DOMINIC WYSE, PROFESSOR OF EARLY CHILDHOOD AND PRIMARY EDUCATION, UCL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION, UK; FOUNDING DIRECTOR, HELEN HAMLYN CENTRE FOR PEDAGOGY, UK

CHARLOTTE HACKING, RESEARCH AND CURRICULUM LEAD, HERNE HILL SCHOOL, UK; TEACHER ENGAGEMENT LEAD, HELEN HAMLYN CENTRE FOR PEDAGOGY, UK

The aim of this article is to describe a new theory of teaching, to reflect on engagement with this theory by teachers and policymakers, and to prompt those with an interest in education to think more explicitly and critically about using theory to inform teaching.

Effective teachers have an extraordinary amount of knowledge, much of which is not easily seen or understood by people who are not experts in education. A key area of this knowledge is pedagogy. One of the professional roles of teachers is to make decisions about which pedagogies to use for the classes that they teach. These decisions are informed by many factors, but the factor on which we focus in this article is theory – general ideas informed by research that guide educational actions.

An exploration of two prevalent theories related to reading

A vital aspect of early years, primary and secondary education is supporting pupils in learning to read and write. With regard to the English language, there are several theories of reading that have been influential, some of which have been accompanied by visual models summarising key aspects of the theory.

The ‘simple view of reading’ (SVR) (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) is one theory that has been influential. For example, an interpretation of the SVR was included in the appendix to ‘The independent review of the teaching of early reading’ undertaken by Jim Rose for the Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England and Skills in 2006. Since then, it has appeared in the Education Endowment Foundation’s ‘Improving literacy’ guidance (EEF, 2015) and, more recently, in the Department for Education’s reading framework (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2023).

The theory of the SVR is not really simple at all. Its visual representation is R = D X C, which means that reading equals the product of decoding and comprehension (Gough and Tunmer, 1986, p. 7). England’s National Curriculum programmes of study for reading reflect the model in the presence of two dimensions: ‘word reading’ and ‘comprehension’. As a result, this means that the SVR is a basis for teaching in most primary schools.

Also relatively well known in England is the researcher Hollis Scarborough’s (2001) ‘Reading Rope’. Similar to the SVR, the Reading Rope identifies some elements of language comprehension and word reading processes that are needed if children are to become skilled readers. The Reading Rope replaced the reference to the SVR in the 2017 update of the EEF’s ‘Improving literacy’ guidance (2015).

Both of these theories and accompanying models have more often been equated with approaches to teaching reading that strongly emphasise phonics teaching first and foremost, as has been seen in education policy in England. But a limitation with these theories and models is what they omit. They overlook the interconnected nature of reading and writing, and how both depend on understanding and using language for communication and meaning-making.

Crucially, both the SVR and the Reading Rope are informed by evidence of children with reading difficulties. If any model is to be used to support an approach to teaching reading, then it needs to be built on evidence of what is effective for both typically and non-typically developing readers.

