Instructional Strategies for pupils with Speech, Language and Communication Needs

In 2012, Barack Rosenshine published the Principles of Instruction: a set of 10 research-based principles of instruction, along with suggestions for classroom practice. The principles come from three sources: (a) research in cognitive scienceThe study of the human mind, such as the processes of though, (b) research on master teachers, and (c) research on cognitive supports.

The 10 Principles of Instruction are as follows:

- Principle 1: Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning: Daily review can strengthen previous learning and can lead to fluent recall.

- Principle 2. Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step. Only present small amounts of new material at any time, and then assist students as they practice this material.

- Principle 3. Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students: Questions help students practice new information and connect new material to their prior learning.

- Principle 4. Provide models: Providing students with models and worked examples can help them learn to solve problems faster.

- Principle 5. Guide student practice: Successful teachers spend more time guiding students’ practice of new material.

- Principle 6. Check for student understanding: Checking for student understanding at each point can help students learn the material with fewer errors.

- Principle 7. Obtain a high success rate: It is important for students to achieve a high success rate during classroom instruction.

- Principle 8. Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks: The teacher provides students with

temporary supports and scaffolds to assist them when they learn difficult tasks. - Principle 9. Require and monitor independent practice: Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic.

- Principle 10. Engage students in weekly and monthly review: Students need to be involved in extensive practice in order to develop well-connected and automatic knowledge.

This content was originally produced as part of the Accelerate programme, a Department for Education-funded early career teacher programme designed and delivered by Education Development Trust with the Chartered College of Teaching. It is used here with kind permission of Education Development Trust.

‘Every teacher is a teacher of SEN’ (Code of practice 2015)

With numbers of young people identified as having a special educational need continuing to rise, perhaps never before has the above statement been so important.

Recently published census data shows there are over 1.3 million students with SEN nationally which equates to 14.9% of young people in our education system. This blog focuses on the almost 300,000 students who are identified as having speech, language and communication difficulties in the broad areas of need, and will explore Rosenshine’s principles of instruction through a SEND lens, looking at practical strategies and proven approaches to support students with their learning.

The Royal College of Speech & Language Therapists (2018) describes the significant impact a communication/language disorder can have on a child engaging with all aspects of school life and reaching their full potential. Students with a speech/language and communication disorder are more likely to struggle accessing a formal academic curriculum, and may also find themselves isolated and challenged by the social aspect of school life.

Students having a voice and being able to communicate their needs and express themselves are key foundations of any successful class environment. As practitioners it is essential we support our students with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) and respond to what can be highly personalised and bespoke forms of communication.

Personalised communication methods including Makaton, personalised signs, PECS and a range of symbols and visual supports are commonplace in specialist and many mainstream classrooms. The classroom environment can be a great support to students who have SLCN in terms of their learning, confidence and ability to function and learn independently.

The iCommunicatetherapy website outlines how we might create a total communication environment by using different forms of communication together (verbal, signing, symbols and visual support) to support communication, interaction and learning.

In my experience, this approach has a positive impact for all students – and even students who weren’t identified as having a SLCN not only enjoyed, but benefitted from the approach, making accelerated progress.

Below are some examples of a ‘Total Communication’ environment to support learning:

Many students are very aware that they may be communicating in a different way to some of their peers and will feel anxieties around this, particularly in a mainstream setting.

There are some great examples of how schools have used age-appropriate, more subtle communication aids such as personalised communication key rings which allow students to express themselves and communicate effectively whilst not being marked as different to their peers.

Technology continues to develop, and augmentative and alternative communication devices such as tablet devices now have advanced software that support non-verbal students in communicating their needs effectively and allow them to access learning across the curriculum. An inspiring example of inclusive communication was ‘non verbal’ students at Bennerley Fields Specialist Speech & Language College taking the role of main characters with speaking parts in the Christmas production using Makaton and AAC alongside their co-stars.

Questioning is a key feature of Rosenshine’s principles of instruction and is of particular significance when working with students who have speech, language and communication difficulties.

Cotton (1988) suggest that students go through a number of steps when faced with a question with this process being significantly more complex when a student has impaired communication skills.

