LIZ BARRATT, COACHING LEAD, CEFEL, UK; DIRECTOR OF ADULT LEARNING, TRANSFORM TRUST, UK

Context

The current suite of National Professional Qualifications (NPQs) was first delivered in autumn 2021, with an aim of creating a ‘golden thread’ of leadership development, rooted in the best available evidence available throughout a teacher’s career. The Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England contracted nine lead providers to deliver the reformed NPQs in different regions (CFE Research, 2023), including the Church of England Education Office (CEEO) through the Church of England Foundation for Educational Leadership (CEFEL).

Each lead provider designed their own delivery model. CEFEL developed a four-stage model of ‘Activate –Teach – Practice – Apply’, which was described in Impact (Lomax and Watkins, 2023). The deliberate focus on using a coaching mindset and behaviours to support professional learning is one of the four underpinning principles of the CEFEL NPQs and is the focus of the ‘Practice’ stage. This case study explores how we have applied coaching competencies to professional dialogue within a leadership qualification.

What are the coaching competencies?

Many leadership qualifications include facilitator-supported peer dialogue, and our intention was to maximise the impact of this by bringing a coaching mindset and discipline to these discussions. The International Coaching Federation (ICF) adheres to eight core competencies, and we recognised that these would be significant in creating the climate and framework for this dialogue. The eight competencies are:

- demonstrates ethical practice

- embodies a coaching mindset

- establishes and maintains agreements

- cultivates trust and safety

- maintains presence

- listens actively

- evokes awareness

- facilitates client growth (ICF, 2024).

Our aim was to create a shared pause-point for participants to ‘think out-loud together’, while maintaining autonomy over their decision-making (Knight, 2024). This would bridge the gap between engagement with the research and the practical application elements of the NPQ programme. We were keen that participants could explore research, develop their own meaning, consider personal biases and benefit from the reflections of others. We were inspired by the Socrative method, as described by Law and Allen (2008). We recognised the power of questions that encouraged ‘fundamental insight’ by bringing personal knowledge, values and perspectives to the surface through introspection and connection-making.

We were also challenged by Cordingley (2019), who called for professional development that provides ‘an environment in which it is safe to explore evidence about puzzling pupil responses, doubts about understanding or implementation… [T]he focus [has been] on exploring and sharing existing practices rather than incremental development and refinement of new ones.’ (p. 140) We wondered how using coaching discipline in group dialogue could replace the descriptive and repetitive narrative of ‘What happens here/there?’ with a more evaluative lens of ‘What could be?’ and ‘What could we learn from that?’.

It was important to us that we used more experienced leaders to provide disciplined ‘expert input’ as and when it would support understanding. In alignment with the dialogical coaching discipline (Knight, 2024), we differentiated between the advantages of sharing clean perspectives and knowledge, and the risks of providing unsolicited opinion or personal advice. We offered the Chartered College of Teaching’s Certificate in Evidence-Informed Practice (https://chartered.college/certificate) to support coaches in consolidating their understanding of evidence-informed practice and dialogue, complementing this with training that enabled these experts to reflect upon their wider dialogical habits and temptations and practise the competencies described earlier, so that they could be reflexive in their continuing practice.

The CEFEL framework

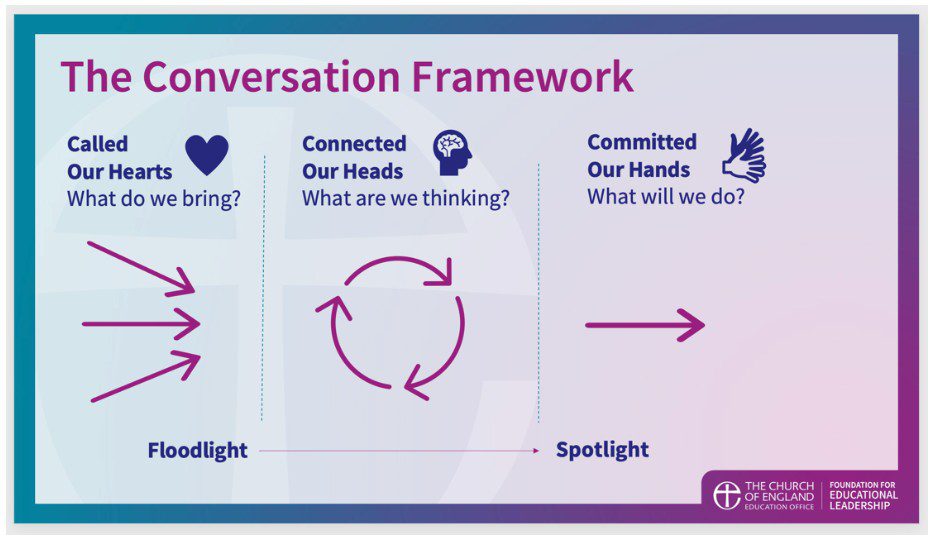

CEFEL leadership thinking is underpinned by 24 called, connected and committed practices (Ford and Wolfe, 2019), and we realised that these three words also reflected three significant elements of coaching behaviour (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The CEFEL conversation framework

Figure 2: A focus on each stage of the framework

The called element focuses on both the cognitive and affective domains to raise awareness of the personal values, perspectives and biases that each person brings to a leadership topic. Connected focuses mainly on our cognitive domain to grapple with how the research relates to our context and how we can expand our thinking and shed light on our developing practice through dialogue with others. Committed focuses on relevant and realistic action and commitment. This stage directs each individual to ask themselves ‘So what? Now what?’ as a result of their reading of the research and their dialogue with peers and the expert coach.

