How can issues of validity and reliability be addressed to strengthen internal school assessment?

A case study of how teachers can improve the validity and reliability of assessment

Tom Johns, Associate Assistant Headteacher – Assessment and Reporting, Kingsmead School, Somerset, UK

After completing the ‘Assessment Essentials’ course from Evidence Based Education as part of my role, which leads on assessment and reporting, I wanted to deliver inset on making our school’s summative assessments stronger. The objective was to build capacity within staff to change their attitudes towards their approach to assessment and to make sure that all assessment had a purpose (what inferences do you want to make?) and that all staff were aware of how to improve the reliabilityIn assessment, the degree to which the outcome of a particular assessment would be consistent – for example, if it were marked by a different marker or taken again (if students did the paper again, would the outcomes be the same?) and validityIn assessment, the degree to which a particular assessment measures what it is intended to measure, and the extent to which proposed interpretations and uses are justified of assessment (how and when was the paper constructed? How is it marked?). This case study will look at how this was approached, what lessons have been learnt and how they could be embedded in other schools.

Since Black and Wiliam (1998a) published their groundbreaking research on raising standards through classroom assessment, there has been a greater focus during teacher training on formative assessment. Black and Wiliam (1998b) define formative assessment or ‘AFL’ (assessment for learningKnown as AfL for short, and also known as formative assessment, this is the process of gathering evidence through assessment to inform and support next steps for a students’ teaching and learning) as assessment that happens inside the classroom. Hargreaves (2007) adds to this by saying that it enhances students’ learning compared to summative assessment, which simply measures learning. For learning to be effective, there needs to be a blend of both types of assessment rooted in schemes of work, with a clear understanding of when and why the assessment strategy should be used. Dixson and Worrell (2016) make the distinction clear when they say that the difference is related to how the results are used. Over the past 10 years, the AFLAssessment for Learning (also known as formative assessment) - the process of gathering evidence through assessment to inform and support next steps for a students’ teaching and learning ideas that have found their way into the classroom have been criticised and later developed to improve their effectiveness; however, arguments still continue between practitioners over what formative assessment is (Dolin et al., 2018). The questions that we should be asking are whether these ideas are reliable and whether they are valid.

Many AFL ideas are now embedded in teacher toolkits up and down the country, many of which are now second nature to many practitioners. However, there is often great attention given to summative assessment, as it is far more tangible than formative assessment. In the current climate of data collection and targets, summative assessment data often provides some kind of evidence that students are making progress and are on track to achieving their target grades – or not. Quite often, these summative assessment tests have been in department bases for many years and reused time and time again. More often than not, they are not reliable or valid and so are not fit for purpose.

Validity

Crooks et al. (1996) argue that validity is the most important part of any assessment and they offer up a chain of assessment. Each link in the chain needs to be considered in detail to ensure that the assessment is valid, and if one link is often weaker than the others, this limits the validity of the assessment, even if another link is very thought-through. The chain starts with the administration of the assessment, followed by how it is scored, the diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences of the added constructs, the reliability of the assessment, what interpretations are made from the constructs, and bias and judgemental marking decisions, as well as the impact on students. We may often think of validity in terms of fairness (Sambell et al., 1997), so maybe it is time to reflect on when we have dismissed students’ moans of ‘It’s not fair’ and to focus on what link of the chain of validity was broken.

During the inset, it is fair to suggest that several colleagues struggled to grasp the idea of validity and how it was linked to purpose. For an assessment to begin to be considered valid, it must be free of bias, particularly confirmation bias, and have a purpose in mind with appropriate constructs, in order to make suitable inferences based on the results of the assessment. I allowed colleagues to reflect on recent assessments and the constructs that were tested to discuss whether the assessment actually measured what it was supposed to measure. If you have a test on cells and you award students a grade (possibly dangerous ground), would you be confident that all areas of learning (constructs and skills) were covered? Was there any construct under representation (are some areas of the learning harder to assess than others)? And what about construct irrelevance variance (are there questions that require high skills of literacy that students cannot access to get the answer, such as wordy maths questions)? Above all, does the assessment contain questions that are not relevant to the topic that you are testing? Thinking about all of these points, are your assessments valid?

Reliability

Reliability is often used interchangeably with validity. It is important to separate them, however, as you are able to have a reliable assessment that is not valid. However, for an assessment to be valid, it must be reliable. Reliability is an easier concept to understand if we think of it as a student getting the same score on an assessment if they sat it at 9.00 am on a Monday morning as they would if they did the same assessment at 3.00 pm on a Friday afternoon. How often have you planned to do a test at a certain time of day because it is easier for you? I know I have, but now, on reflection, can you be certain of the inferences made from it? Where did students sit for it? Were they hungry? Was it after PE? Before PE? Who marked it? Would a colleague give the same score if they marked it?

It is important for teachers to get the balance right between reliability and validity. If you have more of one without the other, your inferences will be limited and the task may become unmanageable. Using multiple-choice testing is very reliable but, due to the nature of the questions, is less valid compared to longer-answer questions, which are more valid but less reliable. No matter how hard you try, you will not reach a point where an assessment is both valid and reliable, but it is important to get the balance right between the two. This can only be done if the person giving the test knows its purpose and what inferences they want to make.

