An international spotlight is now shining on evidence-informed practice. In a fast-changing world, where diverse groups of pupils need to be prepared for their future rather than their parents’ past, the nature of teacher professionalism has changed. This now includes teachers having the confidence to access and/or create the knowledge they need with colleagues and share it to benefit others as well as themselves (Schleicher, 2015). Being evidence-informed is therefore at the heart of teacher professionalism. So why doesn’t everyone just get on with it? Here, I pose five challenges that need addressing before this vision can be realised; I offer thoughts on ways to tackle these, and then conclude by raising questions as a stimulus for conversation.

Challenge 1:

Thinking too narrowly about ‘evidence’

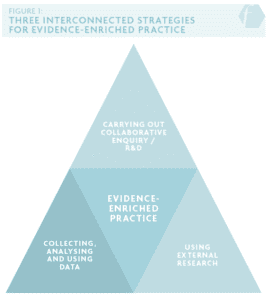

People have different conceptions about ‘evidence’ (Coldwell et al., forthcoming). Some practitioners think about their own or their colleagues’ practice, including pupils’ reactions, while others only accept evidence that incorporates statistical effect sizes that demonstrate the link between a classroom intervention (for example, mastery learning) and externally-assessed pupil progress. For me, evidence-informed practice involves using and promoting a thoughtful blend of three forms of evidence gathering.

External research – while effect-size research is a valid form of research, this type of research is not usually linked to wider outcomes, such as creativity, resilience, etc. Research also exists on how children and young people learn, for example, motivation, the social nature of learning, etc. and the implications for creating appropriate learning environments. Then there is research on professional learning, bringing about change, leadership, schools as learning communities, all of which is relevant when using evidence to enhance practice.

Different kinds of data – this includes a range of pupil data, going well beyond what’s usually assessed, to include, for example, critical thinking, entrepreneurship and wellbeing; data on teachers and teaching, school leadership and the school as a place to learn and develop; and looking at different forms of assessment, such as portfolios, observations, surveys and interviewing pupils. Evidence-informed practice uses data at the start (as a baseline), throughout (to evaluate processes) and at the end (to evaluate impact).

Collaborative enquiry and research and development (R&D) – these are forms of research that include cycles of investigating practice, exploring, trialling and carefully evaluating new practices. These forms frequently incorporate the other two.

Challenge 2:

Being ‘driven’ by evidence

A read of policy documents highlights the interchangeable use of two terms: ‘evidence-based’ and ‘evidence-informed’. The distinction is important. If teaching is ‘evidence-informed’ rather than ‘evidence-based’, teachers are in the driving seat, not the evidence. This fits with another important feature of teacher professionalism – autonomy. Like their pupils, teachers aren’t empty vessels waiting to be filled up. They bring prior knowledge, experience and understanding of their context. Teachers need the confidence and skills to connect what they already know with the different evidence forms and use this to make wise decisions about ways to develop their practice. Think about it this way – evidence isn’t just informing teachers’ practice; it’s enriching it. If we assume that much practice is good anyway, the idea of using evidence and related enquiry processes is that they can add something valuable, helping teachers to think about and try out ways to make practice more powerful (see Figure 1).

Challenge 3:

Risking your own practice being challenged

Engaging in evidence-informed practice can be risky. It may seem easier to ignore problems, not to try to find out why things aren’t working, or to just keep doing the same things rather than get out of your comfort zone and try something different. Evidence-informed practice invariably throws up challenges that force teachers to question their assumptions about the best ways pupils learn. That’s good, because professional learning should challenge assumptions as part of changing practice (Stoll et al., 2012), and evidence-informed practice is a form of professional learning. But you need a steady nerve; taking it seriously requires an enquiry habit of mind (Earl and Katz, 2006) – being open, keen and willing to keep exploring and evaluating the best ways to support pupils’ learning, development, progress and achievement in their context. It also requires a commitment to learning new skills, developing new teaching strategies as necessary, and practising them deliberately to develop expertise (Stobart, 2014). Unquestionably, evidence-informed practice isn’t about standing still.

