JULIET KOTONYA AND KATHERINE ASTON, NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH, UK

Introduction

England’s pupil population is becoming increasingly ethnically diverse, yet the ethnic make-up of the teaching workforce remains unrepresentative (Demie and Huat See, 2022). This shows up in schools as disparities in who enters teaching, who remains and who progresses into leadership. Representation of teachers from minority ethnic backgrounds shows the sharpest drop in teacher training and early career stages, and this is compounded throughout a teaching career, so is most pronounced among senior leaders and headteachers (Worth et al., 2022). For schools, this imbalance is more than a demographic concern; it goes to the heart of fairness, inclusionAn approach where a school aims to ensure that all children are educated together, with support for those who require it to access the full curriculum and contribute to and participate in all aspects of school life and educational integrity.

To investigate how and why these disparities persist, the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), funded by Mission 44, explored ethnic disparities across three key career points: entry into postgraduate initial teacher trainingAbbreviated to ITT, the period of academic study and time in school leading to Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) (ITTInitial teacher training - the period of academic study and time in school leading to Qualified Teacher Status (QTS)), retention in state-funded schools and progression to leadership (Kotonya et al., 2025).

Using large-scale datasets from the Department for Education’s ITT Apply platform and the Working Lives of Teachers and Leaders (WLTL) survey (Adams et al., 2023), we undertook Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition analysis to explore the factors that may help to explain the ethnic disparities in ITT rejection rates, intention to apply for promotion and intention to leave the state-funded sector. We also undertook focus groups with ITT providers and school leaders to understand their experience of ethnic disparities and approaches to addressing them.

This work builds on the NFER’s 2024 evidence review of ethnic diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences in the teaching workforce (Sharp and Aston, 2024), which examined the wider body of research on representation, progression and lived experience. While the review synthesised existing findings, this study clarifies the nature and extent of the barriers faced by ethnic minority teachers and ITT candidates, and the approaches that schools and ITT providers are using to address them. The study contributes to a growing body of evidence highlighting that workforce diversity does not occur by chance; it must be cultivated through inclusive systems and sustained support. The two reports together offer a fuller picture of both the scale of the challenge and the practical levers for change.

We will use the UK government’s preferred style for writing about ethnicity. This is because it is aligned with the categories that were used to collect the data that we have used in our analysis and is underpinned by user research and testing. Our research compares five major ethnic groups, as used in the census for England and Wales: Asian, Black, Mixed, White and Other ethnic groups.

1. Entry into initial teacher training (ITT)

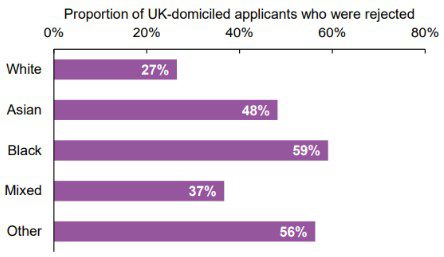

The research revealed that UK-domiciled applicants from Asian, Black, Mixed and Other ethnic groups are significantly more likely to be rejected from postgraduate ITT courses than their White counterparts (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proportion of UK-domiciled applicants rejected from postgraduate ITT courses by ethnicity (Kotonya et al., 2025, p. 25)

Decomposition analysis shows that this disparity persists even after accounting for factors like age, region and socio-economic status. Our analysis suggests that if UK-domiciled applicants from all ethnic backgrounds were the same age, had similar socio-economic backgrounds and applied to the same providers, there would still be a gap in rejection rates between applicants from White and Asian ethnic backgrounds of 14 percentage points. Similarly, the gap would be 18, six and 18 percentage points for applicants from Black, Mixed and Other ethnic groups, respectively. If these gaps were closed, this would represent around 1,400 to 1,700 additional trainees per year.

