NICOLE PONSFORD, DOCTORAL RESEARCHER, BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY, UK

Introduction

Teacher retention, wellbeing and leadership development remain pressing challenges for schools in the UK and beyond. While much attention has rightly focused on pupil outcomes, the professional experiences of teachers and school staff often remain underexplored in academic research and in practice. This is particularly true for colleagues whose identities are underrepresented in official datasets – including global majority staff, women, neurodivergent and disabled colleagues, and those with caring responsibilities.

National data highlights rising attrition, workload pressures and persistent underrepresentation in senior roles (Miller, 2020). Yet traditional workforce datasets do not routinely capture intersectional identity information (Crenshaw, 1989), meaning that many staff experiences remain invisible. This creates an intersectional evidence gap: leaders can observe outcomes but not the lived experiences that shape them. For example, national datasets such as the School Workforce Census do not record disability, neurodivergence or caring responsibilities in an intersectional way, limiting system-level understanding of staff experience.

This article draws on a multi-intervention action research project involving over 26,000 staff and students across 350 schools and five universities. It introduces Kaleidoscopic Data – a third-tier evidence approach created by the author through participatory action research (Ponsford, 2025a) that combines quantitative patterns with qualitative testimony to illuminate the lived, intersectional and relational experiences of staff. In doing so, it reframes equity as cultural and systemic, rather than transactional. In this article, equity refers to fair access to opportunities and resources, while inclusionAn approach where a school aims to ensure that all children are educated together, with support for those who require it to access the full curriculum and contribute to and participate in all aspects of school life focuses on the relational and cultural conditions that enable staff to feel a sense of belonging.

Kaleidoscopic Data enables leaders to see not only what is happening but also why – revealing the cultural and relational factors that influence equity, belonging and professional development.

Research background and methodology

The research involved co-created interventions with schools, teacher education providers and leadership networks. Staff experiences were gathered through surveys, focus groups and structured professional dialogues. Approximately 4,000 educators and students from across 21 schools and seven nurseries in the UK contributed to the dataset. Contributions from five universities were included to reflect experiences across the teacher development pipeline.

All data was collected as part of the project, rather than drawn from secondary sources. Participatory action research underpinned the design, with anonymity, agency and psychological safety prioritised. Participants could choose what to disclose, recognising that non-disclosure itself is meaningful data in contexts where identity is sensitive or stigmatised. The analysis followed an iterative process typical of participatory action research, where emerging themes were refined with participant input to ensure that findings remained grounded in lived experience. Full documentation of the methodological design and ethical considerations can be found in the author’s doctoral thesis (Ponsford, 2025a). An accessible summary of the wider dataset is available through the GEC (Global Equity Collective) research repository (Ponsford, 2025b).

Introducing Kaleidoscopic Data

Kaleidoscopic Data aims to address the intersectional data gap – the lack of layered identity insight within conventional workforce metrics. While first-tier data shows performance and second-tier data reveals patterns, Kaleidoscopic Data surfaces the ‘why’ – the social, cultural and relational mechanisms that drive inequity or belonging. In practical terms, Kaleidoscopic Data is collected by combining survey metrics with short qualitative prompts and ongoing staff voice activities, enabling leaders to understand both patterns and lived experiences.

This approach sits within the wider field of data-for-inclusion approaches – a commitment to collecting and using data ethically, with equity at the centre (D’Ignazio and Klein, 2023; Guyan, 2022). The analysis was informed by Woolcock’s (2001) and Bourdieu’s (2005) conceptions of social capital – the networks, trust and resources that individuals and groups can access. ‘Bonding capital’ captures relationships within identity groups; ‘bridging capital’ reflects relationships across groups; and ‘linking capital’ describes the influence that leaders hold to shape culture, opportunity and policy structures. In this study, social capital is evolved for educational leadership, illustrating how leaders can intentionally use linking capital to create environments that feel safe, fair and connected.

Findings: Hidden inequities in teacher development

The analysis revealed six key areas where staff experiences of exclusion were particularly pronounced. Across these themes, the intersectional data gap was evident: traditional metrics failed to capture the overlapping realities of gender, race, disability, caring responsibilities and role type. By applying data-for-inclusion approaches, these hidden inequities were made visible and actionable for leaders. Figure 1 summarises the six most significant equity gaps in teacher development, according to Kaleidoscopic Data.

Figure 1: Six most significant equity gaps in teacher development (Ponsford, 2025a)

While this article focuses on leadership action, classroom teachers can also use Kaleidoscopic Data principles by reflecting on belonging within their teams, noticing patterns of exclusion and initiating psychologically safe conversations with colleagues.

1. Flexible working and retention

Many staff described how rigid working patterns hindered both wellbeing and career progression. One participant commented: ‘I was told outright that if I wanted part-time hours, leadership wasn’t an option.’ Such practices disproportionately affect women, carers, and disabled and neurodivergent staff, contributing to attrition.

For leaders:

- Normalise flexible working in leadership roles and not just classroom positions

- Share examples of leaders and those aspiring to be leaders who work flexibly, to show that it is possible

- Use data-for-inclusion approaches to identify groups most disadvantaged by rigid models.

2. Non-disclosure and invisible identities

Many teachers and support staff choose not to disclose disabilities, neurodivergence or caring responsibilities. This silence often stems from fear of stigma, missed opportunities or even career penalties (Rabiger, 2023). When staff feel unable to share, schools cannot make the reasonable adjustments that would enable them to thrive. As one teacher explained, ‘It feels safer to stay silent than to ask for support.’ When leaders use linking capital to shape policy and model openness, schools can foster belonging that is contextually driven and staff-led.

