Applying Rosenshine to Religious Education

In 2012, Barack Rosenshine published the Principles of Instruction: a set of 10 research-based principles of instruction, along with suggestions for classroom practice. The principles come from three sources: (a) research in cognitive scienceThe study of the human mind, such as the processes of though, (b) research on master teachers, and (c) research on cognitive supports.

The 10 Principles of Instruction are as follows:

- Principle 1: Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning: Daily review can strengthen previous learning and can lead to fluent recall.

- Principle 2. Present new material in small steps with student practice after each step. Only present small amounts of new material at any time, and then assist students as they practice this material.

- Principle 3. Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students: Questions help students practice new information and connect new material to their prior learning.

- Principle 4. Provide models: Providing students with models and worked examples can help them learn to solve problems faster.

- Principle 5. Guide student practice: Successful teachers spend more time guiding students’ practice of new material.

- Principle 6. Check for student understanding: Checking for student understanding at each point can help students learn the material with fewer errors.

- Principle 7. Obtain a high success rate: It is important for students to achieve a high success rate during classroom instruction.

- Principle 8. Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks: The teacher provides students with

temporary supports and scaffolds to assist them when they learn difficult tasks. - Principle 9. Require and monitor independent practice: Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic.

- Principle 10. Engage students in weekly and monthly review: Students need to be involved in extensive practice in order to develop well-connected and automatic knowledge.

In this post, Dawn Cox, explores their application in religious education.

This content was originally produced as part of the Accelerate programme, a Department for Education-funded early career teacher programme designed and delivered by Education Development Trust with the Chartered College of Teaching. It is used here with kind permission of Education Development Trust.

Principle 2: Present new information in small steps and have children practice after each step is introduced

It’s highly likely that daily review will not be possible as for many pupils, RE happens only once a week or even once a fortnight. However, you can still apply the detail of this principle and begin each lesson with a short review of previous learning.

A quiz at the start of the lesson can be a great way to do this. In my lessons, students are given a piece of scrap paper and depending on how much time is available, I ask them to write the numbers 1-10 and pose a series of questions based on content from previous lessons: this tends to be composed of a few questions from a long time ago; from a few weeks ago; and from last lesson. The review usually starts with some easier questions to develop their confidence, which means they should at least know the answer to question number 1!

Due to teaching so many classes, it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish exactly what has been taught to each group so I usually use one of the pupils’ books to help me; typically a student that writes a good amount of independent notes which I then use as a basis to ask the questions. I don’t spend time preparing these questions, but you could easily do this and type them onto a powerpoint slide if it helps you in your lesson preparation.

I allow pupils to self-mark these quizzes, asking specific students for the answers which means I can target individuals as needed. This purpose of this quiz is not about getting a high score but rather the exposure to previously studied content; it’s a review activity rather than an assessment activity. At the end of the review I encourage pupils to put their hand up to signal the score they got – again, this is almost irrelevant as I don’t record their scores, but it does give me a helpful overview.

Even if your quiz is just a few questions, it’s an easy way to recap previous learning. Don’t worry about it taking up lesson time; this type of retrieval helps with long term memory recall so is worth the time spent (Roediger & Karpicke 2006).

Principle 4: Provide models

One way that I provide models for students is through an activity that I call ‘Be the teacher’. This applies to written work where students will need to include specific elements in their writing.

It is important that the students know what they are looking for in a model answer (- see Sadler 2002 for an example).

For example, I might be looking for ‘use of a quotation from a source of wisdom and authority’. I present this in two different ways:

- In Key Stage 3 I show short prepared answers on the screen for them all to see. The first example is ‘perfect’ and has all the required elements. Then each subsequent answer has a key feature omitted or misused. Students then have to identify what the prepared answer is lacking. It’s almost like a ‘spot the difference’. If they can explain what the answer is missing it should help them to understand what they need to include in their own answer. They then write their own answer trying to include the elements required. Whilst they are writing, I then ask them to evaluate their own work in the same way:. I put the ‘perfect’ example back on the board and as pupils to check to see if they’ve included the elements in their own answer. They could also complete this activity with a peer if you preferred (see Ormsond et al 2002).

- At GCSE I give them a sheet with ‘student answers’ to an exam question on it. I have written these student answers specifically to include or omit important aspects of what the answer needs. Some are obvious errors or omissions and others are more subtle. They can then use highlighters to highlight the elements needed in the answers and complete a ‘what the student has done well’ and ‘what the student needs to do to improve their answer’ chart. Again, this enables pupils to practice identifying the key elements of a specific type of question so that when they come to write their own answer, they can transferThe processes of applying learning to new situations these important aspects in to their own work.