A new theory: The double helix of reading and writing

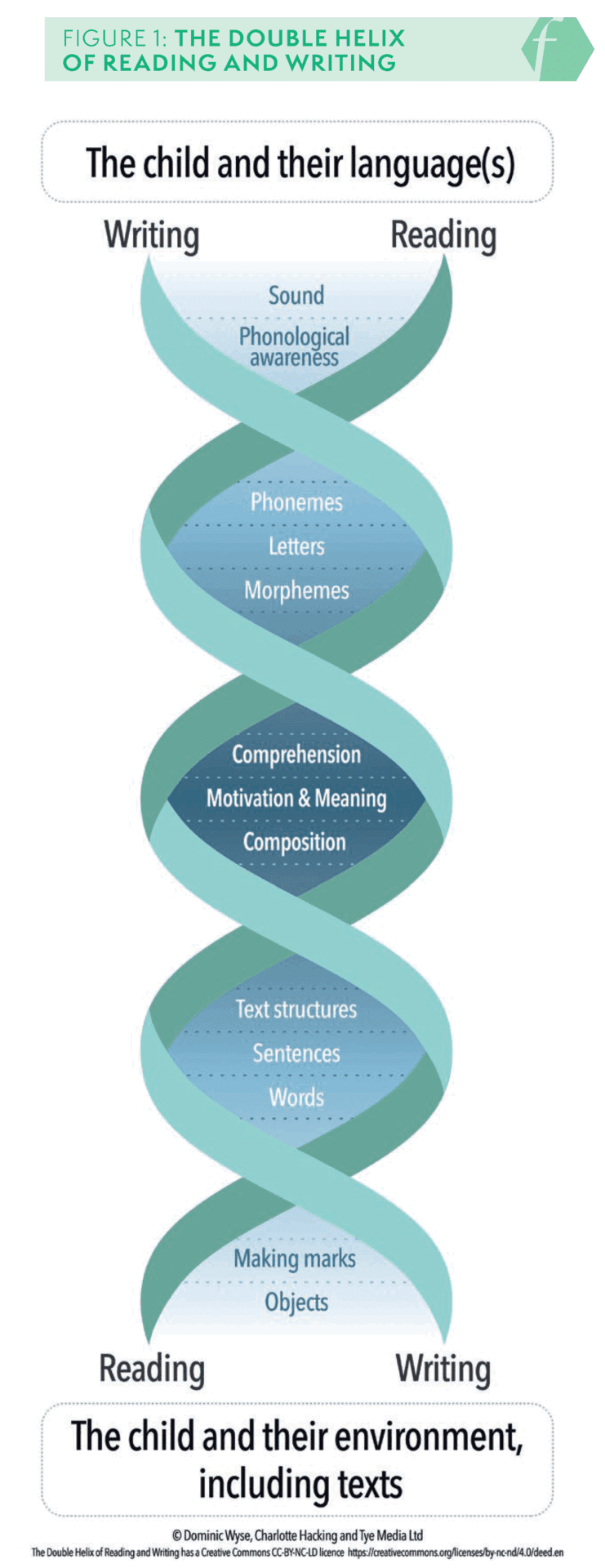

A new evidence-based theory of teaching reading and writing is the ‘double helix of reading and writing’ (DHRW) (Figure 1). The DHRW was created as the result of a series of research projects that are part of the Balancing Act initiative (UCL Institute of Education, nd), aiming to improve policy and practice in the teaching of reading and writing. More specifically, the theory and the visual image were created as a result of work carried out for a research paper (Wyse and Hacking, 2024a) and the book The Balancing Act: An Evidence-Based Approach to Teaching Phonics, Reading and Writing (Wyse and Hacking, 2024b), which detail the evidence base and the practices of teaching that inform and are informed by the DHRW.

Figure 1: The double helix of reading and writing

Unlike the SVR and the Reading Rope, the DHRW centres the interrelationship between language, reading and writing. It places the child, their language(s) and their environment at the heart, and emphasises the importance of motivation and meaning in children’s use of language, reading and writing. The visual model for the DHRW is based on a living phenomenon and the essence of life – the double helix shape that is part of human DNA. This is a deliberate reminder that using language, reading and writing is a uniquely human phenomenon. It includes the idea that all processes of oral and written language start to develop in embryonic and emergent forms as soon as children are born, based on the development of the brain, eyes, ears and limbs during the time prior to birth.

At the centre of the DHRW is the child – their language(s) and their environment, including texts encountered at home and at school. Key concepts in the model include:

- Motivation and meaning: Engagement with text begins with a search for meaning and the impetus to communicate

- Comprehension: This begins as oral language comprehension, and then develops as reading comprehension

- Composition: Writing involves constructing meaning through text

- Text structures and sentence-level understanding: Children learn how written language is formed and used for different purposes and audiences, through choices of words that are supported by knowledge about grammar, punctuation and text layout choices

- Phonological and phonemic awareness: This refers to an awareness of the sounds of language and, ultimately, the alphabetic code

- Morphemic knowledge: Understanding of meaningful parts of words, which also aids spelling and vocabulary development.

As children’s development of language, reading and writing is not a simple linear progression, the model allows for different emphases on different elements, depending on children’s development at any given stage of learning. These developmental aspects are a vital part of teachers’ knowledge, which links with teaching through their decisions on the most relevant interactions and activities for children at any given stage of a child’s development.

