Note: The author of this article, Lisa Cook, works for Challenging Learning, an organisation offering chargeable support, training and consultancy services to schools on a range of topics including metacognition.

‘The ability to critically analyse how you think’ or ‘thinking about one’s thinking’: these two definitions best capture how I understand metacognition.

Metacognition was a key strand to the development of thinking skills in classrooms, promoted by the Secondary Strategy and groups such as the Northumberland Thinking for Learning Innovation Unit. Of interest to educational researchers for more than 40 years, this remains a hot topic for education, and I am curious as to why it seems to be so elusive in our classrooms.

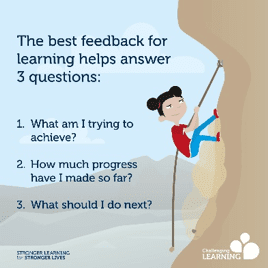

As a secondary history and politics teacher, I valued using thinking tools and encouraged my pupils to see them as transferable, building in metacognition as part of the learning process. I would achieve this by introducing a thinking tool like Edward De Bono’s PMI, where pupils would categorise statements according to their plus points, minus points and interesting points, and illustrating how it could be used effectively to evaluate the impact of an event (like the Rosa Parks and NAACP bus boycott). I modelled my thinking at each stage with reflective questions, enabling pupils to take greater control of their own learning experience. The result of this transferThe processes of applying learning to new situations was deeper learning. Over a period of time, I would use a variety of thinking tools, always being explicit in the metacognition stage. Pupils were then able to choose preferred tools for different tasks, often to make revision a more diverse experience. I often found that a block for successful metacognition was the pupils who ‘just want to get things right and move on’; they were incredibly frustrated by the metacognition process when they first met it, and only when it was embedded into their learning did they begin to see the value. Taking over new classes, I would regularly hear pupils say, ‘This is too hard – can you just tell me?’ Establishing learning routines is key to success, and using strategies such as the three key feedback questions is a powerful and yet effective method to engage pupils in their learning: Where am I going? Where am I now? What are my next steps? (Nottingham and Nottingham, (Nottingham and Nottingham , 2017); see Figure 1).

I worked with groups and individuals to build up the level of challenge, which they were willing to take part in. Pupils who went on to make the greatest progress in my classes were the ones who grasped the significance of this process; this was not ability-linked but, I think, was more to do with their learning outlook.

Many teachers adopt thinking strategies like ‘odd one out’ and ‘mysteries’, as they are fun to do with learners of any age; however, the real impact of these strategies is when the teacher facilitates a deeper thinking about the processes involved with these strategies and encourages pupils to consider how they can be transferred to other subjects. Figure 2 demonstrates thinking through the learning challenge using the ‘Learning Pit’ analogy (Nottingham and Nottingham, 2016).

In schools such as Brechin High School, I and the Challenging Learning team model the learning process to highlight the value and need of metacognition. It gives teachers the experience of going through the ‘Learning Pit’ and having the ‘eureka’ moment of why explicitly teaching metacognition is so valuable. They are far more likely to build in the metacognitive tools if they have experienced the value for themselves. An integral part of the projects is for me to go in for a demonstration day, where I will work with pupils in the classroom to model to staff a key aspect of learning with their pupils. The pre-lesson discussion and follow-up debrief enable me to coach the group of staff to develop their understanding.

We invest time into learning about and encouraging others to build metacognition into the learning process because we have research to show that this strategy increases academic achievement (Biggs, 1988). More recent studies, such as research by the Sutton Trust-Education Endowment Foundation (Education Endowment Foundation , 2018) for their Teaching and Learning Toolkit, rates developing metacognitive skills as one of the cheapest interventions that schools can do. The evidence is clear and consistent: teaching pupils specific metacognition strategies will enable faster progress in learning, so is worth the investment of time.