The very first stage of attending to a question can be extremely challenging for a young person with limited receptive language skills. All too often as professionals we give very little processing time which is often essential for students with additional needs as they will need time to break down the question and think things through before being able to formulate an answer and response.

Cotton (1988) discovered that the average wait time given following a question was 1 second. Follow up research completed by Lemov (2015) found that almost 30 years later the wait time……..remained the same! The speed of questioning can be very damaging for SLCN students with increased anxiety, poor self-esteem and, in some cases, the learners may withdraw and completely switch off to the activity and desired learning outcomes.

As teachers there are a number of strategies we can use to combat this. The most obvious approach is of course to give more processing time… a great tip for this would be to use Iris Connect to record yourself and reflect on wait times – which will almost always be shorter than we feel in real time such is our human nature to want to ‘fill’ silence.

A great strategy is to present students with SLCN with questions – either in written form or with visual supports – slightly earlier than their peers. Not only does this allow for longer processing time, it also helps create a more inclusive environment with students accessing the same learning opportunities as their peers. A common issue is teachers and support staff using too much language and overloading students with information. In previous Accelerate materials we have explored Cognitive Load TheoryAbbreviated to CLT, the idea that working memory is limited and it is important to recognise that for students with SLCN, excessive use of often superfluous language can maximise their extraneous load.

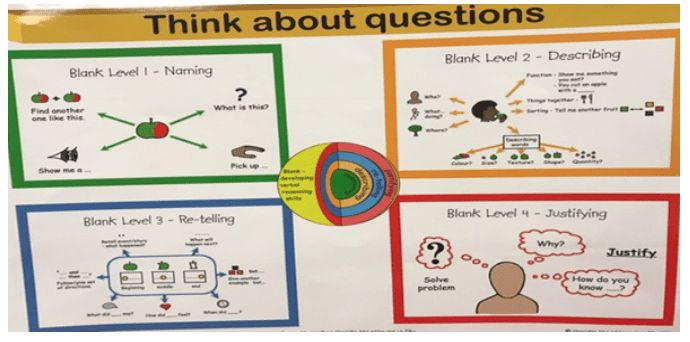

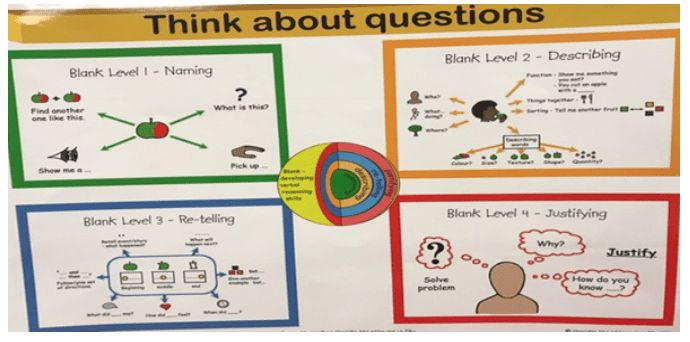

Blank, Rose and Berlin (1978) created ‘The Blank Model’, which outlines four different levels of questions and helps support and further develop a child’s understanding of abstract language and verbal reasoning.

The four levels are described below:

Level 1: Naming (language demands rely on teaching materials e.g. objects/pictures)

Level 2: Describing (language relates to teaching materials e.g. objects/pictures)

Level 3: Re-telling (language has less emphasis on the teaching materials)

Level 4: Justifying and Problem Solving (language is more advanced than the teaching materials)

Adopting a culture of blank level questioning in our classrooms can have a significant impact on participation and inclusionAn approach where a school aims to ensure that all children. Asking the ‘right questions’ helps us to make learning more accessible and also identify misconceptions students may have. Having ‘blank’ posters on display act as great prompts for teachers and support staff whilst many students enjoy visually seeing themselves progress through the levels.

A key skill many colleagues working in specialist education have is the ability to break broad concepts down into manageable, bitesize chunks.

Rosenshine describes how the most effective teachers take care not to overload students with too much new information and offer lots of support and opportunities to practice as we look to embed learning.

Using only key language, ensuring there is plenty of processing time, and even something as simple as saying a students name and then pausing before asking a question, can make learning and lessons more accessible.

