Culture as a catalyst for curricular development

Lekha Sharma, Avanti Schools Trust, UK

Curriculum leaders are school administrators who are both instructional leaders and change agents. This model encompasses multiple responsibilities, including enhancing knowledge, subject knowledge expertise and classroom practices to positively impact on curriculum (Glatthorn et al., 2011). Curriculum leadership is complex for many reasons. One of these reasons is that any curricular development work is embedded in a cultural ‘ecosystem’, defined by the sociocultural structures, relationships, norms and interactions within a staff body. Strong school culture, then, is imperative to the work of school improvement (Sharma, 2022). Teacher agency, for example, is not just about individual teachers but rather sits within an ecological approach that recognises the importance of the environmental conditions (Priestley et al., 2015). This school culture very often shapes curriculum development in ways that can’t always be easily articulated or addressed; for leaders, however, this ‘force’ is quite often keenly felt. In their book School Culture Rewired, Steve Gruenert and Todd Whitaker state that ‘leaders have three choices when they discover such a force: they can ignore it, fight it or use it’ (2015, p. 27). School culture, therefore, is a crucial consideration for school leaders when engaging with the complex work of school improvement. School culture as ‘the way we do things around here’ (Deal and Kennedy, 1982, p. 4) offers a useful way of considering this ‘force’ in practice.

Although research in the area of educational leadership is abundant, the strength of the evidence that underpins this research is poor, and there is a lack of strong, causal evidence to back the advice presented to leaders (Coe, 2022). More recent findings synthesising the existing evidence point to the important work that leaders must do to directly influence pupil outcomes. In Coe, Kime and Singleton’s recent leadership evidence review (2022), they conclude that ‘there is good evidence to suggest that the professional environment in schools can affect student learning in a range of ways’ (p. 6) and that the responsibility to create these conditions therefore lies with school leaders.

But creating the optimal conditions is no easy feat. In this article, I will make the case for a combined focus on curricular and cultural development within a school, whereby leaders integrate considerations about school culture within their curricular implementation planning. In doing so, they maximise the success of their curricular development efforts, as well as safeguarding the longevity of these efforts over time.

‘Culture’ has multiple definitions, but for the purposes of this article I will refer to that of Shein (2004, p. 1):

Culture is both a dynamic phenomenon that surrounds us at all times, being constantly enacted and created by our interactions with others and shaped by leadership behaviour, and a set of structures, routines, rules, and norms that guide and constrain behaviour.

This definition is particularly helpful in the context of this article, as it not only highlights the dynamic nature of the phenomenon but also refers to the norms and structures that guide behaviour. From my own experience as a senior leader, leading on curriculum, establishing norms and structures within the curriculum can be incredibly powerful in developing a shared understanding in terms of curriculum delivery. This definition therefore further reinforces the link between curriculum development and school culture development.

The dynamic aspect of school culture that Shein highlights means that not only is it difficult to define and establish the right conditions within our school teams, but it is also difficult to maintain these conditions over time, in the face of changing contextual factors and in service of sustained school improvement.

I offer an alternative conceptualisation as to how curriculum leaders may address this knotty challenge, adapted from Shulman’s (1986) concept of pedagogical content knowledge. This concept ‘goes beyond knowledge of subject matter per se to the dimension of subject matter knowledge for teaching’ (Shulman, 1986, p. 9). Shulman introduced these ideas initially to increase the professional reputation of teaching as a career and to raise the profile of the very difficult task with which teachers are faced. He wanted to highlight the domain-specific knowledge that was required to teach well. But he also wanted to integrate this subject knowledge with the nuanced understanding of pedagogy required for effective instruction.