The theory and model necessitate a balanced approach to the teaching of phonics, reading and writing, in which the focus is first and foremost on the balance between teaching based on whole texts as models for language, reading and writing, and systematic teaching about the alphabetic code and other linguistic features. With this approach, the importance of comprehending and composing written language is carefully balanced with the acquisition of a range of skills and knowledge. Teaching makes explicit links between phonics teaching and other linguistic aspects, using real books as a priority. Reading scheme books with controlled vocabularies are used selectively if deemed to be useful. This differs from the synthetic phonics approach of most of the phonics schemes validated in England by the DfE, particularly in Reception and Year 1 classrooms. The balance allows teachers and children to experience the interconnected nature of language, reading and writing through teaching and learning.

Supporting teachers to choose and use theories

In England, with a review of the National Curriculum and assessment in progress, it is an apt time to look at how educators might be supported in selecting theories to inform effective teaching. Teachers, as professionals, should be the people who make decisions about pedagogy. Unduly prescriptive approaches by policymakers are less likely to result in optimal gains for pupils.

The signs from the interim report of the review of the National Curriculum (DfE, 2025) were that the current approach to synthetic phonics is unlikely to change, not least because the emphasis is replicated in the writing framework published in July 2025, a document that has already prompted hostility from some experts. The conclusions of the interim report came in the face of clear evidence of the need for some changes – for example, covered in responses to the review’s call for evidence from the Primary Umbrella Group (PUG), the United Kingdom Literacy Association, the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) and the Helen Hamlyn Centre for Pedagogy (HHCP). As a result of the current approach, not enough children have learned to read and write in the ways that they need to – something shown by statutory assessments in England (Wyse and Hacking, 2024b). Further, insufficient numbers of children are motivated by reading, as the surveys from the Progress in International Reading Literacy (PIRLS) suggest (Wyse, 2023).

A key question, then, is how might teachers and policymakers select one theory in favour of another? Fundamental to answering this question is that the theory must be a theory of teaching and not only a theory of learning. Unlike the DHRW, the SVR and the Reading Rope are theories of learning – the authors of the SVR made it clear in their original research paper that they were not commenting on teaching (Gough and Tunmer, 1986). The selection of a theory must also be one that is robustly evidence-based, which means that there should be, for example, peer-reviewed publications that clearly articulate how research has informed a particular theory.

Once a theory is selected to influence teaching, it is important that it is evaluated by teachers and by researchers. With regard to the DHRW, we have been heartened by the many organisations, schools, groups of schools and individual teachers, both nationally and internationally, who have contacted us about the new theory and model and how they are using this to develop teaching beyond a narrow approach to synthetic phonics. Teachers have been reading our work, discussing this at staff meetings, trying out the ideas and reflecting on the implications. There have been multiple engagements with policy developments as well – for example, with the Welsh Government Expert Panel on Literacy, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment in Ireland, the European Commission and literacy associations in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the UK and the USA.

Like any robust theory, the DHRW was subject to peer review. Prior to publication of the DHRW in our book, the theory was submitted to a journal as a research paper (Wyse and Hacking, 2024a). Following peer review, this research paper was published. Since then, it has won the ‘Wiley Research in Literacy Education Award’, providing further confidence in the robustness of the theory. The book was awarded ‘Highly Commended’ by the UKLA.

There is also the need for further evaluation through new research. In addition to the theory and research that underpins the DHRW, there are new research projects that will subject the theory to robust evaluation. One of the toughest tests will be the EEF-funded randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluation of CLPE’s ‘The Power of Reading’ (PoR) programme (EEF, nd). This iteration of PoR is informed by the DHRW. The DHRW also drew on a previous RCT evaluation as one of its sources (Anders et al., 2021).

Criteria for selecting a theory to inform teaching

To conclude this article, we suggest criteria that teachers and policymakers might use to select an appropriate theory to inform teaching. A theory should:

- be relevant to the context of the school, its teachers and its pupils

- be a theory of teaching, and not only a theory of learning

- have a robust published evidence base

- have been subject to peer review by researchers

- be tried and tested by sufficient numbers of teachers and judged to be relevant and useful

- result in better outcomes for sufficient numbers of pupils.

While no single model can transform education on its own, the DHRW offers a new, holistic, research-based alternative to more narrow models of literacy. If implemented with sufficient professional development for teachers, we predict that it would result in even better outcomes for children in England and in other countries that have not adopted a balanced approach to the teaching of reading and writing.