‘Our working memory, the place where we process information, is small. It can only handle a few bits of information at once – too much information swamps our working memory. Presenting too much material at once may confuse students because their working memory will be unable to process it.’ (Rosenshine 2012, p.13)

Students with additional needs are quite commonly ‘over supported’ and some will go through school with a ‘Velcro TA’ never far from their side. Adults regularly answering questions for students with SLCN is a prime example of this and can take away from a young person’s dignity and self esteem. A challenge for us as professionals when working with students who have additional needs, is to support them in achieving aspirational levels of independence and being able to function successfully in school and the wider community.

Rosenshine describes the effectiveness of scaffoldingProgressively introducing students to new concepts to suppor and how worked examples and non examples can support and enhance a student’s learning and knowledge base. The use of knowledge organisers, and in particular graphic organisers- in which additional information and visual supports can be easily added or taken away – can provide SLCN students with key information, vocab and importantly, a solid foundation to further explore a topic area or content independently.

- Social stories can be a fantastic way to introduce new and potentially challenging learning to students. The careful selection and repetitive nature of the language is proven to support processing and understanding.

- Comic strip conversations work well for students who may think that social stories are a bit ‘young’ for them. For more about social stories and comic strip conversations, take a look at the social stories section of the National Autistic Society website.

Many students will take social stories or comic strips home with them and regularly refer back to them. These again support the notion of ‘faded guidance’ and help our students to be less reliant on adult support.

‘Fading is the moment in which you are present but get to step back and watch pupils take their first flight. It’s a thrilling moment in teaching.’ (Cullen 2019)

Using instructional strategies successfully has long been a feature of a good teacher supporting students with additional needs. Strategies around retrieval and the use of scaffolding and faded guidance are regularly found in the SEND classroom and in many ways our specialist colleagues lead the way when it comes to breaking down tasks into smaller steps. Considering the use of instructional strategies and building opportunities to use them is useful to have in mind as we plan and structure sequences of lessons with the very best teachers looking for connectivity and links between subject and content.

The use of a ‘spiral curriculum’ approach to learning as defined by Harden (2009) is particularly effective in the way it ensures students experience regular practice that supports them in building well-developed, more complex schema that can be applied successfully to other areas of learning.

Having a number of tried and tested instructional strategies can have a really positive impact on our skills as a teacher and more often than not lead to improved results in the classroom. Retrieval activities, questioning strategies, interleavingAn approach to learning where, rather than focusing on one p and spacing all covered in the Module 3 workshops can all be woven into everyday practice and help to create a great climate for learning.

Whilst the research aligns closely with classroom practice, there are still significant gaps when it comes to SEND-specific research, which is potentially an opportunity for colleagues to consider as they move through the Accelerate Programme – you may like to take the opportunity to collaborate, set up mini projects and engage with your community of practice to explore this further.

Twitter recommendations for SEND AND SLCN

References

Blank M, Rose S A and Berlin L J (1978) The Language of Learning. New York: Grun & Stratton.

Cullen S (2019) Fading: removing teacher presence in directed teaching. In Boxer (2019) The ResearchEd guide to explicit and direct instructionA method of instruction in which concepts or skills are taug. Woodbridge: John Catt.

Cotton K (1988) Classroom Questioning: Office of Educational Research & Improvement (OERI) New Jersey, US: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory.

Department For EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s serv (2019) Special Educational Needs in England 2019 – January Census. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/814244/SEN_2019_Text.docx.pdf (accessed 16 December 2020).

Department For Education (2015), Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/398815/SEND_Code_of_Practice_January_2015.pdf (accessed 16 December 2020).

Harden R M (2009), What is a Spiral Curriculum. Medical Teacher Journal 21(1): 141-142.

Lemov D (2015) Teach Like A Champion 2.0: 62 techniques that put students on the path to college. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass.

Rosenshine B (2012) Principles of Instruction: Research-Based Strategies That All Teachers Should Know. American Educator 36(1): 12 – 39. Available at: https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Rosenshine.pdf (accessed 16 December 2020).

View the Principles of Instruction research paper

Return to the Principles of Instruction collection