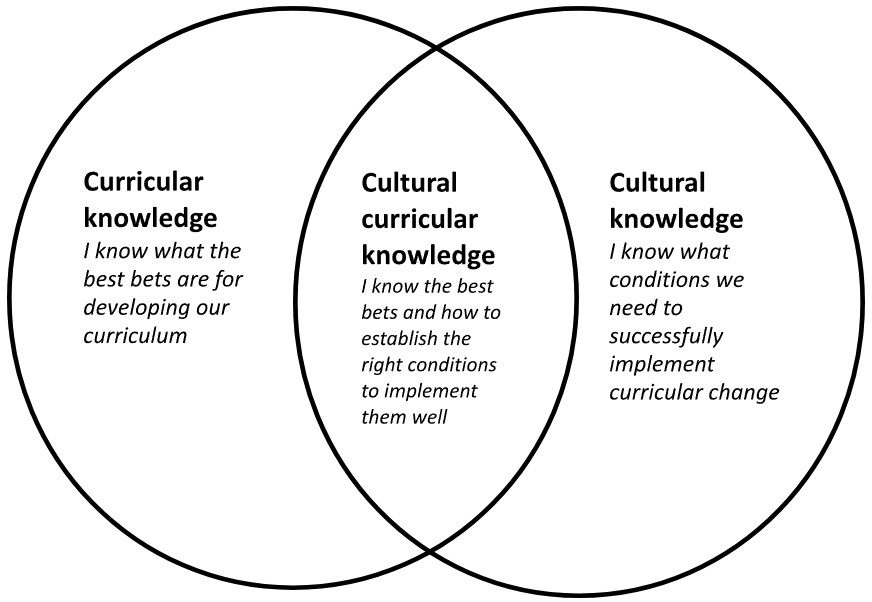

I would argue that curriculum leaders would benefit from considering an alternative integration to that suggested by Shulman: developing the substance of the curriculum and simultaneously developing the conditions in which curriculum evolution takes place, in order to achieve long-term, sustained improvement in quality of education (as represented by Figure 1). Cultural curricular knowledge is the knowledge of these two individual strands, possessed by leaders, woven together to maximise implementation efforts within a school setting.

Figure 2: Cultural curricular model

By considering these two elements of school improvement – the environmental conditions comprising the culture of the school and the specific curriculum development required within the school context – I would argue that leaders are able to pave a path of curricular development that considers the cultural barriers and opportunities that may present themselves, and therefore maximises the chances of successful and sustained improvement over time.

Actionable insights

To exemplify this simultaneous consideration, I offer a short vignette from my own personal experience as a senior leader leading on curriculum in a primary school in South London.

In introducing a refined curriculum to a two-form-entry primary school, we as a senior leadership had a challenge on our hands. The school had experienced significant disruption over a period of years, with multiple headteachers coming and going and high mobility within the staff body. This had led to a culture of uncertainty, a lack of clarity in terms of purpose and direction of travel, and inconsistent ideas around what the expectation of staff was. Multiple versions of the curriculum had been applied over the years and there was, unsurprisingly, a trail of curricular resources and programmes of variable quality left behind, leading to an incoherent and disjointed offer.

We had two priorities of equal importance: 1) to establish a clear and consistent culture within the school that would act as a catalyst for curricular development, and 2) to establish, with absolute clarity, a refined curricular offer that was rooted in evidence-informed practice.

In order to achieve this dual focus, the leadership team decided to initially focus on three areas as part of their implementation planning:

- establishing curriculum principles

- creating the right conditions and norms to catalyse the curricular implementation

- wellbeing and staff satisfaction.

Establishing curriculum principles

Curriculum principles refer to the ‘golden threads’ that define and structure a curriculum offer (Sharma, 2020). By deciding on and defining these, we were able to create a shared and collective understanding around what the curriculum offer was and why these golden threads were being prioritised. This would avoid overcomplication of the curriculum provision and allow teachers to clearly see the underlying curricular architecture, thus maximising the chances of fidelity in terms of curriculum delivery. If teachers knew why the curriculum needed to be delivered in sequence, for example, they were more likely to deliver it in this way. This would have important implications for curriculum coherence but also in addressing the gaps in pupil knowledge that were a result of multiple approaches to curriculum over time. By engaging in professional dialogue with staff around these curriculum principles, the team were able to establish not only the substance of the curriculum offer but also a culture of purpose – why things were being done in the way that they were – when it came to curriculum delivery.

