SHALINI BHORKAR, ROBERT CAMPBELL AND JULIETTE CLARO, ST MARY’S UNIVERSITY, TWICKENHAM, UK

Teacher recruitment and retention remain ongoing challenges in England (Maisuria et al., 2023). Most notably, recruitment of modern foreign language (MFL) and physics trainee teachers is particularly stark (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2025a). To address under-recruitment in these subjects, government bursaries are now available to international candidates. These bursaries expand historic recruitment from Europe to include people from the Global South, leading to a considerable increase in the number of international trainee teachers in England (DfE, 2025a). The growth in the number of international preservice teachers (IPSTs) and in ethnic diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences has prompted us to initiate reflective discussions on how teachers, mentors and school leaders can work collaboratively with initial teacher education (ITE) providers to ensure that we model inclusive practice that supports international trainees to thrive. These reflective discussions aim to challenge and provide an alternative to the deficit narratives often perpetuated by the current anti-immigration political climate, and instead celebrate the rich experience and expertise that international trainee teachers bring to the classroom. This paper summarises our efforts to adopt an inclusive approach in our practice, highlighting the challenges of providing truly inclusive, decolonised teacher education. It calls for stronger, nationally standardised systems that support international trainees as they navigate a rigid framework and a fast-paced education system.

This perspective paper uses initial findings from ongoing research to examine how our practice as initial teacher educators supports IPSTs to acclimatise to the English school education system. The IPSTs that we discuss in this piece are studying either the secondary PGCE in MFL with qualified teacher status (QTS) or the PGCE science with physics specialism QTS course at St Mary’s University. These findings demonstrate that, despite our extensive revisions to our curriculum offer and efforts to adopt inclusive practice through our work as teacher educators, systemic barriers continue to inhibit the prospects of IPSTs.

Anticipating barriers to integration pre-arrival

Contrary to other countries, such as New Zealand (Education Workforce, 2025) and Canada (Pathways to Teach Canada, 2025), where governments provide pre-departure programmes, in England the responsibility of supporting international trainees to settle and integrate within the education system rests solely with the ITE providers. Among other questions linked with consistency and quality of provision across different providers, IPSTs are often thrown in the deep end without a coherent national programme to integrate them pre-departure. Systemic barriers include understanding English curricula, exam specifications and protocols for safeguarding and behaviour management, as well as navigating differences in culture and perceptions that are not integrated or valued in their school setting (Claro, 2026; Tereshchenko et al., 2023). Other systemic barriers include the concept of colonialingualism (Meighan, 2022), which refers to the overt and covert privileging of colonial languages, and the perception that alternative English accents may not be acceptable in the classroom (Cushing and Clayton, 2024).

Constructing a working group to support IPSTs

To address the absence of a national programme supporting IPSTs in navigating a move to England, our working group, comprising teacher educators, the international recruitment team and visa specialists, supports IPSTs from the point of application through to the completion of their ITE course. Through a meeting every six weeks, this working group created space and time for dynamic responses to challenges in integrating international trainee teachers.

Impact of our international group

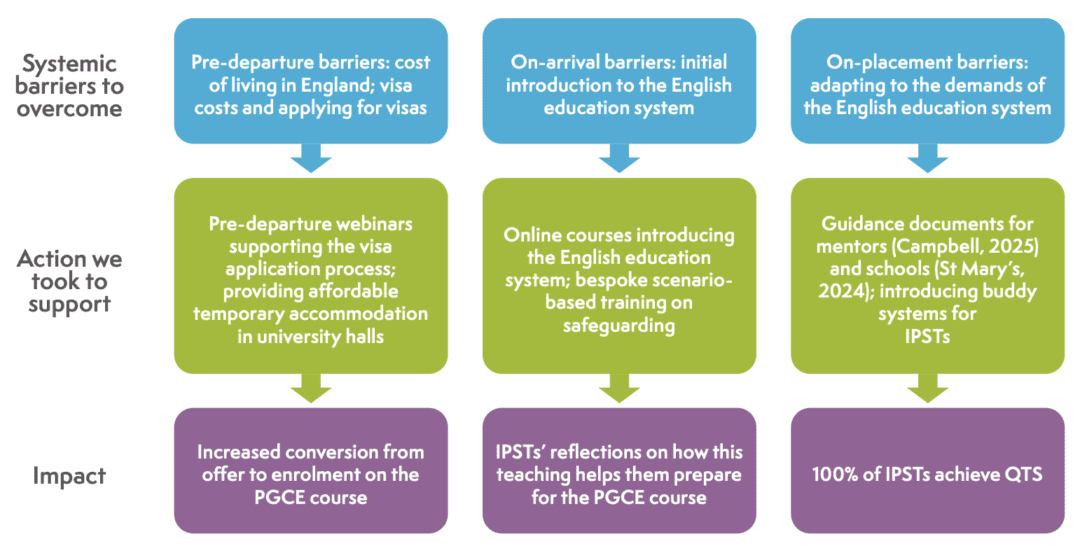

The international group has made several revisions to the onboarding process for international candidates. These revisions began once an international candidate attended an interview and are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A flow diagram showing our ongoing actions to respond to the systemic barriers faced by international preservice teachers

This flow diagram provides an overview of the actions that we took at each stage to support IPSTs. Next, we briefly discuss our sustained support once IPSTs start their teacher education course, before examining the challenges in living our inclusive practices in our work as teacher educators.