Challenge 4:

Convincing others about the value of evidence-informed practice

I assume (or at least hope) that most readers are interested in evidence-informed (or evidence-enriched) practice, if not passionate about its merits. But you will no doubt know

I assume (or at least hope) that most readers are interested in evidence-informed (or evidence-enriched) practice, if not passionate about its merits. But you will no doubt know

colleagues who are not similarly predisposed, including some who are downright sceptical or resistant. Persuading yourself to invest the energy and take the associated risk of practice change is one thing; convincing others is altogether different. Language is important here. I used the term ‘evidence-enriched’. It may be a matter of taste, but when introducing initiatives, it can help to suggest that colleagues will be building on strengths. Given already considerable workloads, some people will want persuading that evidence-informed practice ‘works’ – they’ll only be convinced by evidence. Designing small projects with other interested volunteers and then sharing the findings – especially quick wins and other successes, but also what you’ve learnt not to do – is commonly used to build up support and move towards the point where many colleagues are engaged.

For readers who are senior leaders (especially head teachers/principals), your interest in and commitment to evidence-informed practice is critical. In all my research, evaluation and R&D projects, where the head teacher has seriously ‘bought in’ to understanding evidence-informed practice, using evidence and backing colleagues doing so, efforts to develop a culture of enquiry and related practice throughout the school have been more successful. These head teachers ensure the conditions in schools that enable other colleagues to become fully engaged and follow through – for example: time, access to research resources, opportunities for knowledge-exchange, modelling being evidence-passionate (by reading themselves, for example) and testing out their own theories of action about what they expect from particular interventions, nurturing evidence champions, networking and connecting with critical friends and research partners (Stoll, 2015).

Challenge 5:

Going it alone

It may be evident from what has gone before that I see evidence-informed practice as a collaborative endeavour. Considerable international research now exists highlighting the importance of collaboration, social learning and collective learning. Autonomy within professionalism today is much more about collective agency (can do) and responsibility (accountability to peers) (OECD, 2016a). And a third, related feature of teacher professionalism these days is peer networking – collaborating with colleagues within and across schools. I wouldn’t want to prevent any individual who is keen from carrying out a piece of enquiry with their own pupils – that’s great – but I just think more broadly about what it could be like if a whole system was evidence-informed. I know that there are examples of schools that are learning organisations (OECD, 2016b), where teachers connect with colleagues in their school and others to carry out evidence-rich collaborative enquiry, to learn together and find creative and compelling ways of sharing findings and moving knowledge about evidence-informed practice around the system. But there’s a way to go yet if this is to become systemic and sustainable.

Conclusion

Enriching your practice with evidence can be satisfying and fruitful, but also challenging. These challenges are worth embracing, but they aren’t easy to address, and I’m sure there are others that I haven’t discussed. Here are a couple of questions as conversation starters:

Do you face any, or all, of these challenges? How are you addressing them? What else might you do?

What other challenges to evidence-informed practice can you think of? How will you tackle these?

References

Coldwell M, Greany T, Higgins S, Brown C, Maxwell B, Stiell B, Stoll L, Willis B and Burns H (Forthcoming) Evidence-Informed Teaching: An Evaluation of Progress in England. Report for The Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England.

Earl L and Katz S (2006) Leading Schools in a Data-Rich World: Harnessing Data for School Improvement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

OECD (2016a) Supporting Teacher Professionalism: Insights from TALIS 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264248601-en.

OECD (2016b) What Makes a School a Learning Organization: A Guide for Policy Makers, School Leaders and Teachers. Paris: OECD publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/school-learningorganisation.pdf

Schleicher A (2015) Schools for 21st-Century Learners: Strong Leaders, Confident Teachers, Innovative Approaches. International Summit on the Teaching Profession. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264231191-en.

Stobart G (2014) The Expert Learner: Challenging the Myth of Ability. Maidenhead: Open university Press.

Stoll L (2015) Using evidence, learning and the role of professional learning communities. In Brown C (ed) Leading Evidence Use in Schools. London: IOE Press.

Stoll L, Harris A and Handscomb G (2012) Great professional development which leads to great pedagogy: nine claims from research. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

A useful read that highlights potential issues and problems. These can be noted and taken into account when planning for evidence-informed practice.