The changing face of assessment in 2021

With centre- and teacher-assessed grades being issued by schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Ofqual, 2021), it is an ideal time for there to be a paradigm shift when considering the impact and effectiveness of the assessments completed in schools. Every teacher wants their students to perform well and succeed, and having quality valid and reliable assessments will allow them to put their best foot forward.

Rethinking professional learning – beyond assessment ‘literacy’

Simon Child and Sally Brown, Cambridge Assessment Network, Cambridge Assessment, UK

The COVID-19 pandemic has reopened the debate about the future role of teacher assessment, both in high-stakes testing and when ensuring good learning outcomes. Teachers have a unique perspective on the merits of proposed changes in assessment in relation to validity, reliability, fairness and accessibility. Assessment is only valid for teachers when it measures what it intends to measure and when it is able to provide information that is useful for a defined purpose. Purposes for assessment can range between informing teachers’ instructional decisions and determining broader grading judgements. The challenges to teaching, learning and assessment presented by the pandemic mean that teachers must innovate when collecting and interpreting information about student knowledge and understanding. For example, the pandemic has meant that for general qualifications, teachers are now responsible for judging assessment evidence in the context of high-stakes qualifications.

With the emerging imperative for innovation in classroom assessment for either learning or summative judgement purposes, it is important to consider the mechanisms that facilitate the development of empowered and confident assessment teacher-practitioners. The aim of this article is to offer a new research-led framework for conceptualising professional development to strengthen internal school assessment.

Supporting valid innovations in school-based assessment

Innovations in assessment are driven by the intention to improve pedagogy or to encourage independent student learning. In many cases, however, teachers are innovating to respond to perceived ‘pain points’ such as unmanageable workload (Centre for Education and Youth and Pearson, 2020). This reflects an inconvenient truth that there is often little time available for teachers to step back and reflect on their own assessment practice or that of their department, school or trust.

The importance of embedding assessment professional development into day-to-day teacher practice is reflected in recent standards-based professional frameworks. The ‘Early Career Framework’ (Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2019) and the ‘Professional standards for teaching and leadership’ (Welsh Government, 2017) align with ideas of assessment ‘literacy’, which, broadly defined, relates to the ability of teachers to interrogate and use assessment appropriately (Stiggins, 1991). By ‘appropriately’, Stiggins refers to an understanding of how different purposes for assessment connect to design decisions and how assessment outcomes feed back into teaching.

Whilst building expertise, confidence and agency in assessment is identified as essential for effective teaching, it has been argued that conceptualisations of teacher assessment expertise are rather static and limited (DeLuca et al., 2019). A predominant focus on developing assessment literacy underplays the intimate connection between the attitudes and beliefs that teachers hold about assessment and their classroom activity (Brown et al., 2019).

Alternative conceptualisations of teachers as assessors have focused not just on their technical knowledge but also on the socio-cultural context and policy frameworks within which teachers work (Adie, 2013; Looney et al., 2018; Xu and Brown, 2016). Going beyond ‘literacy’, this situated view of professional learning in assessment encompasses reflective components that prompt teachers to re-examine their values, conceptions and beliefs about the role of assessment in times of change. This approach is sensitive to teachers’ confidence and the self-efficacy that underpins their assessment practice.

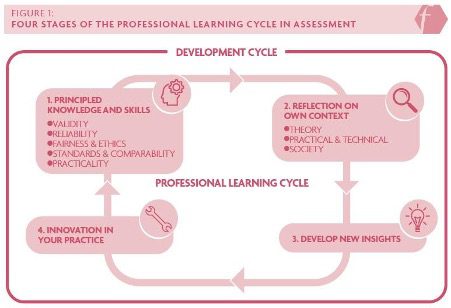

How can this view of teachers as assessors inform professional development? We suggest that impactful professional learning in assessment is underpinned by four interrelated stages that form a development cycle. This cycle is illustrated in Figure 1, and draws upon professional learning models (e.g. Kolb, 1984) that regard innovations as emerging from a synthesis of lived experiences with active opportunities for reflection and experimentation. We outline each stage below.

Figure 1: Four stages of the professional learning cycle in assessment

- Principled knowledge and skills

Principled knowledge and skills in assessment relate to the key concepts and understanding required for teachers to engage with the issues and debates that they will encounter in their day-to-day practice. Teachers can engage with assessment principles including validity, reliability, fairness and ethics, standards and comparability, and practicality within three broad themes: theory; practical and technical; and societal. Principled knowledge and skills represent a common entry point for professional learning in assessment. Professional learning activities that develop knowledge and understanding of assessment principles act as an external source of information or a stimulus (Boylan et al., 2018). The active learning processes that accompany the learning of principled knowledge and skills represent an important mechanism to enable reflection to take place.

