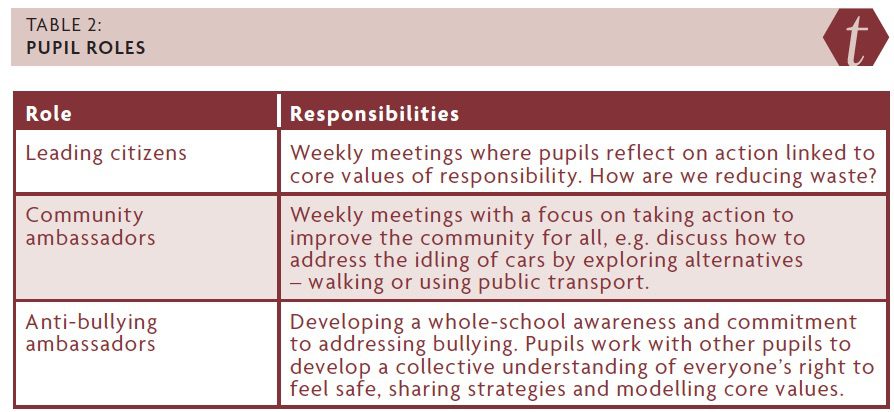

Teacher and pupil leadership is fundamental to driving and embedding the SDGs. This cumulative approach builds pupil and staff motivation to take meaningful action by harnessing their passion to achieve the SDGs. Pupil participation in decision-making is integral – empowering oneself and others. This means children being involved in joint evaluation, planning and control of local decisions. Pupils are democratically elected for a number of roles (Table 2). All pupils are engaged in a local project once a year to improve the local environment, such as litter picking in a park, along the River Quaggy or along the school road; planting trees; creating a community garden; saving water by not running a tap; and anti-idling campaigns.

Table 2: Pupil roles

Conclusion

Through envisioning, educating and interrupting, we aim to develop a community committed to social action. We are nurturing and bolstering the motivation pivotal to learning to live within the environmental limits of our planet and to build a just, equitable and peaceful society (UNESCO, 2013). The SDGs enable our pupils and teachers to envision equity for all people and the protection of our planet, guaranteeing its longevity for the future of all. SDGs as curriculum drivers imbue our pupils with, above all, a sense of purpose and hope for their future.

As a headteacher of a learning community committed to social and environmental justice, I am inspired by both pupils and teachers alike in their dedication and determination for social action. The leadership challenge is to maintain our focus on what we think matters in education.

DefinitionsSustainability is learning to live within the environmental limits of our planet and to build a just, equitable and peaceful society (UNESCO, 2013). Social action is ‘practical action in the service of others to create positive change’ (Le Breton, 2018, para. 2) or taking action to address social or environmental issues affecting our communities (local or global). Habitus is ‘the way society becomes deposited in persons in the form of lasting dispositions, or trained capacities and structured propensities to think, feel and act in determinant ways, which then guide them’ (Wacquant, 2005, p. 316, cited in Navarro, 2006, p. 16). Critical thinking is ‘seeing both sides of an issue, being open to new evidence that disconfirms your ideas, reasoning dispassionately, demanding that claims be backed by evidence, deducing and inferring conclusions from available facts, solving problems, and so forth’ (Willingham, 2007, p. 8). |

References

Biesta G (2017) The Rediscovery of Teaching. New York and London: Routledge.

Biesta G (2019) What is the educational task? Arousing the desire for wanting to exist in the world in a grown-up way. Pedagogía y Saberes 50: 51–61.

Le Breton R (2018) 8 ways to improve social action in your primary school. In: Young Citizens. Available at: www.youngcitizens.org/blog/8-ways-to-improve-social-action-in-your-primary-school (accessed 4 August 2020).

Navarro Z (2006) In search of cultural interpretation of power. IDS Bulletin 37(6): 11–22.

Spivak G (2004) Righting the wrongs. South Atlantic Quarterly 103(2/3): 523–581.

UNESCO (2013) Learning to Live Together: Education for Conflict Resolution, Responsible Citizenship, Human Rights and Humanitarian Norms. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/interculturaldialogue/resources/102 (accessed 22 October 2020).

United Nations (2015) About the Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals (accessed 4 August 2020).

Willingham DT (2007) Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Educator 31: 8–19.