We wanted to floodlight the group’s reading, experiences and perspectives to reveal fundamental insights, before funnelling to spotlight on the areas that could make the greatest difference to each individual’s practice. This head, heart and hands approach, as described in Figure 1, had been informed by the findings of a meta-analysisA quantitative study design used to systematically assess the results of multiple studies in order to draw conclusions about that body of research of coaching research that had unpicked the affective, cognitive and metacognitive benefits of coaching practice (Jones, 2020).

Training for the conversations: Our focus

The ongoing development of our coaches was significant for creating the learning spaces that we imagined. We wanted our coaches to use the framework, while being highly responsive to the needs of each group. We knew that the mindset, behaviours, attitudes and confidence of the coach would be significant ingredients for creating a meaningful learning experience, so how our coaches thought and behaved would be just as important as the framework that they used and the content that they discussed. This was supported implicitly by the competencies.

Our training was carried out both synchronously and asynchronously online, to mirror the majority of our NPQ coaching practice. We delivered sessions that developed understanding of the framework and that explored the core coaching competencies. We created short video conversations to explore ethics and how to face the common challenges experienced in group dialogue. Our community of practice enabled ongoing dialogue and training to build the collective efficacy of the facilitators and coaches.

Our coaches had been carefully chosen for their experience, skills and attributes. They had coached one-to-one or face-to-face, but had less experience of using their coaching competencies in group dialogue and online. Our training therefore concentrated on transferring their skills to this framework and this context. In order to deepen their confidence, we focused on experiential learning, modelled practice and the unpicking of our own beliefs and behaviours.

As facilitators of this training, the coaching leads constantly modelled coaching behaviours and deliberately narrated our processes to help coaches to better understand the competencies that underpinned the framework. Coaches responded well, engaged effectively and modelled peer support and challenge. Over time, coaches have been keen to contribute to the development of the wider community by sharing learning and personal reflections to support the growth of others.

What’s the feedback?

CEFEL collects attitudinal survey data from participants at approximately four points across the completion of their NPQ, rating their experiences from ‘Strongly agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’, with a ‘Neutral’ option (Likert, 1932).

Alongside attitudinal questions, participants are invited to comment qualitatively on their experiences. From all participant surveys (n = 18,911), 92.2 per cent were satisfied that their coaches were knowledgeable and engaging, with just 1.5 per cent dissatisfied and the remainer neutral. Overall, 88.7 per cent of participants felt better equipped to lead others effectively, and just 1.8 per cent did not, although this rises to 93.7 per cent satisfaction when participants are asked at the end of the course.

Participants commented that coaches were ‘very encouraging of me as a fairly inexperienced leader’ and ‘so knowledgeable but also very personable and relatable’. A number of comments noted the pitch of the sessions, which were ‘engaging and challenging (in a good way!)’. Other comments focused on the wellbeing benefits of coaching, and that coaches ‘genuinely care for participant wellbeing and are so generous with their time’. The most common theme was that participants felt that this was a highlight of the course, describing it as ‘the most valuable’ and their ‘favourite’ aspect. This suggests that the significance of coaching competencies 1, 2 and 4 are important to participants.

Analysis of NPQEL coach feedback highlighted the speed at which new groups could build positive learning relationships and engage in meaningful dialogue:

They quickly established a strong sense of trust among themselves, which allowed them to dive into a thorough and frank examination of the intricate problem they had each brought to address during the session.

The group displayed remarkable synergy and cohesion…They rapidly developed a sense of mutual trust, which enabled them to openly and constructively analyse the complex issue they had brought to the table for discussion.

Coaches acknowledged the benefit of a clear and consistent framework and support materials, which enabled the dialogue to be purposeful. The provision was evaluated by OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – a non-ministerial department responsible for inspecting and regulating services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills in June 2024 and was found to be outstanding. There was clear evidence of how the process helped participants to think strategically and make progress from a wide range of starting points. Leaders from participants’ schools were seeing a real difference in strategic decision-making. The process was described as transformative.

A number of key areas of development were identified by participants, with 16 per cent (n = 105) of comments highlighting difficulties around workload and timings of sessions. We know that this is a key issue in the education sector, with teachers and school leaders working substantially longer hours than average (Walker et al., 2019). Moreover, challenges with completing coaching online were noted by a further 11 per cent of qualitative comments (n = 70), with a participant noting, ‘I benefitted more from the face-to-face sessions than the online.’

Overall satisfaction with online technology across the Church of England’s NPQs remains high (at 91 per cent), and a key theme in our evaluation data is the benefits for those from rural areas and with childcare responsibilities. However, it is important for us to review ways in which to improve the online experience, and to benefit from a hybridity of online and in-person experiences to leverage the benefits of each.

In conclusion, we are firm in our ongoing commitment to develop high-quality coaching-informed experiences as part of our NPQ and wider teaching and leadership development provision. We encourage colleagues to further consider how coaching competencies and disciplines might be applied when engaging in professional dialogue and structured conversations.

Thank you to Luke Watkins, Learning Specialist at CEFEL, for data analysis, and to Angie Brown, Coaching Lead at CEFEL.