The persistence of ethnic disparities that are not explained by the characteristics of the applicant that we can observe in the available data suggests that discrimination by ethnic background is likely to play a role, although we cannot definitively rule out other factors (such as differences in qualification levels or work experience). In focus group discussions, ITT provider staff pointed to concerns about potential bias in selection procedures, including culturally biased interpretations of English language skills and professionalism, alongside limited tailored support for diverse applicants and a lack of representation among ITT staff. Providers were developing equity-focused recruitment strategies, such as transparent processes and proactive outreach to underrepresented groupsThe diversity of research participants should reflect the educational community for whose benefit the research is taking place. When this is not the case, some groups are underrepresented.

2. Retention in the state-funded sector

Disparities do not end at entry to the teaching profession. For example, teachers from a Black ethnic background are more likely to consider leaving state-sector teaching than their White counterparts (33 per cent, compared with 28 per cent). Our analysis showed that this reflects differences in lived experience of teaching. Teachers from a Black ethnic background were more likely to report experiences of bullying, not feeling valued by their school and that a lack of support from superiors was an important reason for considering leaving, compared with teachers from a White ethnic background. These findings align with other recent research into staff wellbeing and racialised workplace stressors (Joseph-Salisbury, 2020; Wallace, 2020; Tereshchenko et al., 2022; Education Support, 2023). When workplace cultures fail to provide adequate support or representation, even the most committed teachers may begin to question their place in the profession.

3. Progression to senior leadership

The study found teachers from an Asian or Black ethnic background are significantly more likely to intend to apply for promotions than their White counterparts, even when controlling for differences in other characteristics. Despite this ambition, they remain underrepresented in middle and senior leadership roles.

School leaders that we spoke to highlighted systemic shortcomings in institutional support and mentorship as significant barriers to leadership progression. They noted that while teachers from ethnic minority backgrounds often show strong aspirations and ambition, these are not adequately met with the guidance, encouragement or structured opportunities needed to progress. Recurring challenges included limited mentorship opportunities, a lack of visible role models and unclear or inequitable promotion pathways. Participants also reported microaggressions and assumptions about their abilities, which can deter them from seeking advancement or push them to leave the profession altogether. Leaders noted in some cases that aspiring leaders from minoritised groups were overlooked for informal leadership opportunities – such as leading a team or project – that often serve as stepping stones to formal promotion.

This highlights the importance of ensuring equity not only in formal processes but also in the day-to-day allocation of developmental experiences.

Implications for practice

Together, the research findings call for systemic action to embed equity across the teacher life cycle, with approaches tailored to and tested in specific contexts. Schools and ITT providers shared examples of the actions that they were taking in four key areas to recruit, retain and promote an ethnically diverse teacher workforce.

- Strengthen recruitment: Review marketing and selection processes to eliminate bias and actively support underrepresented groups. For example, one ITT provider shared that diversifying interview panels improved fairness in candidate assessments. Another ITT provider revised their interview format to include scenario-based questions and advanced briefing for all panel members on inclusive practice. They found that this improved the consistency of assessment and reduced reliance on subjective judgement, particularly for candidates from underrepresented groups.

- Create inclusive cultures: Develop wellbeing strategies that address racialised experiences and foster psychological safety for staff. For example, leaders highlighted coaching as a space where staff could discuss identity-related challenges.

- Support retention: Leaders shared examples of schools that offer flexible PPA (planning, preparation and assessment) time and accommodate family commitments wherever possible.

- Diversify leadership: Ensure transparent and inclusive promotion processes, with leadership development programmes that actively support diverse talent pipelines. School leaders shared examples of coaching, leadership shadowing and promoting leadership training opportunities (internal or external), which provided direct insight into leadership roles and made career progression feel more tangible to aspiring leaders.

Conclusion

Ethnic disparities in England’s teaching profession are not inevitable; they are the result of systems and cultures that can and must change. This research provides robust evidence of the scale and drivers of disparities and offers practical insights for schools, trusts and ITT providers committed to addressing them. The challenge is to move this commitment from isolated examples to widespread practice. Crucially, leaders must create space for honest conversations about race and leadership, supported by professional learning that addresses bias and systemic barriers.

A representative teaching profession is not just a matter of fairness; it is essential to the strength, sustainability and integrity of the education system.