Title:

Using authentic picture books and illustrated books to improve L2 writing among 11-year-olds

Published in:

The Language Learning Journal, 45:1, 100-116, 2018.

Authors:

Anna Birketveit

Hege Emma Rimmereide

Both from Bergen University College, Norway.

What did the research explore?

The research explored how pupils’ writing skills were affected by reading picture and illustrated books, when they were given the freedom to choose what to read. The research attempted to answer two questions:

- What impact did extensive reading of picture books/illustrated books have on learners’ writing skills in English?

- How important were the pictures/illustrations for the learners and what type of picture-text interaction did they favour?

How did they conduct the research?

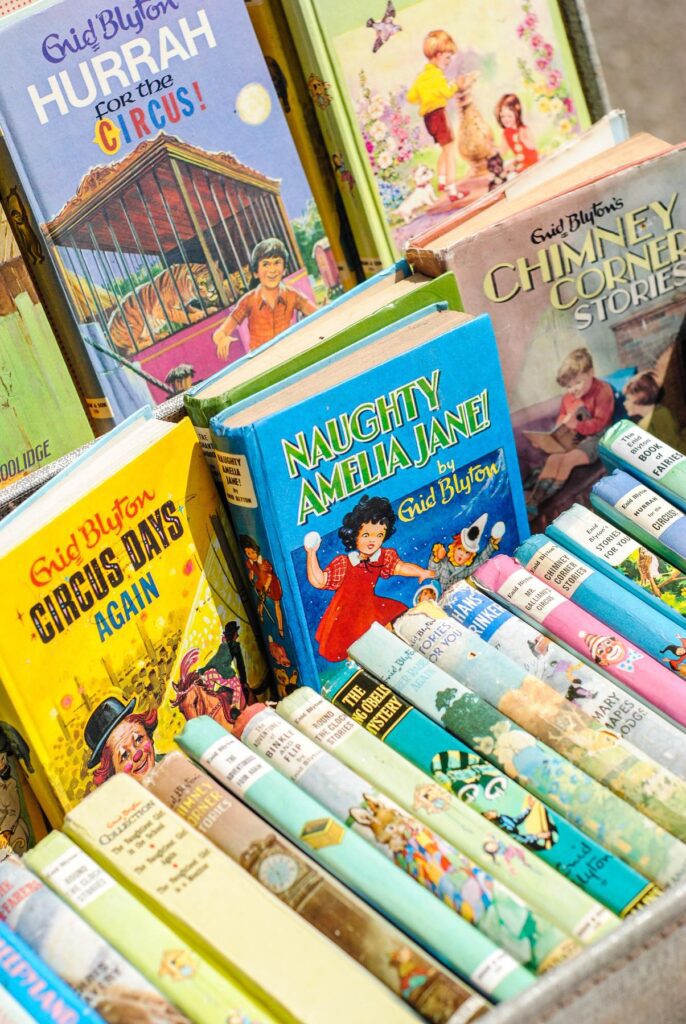

The research was conducted through a five-week reading project with an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) class in Norway. There were 21 students in the study, all aged 11 (6th grade in the Norwegian system). Researchers chose 70 books for the project – there were 32 picture books proper, and 38 richly illustrated books. The books were chosen from a range of genres, including fiction and non-fiction. As part of the project the students had to read as many books as possible, but at least three. The research was focused on how the children used the books as part of independent learning, rather than teaching – after an introductory lesson, the children used the books independently.

Researchers collected qualitative and quantitative data. They looked at: student logbooks, in which pupils were asked to write and draw; a closed, student questionnaire; semi-structured interviews with 20 students; and two pieces of written work – one completed by students before the project, and one after.

The researchers visited the class at the midway point of the project and on the last day when students were interviewed about their questionnaire. The researchers said the ‘aim was to find out more than the questionnaire revealed concerning learners’ enjoyment of the project, learners’ perceptions of their own progress and learners’ perceptions of picture-text interaction’ (Birketveit and Rimmereide, 2018, p. 106).

…pupils’ perceived progress was modest compared with their actual writing results…

What were the key findings?

Enjoyment

The questionnaire responses and interviews confirmed that the majority of students responded positively to the project – 12 of the 20 students interviewed described it as ‘fun’. The authors said that ‘by allowing the pupils to select books themselves from a list provided, it is likely that there was a closer match between their competence and language skills’ (Birketveit and Rimmereide, 2018, p. 108). This resulted in an appropriate level of challenge and increased enjoyment.

Progress

Eighteen of the students interviewed believed that their English had improved as a result of the project. The authors, however, maintain that pupils’ perceived progress was modest compared with their actual writing results. The before-and-after writing test examples showed that ‘learners’ writing had improved significantly concerning their use of adverbials and story-building skills’ (Birketveit and Rimmereide, 2018, p. 108).

The students were asked to write two texts, one at the start and one at the end of the project. The passages were based on two illustrations (one for each writing test) showing somebody in a scary situation. According to the authors, most students wrote a longer second text (average 86 words in total) compared with the first (average 62 words in total), as well as showing improved story-building skills.

The difference in the number of adjectives and adverbials pupils used in the before-and-after writing tests was analysed using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, which researchers use to compare two related samples (in this case the number of adjectives and adverbials used). The results showed that the number of adverbials used had increased significantly after the project, but there was no notable change in the number of adjectives.

Perception of picture-text interaction

Results for this were mixed. Of the 20 students who took the questionnaire, 13 claimed the pictures were important when reading a story, while just seven pupils did not think they were. Also, ‘they seemed largely conventional in their preference for pictures and text to say the same, but also seemed aware of the thrill of pictures enhancing the story’ (Birketveit and Rimmereide, 2018, p. 109).

What are the limitations?

- One of the limitations is the small sample size of the study, which limits how generalisable the results are

- The authors also recognise that, as there was no control group, improvements in the students’ texts might have occurred without the intervention

- Another possible limitation was ‘the presence of the researchers in the classroom at the beginning and end of the project when the texts were written, which may have influenced the learners’ motivation and performance.’ (Birketveit and Rimmereide, 2018, p. 114)

- Although the researchers asked the students to keep log books, these are not used at all in the data analysis process. This doesn’t necessarily undermine the results, but it is a layer of insight that has not been used.

What ideas might you adopt for your own classroom from the research?

- Try to increase the amount of freedom students have in choosing the books they read

- Aim to expand the use of picture/ illustration books to support learning across subjects, but especially in teaching Modern Foreign Languages (MFL)

- Look for ways to use picture/ illustration books to help support EAL students.

What questions does the research raise for teachers?

- Does providing students with greater autonomy over the texts they choose increase their motivation to read?

- Does allowing students to select their own texts lead to an increase in engagement and enjoyment of reading?

- How can picture/ illustration books be used to support EAL students in developing their written English?

- Could a similar approach be adopted for teaching MFL subjects?