For leaders:

- Build authentic psychological safety by showing staff that disclosure leads to support and not penalty

- Co-create processes with staff to make disclosure feel participant-led and not imposed

- Protect confidentiality and demonstrate through action that shared information is respected.

3. Career progression and leadership pipelines

Patterns of underrepresentation in senior roles were not simply about lack of aspiration but also about systemic barriers. Global majority and disabled staff reported fewer opportunities for mentoring and sponsorship, echoing Miller and Allen’s (2018) findings on the ‘liabilitisation’ of leaders from minoritised groups, where staff are ‘characterised as “incompetent”, “incapable” and “lacking good judgment”’ (p. 20).

For leaders:

- Audit promotion and mentoring systems with data-for-inclusion approaches to see who is being overlooked

- Offer coaching, bursaries and reverse mentoring to actively open doors for underrepresented colleagues

- Use bridging and linking capital to connect staff across groups and into leadership pathways.

4. Identity-based bias and belonging

Experiences of bias – both overt and subtle – were common. Staff spoke of being stereotyped, excluded from informal networks or feeling that they had to ‘code-switch’ to be accepted. Such experiences erode confidence and belonging, with direct implications for retention.

For leaders:

- Set explicit expectations that bias, harassment, discrimination and microaggressions will be challenged

- Create forums (identifiable and anonymous) for staff to share lived experiences safely, using data-for-inclusion approaches to identify themes

- Model inclusive leadership by demonstrating how linking capital can be used to connect staff voices to policy decisions.

5. Whole-staff visibility and representation

Students’ experiences of inclusion are not shaped solely by classroom teachers. They notice who welcomes them at reception, who supports them in the library, who supervises lunch, who runs pastoral support and who sits on leadership teams. When the wider staff body lacks diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences, students see a narrow picture of who belongs and who holds privilege in the school community.

For leaders:

- Audit not just teaching staff but the whole workforce through data-for-inclusion approaches

- Consider the ‘visibility effect’: who do students most often see and speak to, and what does this signal about belonging?

- Challenge assumptions that equity work belongs only in curriculum or pedagogy – it is about the lived experience of school culture in corridors, offices and playgrounds too.

6. Fluidity of staff lives and commitments

Staff circumstances are rarely static. Commitments to younger children, older dependents or new work roles often change across a career. Yet too often, leadership pathways assume a ‘linear’ model of progression that does not reflect lived realities. As one staff member shared, ‘I could have taken a leadership role five years ago, but my caring responsibilities grew overnight. There was no flexibility – so I stepped back.’

For leaders:

- Recognise that inclusion is about who could lead if pathways were more responsive to life changes

- Build in flexible entry and re-entry points to leadership programmes

- Use reverse mentoring and peer networks so that staff with caring roles can shape how leadership adapts.

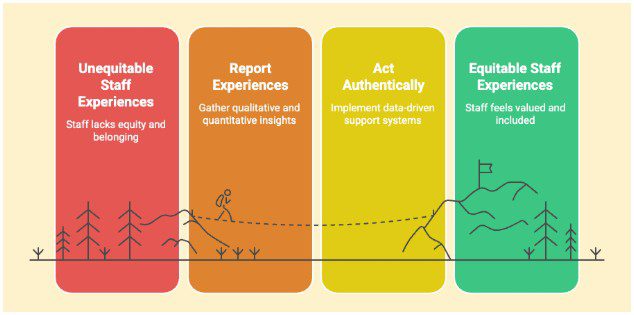

Implications for practice: A report and support model

The findings show that equity and belonging for staff cannot be left to chance or to one-off initiatives. Schools and trusts need approaches that combine better evidence with authentic action. A simple but powerful way in which to achieve this is through a report and support model. Figure 2 provides a visual overview of the report and support model used by schools in this study.

Figure 2: Report and support model (Ponsford, 2025a)

1. Report: Evidence lived experiences

- Use data-for-inclusion approaches to gather both qualitative and quantitative insights

- Audit the whole staff body – not only teaching staff – to understand who students see every day and where privilege is most visible

- Recognise the fluidity of staff lives and build this into planning

- Create feedback loops so that disclosure, bias and progression challenges are surfaced regularly.

2. Support: Act with authenticity

Collecting data is only the beginning. The real challenge is how leaders act on it in ways that staff trust and believe in.

- Provide coaching, bursaries and reverse mentoring shaped by lived experience and not just generic programmes

- Create authentic psychological safety by co-designing disclosure processes with staff

- Develop flexible career pathways that allow re-entry points into leadership

- Move beyond consultants who parachute in and leave – whole-organisational change must be owned by leaders and supported by learning from both internal staff voices and external expertise

- Establish a clear plan with feedback loops, so that inclusion is refined over time

- Ensure accessible, evidence-informed CPD (continuing professional development) that reaches across the entire workforce.

Conclusion

The challenge of equity in teacher development and leadership is both urgent and complex. Traditional metrics have left too many staff voices unheard, particularly those navigating the intersections of gender, race, neurodiversity, disability and caring responsibilities. By introducing Kaleidoscopic Data within a wider commitment to data for inclusion, this research offers a practical, ethical and participatory framework for surfacing these hidden realities. Coupled with a social capital lens, it shows how leaders can act locally – using their linking capital to create belonging within their own contexts, without waiting for national reform.