Creating the right conditions and norms

The lack of clarity around ‘how we do things around here’ had led to a sense of inertia in the team. Due to multiple approaches being implemented repeatedly over time, teachers were unsure about the processes and structures that underpinned curriculum delivery, such as planning or tracking pupil progress. In order to address this, we decided to create a curriculum handbook that would act as a reference point for all members of staff around how to make the jump from curriculum to classroom. Leaders worked with teachers in developing the handbook, capturing the most effective practices with which the team had already engaged, to establish a sense of familiarity and to avoid throwing out all that had gone before. These were then refined over time, in collaboration with teachers, to reflect the tweaks that were being ironed out during the implementation process. In undergoing this process, leaders were aiming to create a culture of high expectations and of collaboration, where staff felt actively involved in school improvement, while leaders were able to create high expectations around curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, informed by their domain-specific expertise.

Wellbeing and staff satisfaction

Wellbeing and staff satisfaction were of crucial importance to the school improvement that the senior leadership team was trying to drive. Due to the historic turbulence in school leadership, staff morale was low, and we recognised this not only as a significant barrier to curriculum development but also as a moral obligation to address. In order to begin to address this, the senior leadership team met individually with all members of staff to ensure that all staff’s perspectives and thoughts were heard. In doing so, the leadership team wanted to establish a sense of psychological safety – the ability for staff to feel that they were able to openly share their thoughts and feelings, without fear of repercussions. After we had these 1:1 conversations, the leadership team identified common themes in feedback so that they could respond appropriately to key challenges that staff were facing on the ground.

Conclusion

The vignette above exemplifies how a senior leadership team may deploy cultural curricular knowledge as part of their school improvement efforts and implementation planning. In conclusion, this process is a complex one that is influenced by multiple factors. However, by maintaining a combined focus on the development of the right conditions within the team and the school improvement work at hand, leaders can maximise their abilities to influence positive outcomes ‘on the ground’ in the classroom. The lived experience of applying this combined focus is important to note – in doing so, we as leaders dedicated significant resources in terms of time and investment in staff’s professional learning. It wasn’t as simple as just considering the school culture when implementing curricular innovations. Rather, these considerations around school culture had to be baked into the implementation planning from the very beginning and maintained throughout the implementation process.

Shein refers to the idea of culture being ‘constantly enacted and created by our interactions with others’ (2004, p. 1), which was at the very heart of the above vignette and the concept of ‘cultural curricular knowledge’. Within these small interactions and with repeated revisiting of the structure and norms of the team, as well as the structures and norms associated with curriculum development, leaders can slowly build a culture of purpose, continuous improvement and conversation. This as a process requires detailed exploration of professional development, feedback mechanisms and evaluation, but I offer the concept of cultural curricular knowledge for consideration as a potentially useful starting point for leaders in grappling with the challenges and multi-faceted nature of school improvement.

- Coe R (2022) School environment and leadership: Evidence review: Methodological challenges in school leadership research. Evidence Based Education. Available at: https://2366135.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/2366135/SEL%20Reports/2.%20Methodological%20challenges%20in%20school%20leadership%20research.pdf?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fevidencebased.education%2F (accessed 30 November 2023).

- Coe R, Kime S and Singleton D (2022) School environment and leadership: Evidence review: A model for school environment and leadership. Evidence Based Education. Available at: https://2366135.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/2366135/SEL%20Reports/1.%20A%20model%20for%20school%20environment%20and%20leadership.pdf?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fevidencebased.education%2F (accessed 30 November 2023).

- Deal T and Kennedy A (1982) Organization Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Organization Life. Reading: Addison Wesley.

- Glatthorn AA (1987) Curriculum Leadership. ERIC. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/ fulltext/ ED278176.pdf (accessed 13 December 2023).

- Gruenert S and Whitaker T (2015) School Culture Rewired: How to Define, Assess, and Transform It. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

- Priestley M, Biesta GJJ and Robinson S (2015) Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational Culture and Leadership. Germany: Wiley.

- Sharma L (2020) Curriculum to Classroom. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational.

- Sharma L (2022) Building Culture. Woodbridge: John Catt Educational.

- Shulman LS (1986) Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher 15(2): 4–14.