In our department we think that modelling answers to students is so important that we have developed a scheme across the GCSE that specifically includes planned modelling to ensure that all classes experience as many modelled answers as possible, hopefully without too much overload. Once you’ve made your models, you can re-use them with all your classes in that year group which should help with workload.

Principle 3: Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students

RE is about asking lots of questions about religions, beliefs and views. Asking questions and discussion is a huge part of my lessons, and may take the following forms:

Re-cap questions: After the review quiz I start the next phase of my lesson with a specific type of questioning. Students are asked to open their books/folders on the notes from the last lesson. I then directly ask specific students questions based on that lesson. I allow the students to read their notes for the answers if they need to. This teaches them that their notes have some use! No student can say ‘I don’t know’ because the answer is in front of them. I give them time to find the answer if needed. This is a low-threat type of questioning as they all have the answers. I deliberately ask questions that I know will link to the current lesson. I don’t usually plan these in advance, but you could easily do this as part of your planning if you want to be sure which questions you want to ask and if appropriate, decide who you are going to ask. For example, I might ask a specific question to a student that I know had a misconception last time or who answered something incorrectly.

Asking questions to generate discussion: Rosenshine gives a set of question stems that teachers can draw upon to ask useful questions and we can potentially encourage students to use these sentence stems too. Asking questions that open up discussion in RE is a skill that can be developed by thinking about what the key issues are that you want the students to discuss. When discussing moral issues, asking students if they ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ is one way to get students to engage, although this needs to be done with care. I only ever allow students to offer an opinion on these in class if they want to. Allowing them to discuss in a pair or as a ‘table’ might be more appropriate and research on this dialogic method of teaching has shown positive effects (Luby 2018).

Principle 9: Require and monitor independent practice

One way in which my department encourages students to practice and become fluent in their knowledge of key ideas at GCSE is through our quizzing homework. We have designed and created quizzes for all the topics taught at GCSE. These have been made as a multiple choice quiz using Google Forms. Typically we try to limit each quiz to about 10 questions that each have 4 possible answers.

Using these quizzes has a two-fold benefit. Firstly, it means that pupils are being exposed to previously-learnt material (this may be from a recent topic and/or a topic studied a while ago). Secondly, this quizzing requires pupils to retrieve the answers from their long-term memory so is therefore a form of spaced retrieval. Together, these support pupils in developing fluency.

Students must retake the quiz until they get full marks. This prevents them from just selecting an answer at random in order to get their homework done and also means that they must engage with the correct answer/s. This homework is great for those of us that have many classes in RE as it doesn’t require any marking yet is an effective use of pupils’ homework time. As teachers all we need to do is to check that all students have completed the quiz and achieved full marks as required.

In our RE schemes of work we have also identified which particular exam questions students will complete and when they will complete them as part of their independent practice. This is particularly helpful if you work in a department with many colleagues and/or non-specialists as it means everyone is aware of what is required and when. These exam-preparation questions come in various

forms, for example once a week pupils have a keyword/quotation test. These are low-stakes but we expect everyone to do their best and improve where possible.

Pupils then have practice exam questions throughout each half term, ranging from the short recall type questions to the more lengthy exam questions. By planning these in advance every student in each year group has the same, planned, experience of independent practice, regardless of their class or teacher. A shared plan ensures all staff remember to complete the questions with their class and allows us to discuss how students got on within our department meetings. We don’t give students any marks or grades on these: the purpose is for the experience of practice and to support pupils in improving their answers.

Finally, students also have to complete yearly ‘exams’ that will pull together all the different topics and skills that they have studied so far on the course. This is good practice in terms of how they use their time and for coping with multiple exam questions. For me, the more independent practice that students have in the ‘low stakes’ means that when it comes to perceived ‘high stakes’ situations, pupils will be able to cope better as they will have developed greater confidence and will be less anxious (See Effortful Educator blog for useful summary of research).