- Reflection on own context

Assessment practice is implemented in subject-specific and context-dependent circumstances, and so learning in assessment is most optimal when teachers are able to situate assessment knowledge and understanding within their working practice – what Weston and Clay (2018) refer to as ‘direct impact’. Situating reflective practice in assessment within the context of subject disciplines, curriculum outcomes or student age (amongst many other things) acknowledges the important role that teachers play in using their pedagogical content knowledge to inform valid assessment design and use. The main reason for the status of reflective practice is that it serves a dual role of enabling a sense of agency in teachers, in addition to allowing them to orient themselves to the key challenges that their learning has uncovered (Boylan et al., 2018).

- Develop new insights

Teachers’ conceptions of teaching, learning and curricula strongly influence how they teach and what students learn or achieve (Levy-Vered and Alhija, 2018). Xu and Brown (2016) argue that teachers hold and maintain beliefs about assessment, which act as a prism for how they reflect on new knowledge. Teacher identities are framed and reframed over the course of a career and are rooted in systemic and social factors (Looney et al., 2018). These change as a result of completing professional learning that reveals and challenges previously held conceptions and leads to new conceptual insights. This is an important prerequisite for encouraging innovations in practice.

- Innovations in practice

Effective professional learning encourages teachers to adapt their practice in informed ways. Once potential improvements to assessment practice have been hypothesised, teachers need the opportunity to plan, enact and evaluate the changes that they have made. This process is again reflective, as teachers evaluate the effectiveness of their interventions or changes to their practice. The teachers become a source of principled knowledge about assessment, thus completing the professional learning cycle.

The changing culture of assessment

We argue that the development cycle outlined above is a useful framework to support teachers’ understanding of how curriculum decisions, pedagogy, accountability arrangements and institutional structures influence assessment practice in the classroom – what has been termed the ‘assessment culture’ (Xu and Brown, 2016). In the United Kingdom, the pandemic has forced a step-change in the relationship between teachers and national assessment policy that will have lasting implications for trust in assessment and for broader education. Empowering teachers to examine and potentially challenge the assessment cultures that they inhabit can help to build confidence, aid the development of shared beliefs about the role of internal assessment and inform the implementation of valid assessment innovations in times of systemic change.

References

Adie L (2013) The development of teacher assessment identity through participation in online moderation. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 20(1): 91–106.

Black P and Wiliam D (1998a) Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. London: Granada Learning.

Black P and Wiliam D (1998b) Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education 5(1): 7–74.

Boylan M, Coldwell M, Maxwell B et al. (2018) Rethinking models of professional learning as tools: A conceptual analysis to inform research and practice. Professional Development in Education 44(1): 120–139.

Brown GTL, Gebril A and Michaelidis MP (2019) Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: A global phenomenon or a global localism. Frontiers in Education: Assessment, Testing & Applied Measurement 4: Article 16. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00016.

Centre for Education and Youth and Pearson (2020) Making waves: A better future for assessment. Available at: https://cfey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/40110-UK-Making-Waves-research-report-Final-SMALL-WEB-VERSION-1.pdf (accessed 25 March 2021).

Crooks TJ, Kane MT and Cohen AS (1996) Threats to the valid use of assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 3(3): 265–286.

DeLuca C, Coombs A, MacGregor S et al. (2019) Towards a differential and situated view of assessment literacy: Studying teachers’ responses to classroom assessment scenarios. Frontiers in Education 4: Article 94. DOI: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00094.

Department for Education (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England) (2019) Early Career Framework. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/913646/Early-Career_Framework.pdf (accessed 25 March 2021).

Dixson DD and Worrell FC (2016) Formative and summative assessment in the classroom. Theory Into Practice 55(2): 153–159.

Dolin J, Black P, Harlen W et al. (2018) Exploring relations between formative and summative assessment. In: Dolin J and Evans R (eds) Transforming Assessment. Switzerland: Springer, pp. 53–80.

Hargreaves E (2007) The validity of collaborative assessment for learning. Assessment in Education 14(2): 185–199.

Kolb DA (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Levy-Vered A and Alhija FN-A (2018) The power of a basic assessment course in changing pre-service teachers’ conceptions of assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation 59: 84–93.

Looney A, Cumming J, van Der Kleij F et al. (2018) Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: Teacher assessment identity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 25(5): 442–467.

Ofqual (2021) Consultation decisions: Decisions on how GCSE, AS and A level grades will be determined in summer 2021. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/965005/6747-1_decisions_-_GQ_consultation_on_awarding_grades_in_2021.pdf (accessed 19 March 2021).

Sambell K, Brown S and McDowell L (1997) ‘But is it fair?’: An exploratory study of student perceptions of the consequential validity of assessment. Studies in Educational Evaluation 23(4): 349–371.

Stiggins R (1991) Assessment literacy. Phi Delta Kappan 72: 534–539.

Welsh Government (2017) Professional standards for teaching and leadership. Available at: https://hwb.gov.wales/api/storage/19bc948b-8a3f-41e0-944a-7bf2cadf7d18/professional-standards-for-teaching-and-leadership-interactive-pdf-for-pc.pdf (accessed 25 March 2021).

Weston D and Clay B (2018) Unleashing Great Teaching: The Secrets to the Most Effective Teacher Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

Xu Y and Brown G (2016) Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education 58: 149–162.