In-course support

The in-course support involves a two-pronged approach. First, our pastoral support led us to introduce a buddy system with bi-monthly lunches. Our work with the local church community introduced the first international carol service, with local churches also hosting IPSTs who were unable to return home for the Christmas holidays. Second, as teacher educators, we were keen to examine how we adapt our practice to meet the emergent needs of IPSTs (Campbell et al., 2026). One example was a review of physics teaching, which initially assumed that teachers from the Global South may be less familiar with practical work or group-based activities. Opportunities to critically examine assumptions revealed how deficit views of international trainees were often unfounded. Shifting to a student-centred approach, where trainees shared how they might teach physics topics, not only challenged these assumptions but also highlighted trainees’ valuable expertise. Engaging with their diverse experiences enabled teacher educators to reflect on and refine their own pedagogical practice.

Challenges in living out our practice

Initially, our efforts to adopt an inclusive and welcoming stance towards IPSTs did not immediately inform all our actions as teacher educators. One pertinent example is the approach to recruiting IPSTs to the PGCE physics course. Since the introduction of the international bursary for physics, the number of applications to the PGCE physics course has increased tenfold. Initially, our revisions to the recruitment process were based on staff workload, ensuring that we could handle a significant increase in applications effectively and efficiently. We set up an additional group interview for international candidates. These initial interviews could accommodate up to 10 candidates in a single 40-minute interview slot, assessing their subject knowledge and literacy skills. These assessment points were used as shortlisting criteria for subsequent one-to-one interviews. Those who were shortlisted were then asked to exemplify their pedagogical skillset as teachers. By comparison, home applicants had a single one-to-one interview that included all the aforementioned tasks. Initially, we were blinded to how this disparity in the interview process diminished our inclusivity and perpetuated ill-informed stereotypes about pedagogical approaches between international and home-based preservice teachers. It was only through our collaborative efforts with fellow teacher educators, who were also researching how the growth of IPSTs informed and revised their practice – discussed elsewhere in the online version of this issue (Campbell et al., 2026) – that the injustice in our approach to recruitment became evident.

We have now further revised our recruitment approach, using innovative software to ensure that international candidates can highlight their skills and what they offer in the recruitment process. These online resources enable all candidates, regardless of nationality, to upload audio clips and video responses to exemplar scenarios, thereby illuminating the pedagogical skills that they can bring to the teaching profession. Although we still include subject knowledge and literacy tasks, they are not automatically used as shortlisting criteria, allowing all candidates, irrespective of nationality, to highlight their skills without prejudice

Addressing microaggressions during school placements

In addition to efforts to revise our teaching on the PGCE course, we also recognised a need to tailor the support that we offer to school partners who host IPSTs on school placements. The support was initially targeted at mentor training. This training was informed by existing research suggesting that unconscious bias disproportionately affects minority ethnic teachers (Panford, 2025). Drawing on intercultural communication principles (Rosinski, 2003; Iqbal, 2021; Claro, 2026), this culturally sensitive training responded to evidence of racial microaggressions in ITE programmes (Tereshchenko et al., 2023) and aimed to foster a reflective, responsive environment for international trainees, promoting adaptability and empathy among mentors and ultimately promoting a culture that supported both professional growth and inclusivity.

Yet ongoing conversations with school partners suggest that the high workload and pressure on outcomes threaten the potential gains from tailored mentor training. Currently, mentors are allocated 90 minutes per week to support trainees (DfE, 2025b). Although effectively supporting any preservice teacher – irrespective of nationality – within this timescale can be challenging, it is insufficient to navigate cultural change alongside the demands of supporting IPSTs to reflexively consider how they apply their prior teaching experience to the English curriculum. The lack of time available to mentors can inhibit their ability to embody cultural sensitivity, which in turn can be perceived by IPSTs as microaggressions and as an unwillingness to consider alternative pedagogical approaches.

Concluding comments

We have provided examples of how we used evidence-informed practice to revise our teaching to cater for an increasingly diverse cohort of preservice teachers. These revisions included introducing new modules to support IPSTs in familiarising themselves with the English education system and navigating a complex immigration system. Yet we have also shown that living out cultural sensitivity in daily practice is challenging. Moreover, acknowledging how lived practice fails to embody cultural sensitivity requires humility and courage. Nonetheless, this perspective piece provides some preliminary steps to support fellow educators in practising cultural sensitivity and the reflexivityReflexivity draws attention to the researcher, rather than pretending that they they did not influence the research. It involves an examination of how the researcher's own beliefs, judgments and practices may have influenced the research. required to ensure that IPSTs are not only welcomed in the English education system but also supported to thrive.