Principle 2: Present new material in small steps

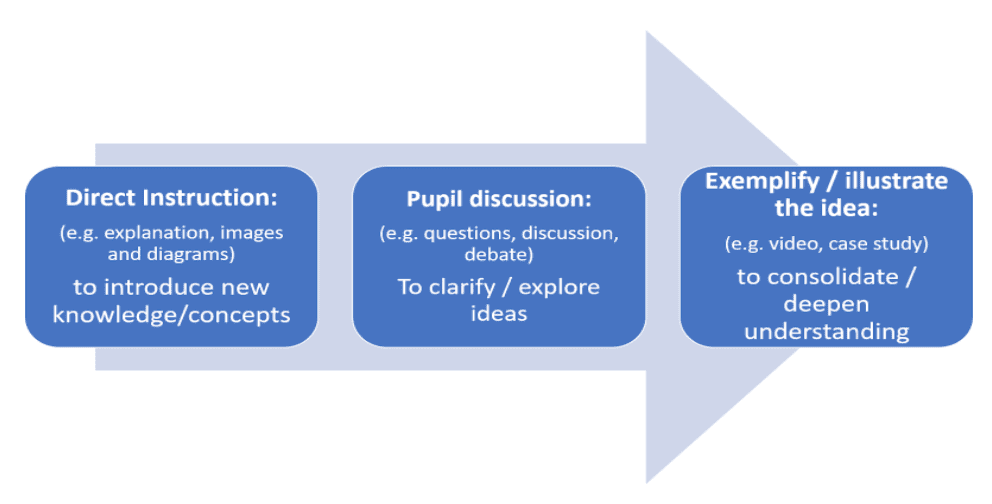

When teaching something new to students, I use several different resources to introduce them to this knowledge. Most of the time I present the initial information by ‘direct instruction’; that is, through explicit teaching and demonstration which tends to be a mixture of me talking, using the whiteboard for keywords and simple images / diagrams, and (where needed) simple PowerPoint slides with subject-specific images, for example a relevant map.

I use high-level subject vocabulary whenever I can and will use etymology to help explain the background to the words, that can enhance their understanding of the keyword.

For example, the term ‘incarnation’ comes from the Latin ‘carn’ meaning flesh, so Jesus was God ‘into flesh’. Using such vocabulary also tends to create a high level of challenge which students seem to enjoy.

I try to link any new information with something they already know to help students make connections between key concepts. This helps to store the new information into their memory. Whilst I insist on silence whilst I am explaining (and encourage note-taking), students can ask questions. It’s these questions that may help develop their understanding or remind me to add extra detail to my exposition. In my experience students can ask quite thoughtful and relevant questions which often help to unpack any misconceptions or misunderstandings. This class discussion adds to them remembering the new information as they are processing their own thoughts on it and applying the information into new contexts. Where appropriate this might include a simple debate with students presenting varying views on the content which may either counter or add to another student’s comment.

I next try to illustrate or exemplify this new content, usually with a video clip and/or a case study. In RE it can be difficult to expose students to the wide range of beliefs, teachings and practices that we study within the classroom, and a well-chosen clip can help them to develop their understanding. I will choose a clip that repeats some of the key information that I have taught, and maybe extend the ideas in some way. This will be the students’ second exposure to the content. When I show video clips, I always ask students the same questions once it has finished; ‘What comments or questions do you about the clip?’. This allows me to again address any misconceptions or to consolidate and further develop their understanding.

The diagram below summarises these three phases of presenting new material:

This process means that they hear the content from:

- me;

- each other; and

- another source.

Overall, this triple exposure, along with the strategies referred to in the four principles outlined above (such as quizzing at the start of the next lesson) seems to help pupils remember, recall and understand the ideas more effectively.

References

Luby A (2018) Dialogic RE: Oracy for the 21st century In IMPACT Journal, Chartered College of Teaching (accessed 16 December 2020)

Orsmond P, Merry S and Reiling K (2002) The use of exemplars and formative feedback when using student derived marking criteria in peer and self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 27(4). 309-323.

Roediger HL and Karpicke JD (2006) Test-enhanced learning taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science. 17: 249-255.

Sadler DR (2002) ‘Ah!…So that’s “quality’. In: Schwartz P and Webb G. eds. Assessment: Case Studies, Experience and Practice from Higher Education. London: Kogan Page. pp. 130-135.

The Effortful Educator (2019) Retrieval Practices’ Impact on Test Anxiety and Stress in The Effortful Educator -Applying Cognitive Psychology to the Classroom. Available at: https://bit.ly/31Zmdn0 (Accessed 16 December 2020)

View the Principles of Instruction research paper

Return to the Principles of Instruction collection

Extremely relevant and useful examples of how to include Rosenshine’s principles in the RE classroom. Thank you!

A very helpful article. I liked how the low stakes quizzing progresses to planned short and long exam questions thereby reducing anxiety and stress. Thank you.