Skilful questioning: The beating heart of good pedagogy

The issue that teachers face

Questions are an integral part of classroom life and essential to every teacher’s pedagogical repertoire. They are also one of the elements of effective formative assessment (Black et al., 2003). Questioning serves many purposes: it engages students in the learning process and provides opportunities for students to ask questions themselves. It challenges levels of thinking and informs whether students are ready to progress with their learning. Questions that probe for deeper meaning foster critical thinking skills and higher-order capabilities such as problem solving, and encourage the types of flexible learners and critical thinkers needed in the 21st century.

Questioning is a crucial pedagogical skill, but one that requires practised knowledge (Cavanaugh and Warwick, 2001). Paramore (2017) identifies an imbalance of questions often found in teaching, saying there is a dominance of teacher talk and an over-reliance on closed questions, providing only limited assessment for learningKnown as AfL for short, and also known as formative assessment, this is the process of gathering evidence through assessment to inform and support next steps for a students’ teaching and learning (AfLAssessment for Learning (also known as formative assessment) - the process of gathering evidence through assessment to inform and support next steps for a students’ teaching and learning) information for a teacher. The issue then is how classroom questioning strategies can become more effective, as evidence suggests that teachers ask too many questions and too many of these questions are low level.

What the research says

The value of classroom questioning is well documented. Research tends to focus on the relationship between teachers’ questions and student achievement; here are some of the important messages.

Types of questions used

Too often, questions from teachers are organisational, such as ‘What do we always put at the top of our page to begin with?’ or instructional in nature, such as ‘Who can tell me what an adjective is?’ and fail to develop deep learning. Wragg’s early study (1993) found teachers commonly use three types of question:

1. Management-related, e.g. ‘Has everyone finished this piece of work now?’

2. Information recall-related, e.g. ‘How many sides does a quadrilateral have?’

3. Higher-order questions, e.g. ‘What evidence do you have for saying that?’

In Wragg’s study, 57 per cent of questions were management related, 37 per cent required information recall and only 8 per cent challenged higher-order thinking.

Closed or convergent questions have low cognitive involvement and result in limited answers such as ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Open or divergent questions encourage greater expansion in answers and promote better classroom dialogue (Tofade, Elsner and Haines, 2013). Closed questions are still important, however, and help assist in knowledge retrieval; but proceed with caution here, as the inevitable one-word student answers limit classroom dialogue resulting in what Alexander called ‘cognitively restricting rituals’ (2006: p.14). Lower-attaining students benefit from closed questions, allowing them greater accuracy of response which in turn breeds encouragement, while higher-attaining students respond better to more challenging questions (Woolfolk, 2008). In order to maximise AfL in lessons, use different types of questions but limit the procedural and emphasise questions that centre on learning, and differentiate them to maximise AfL.

Timing

Student wait time (giving a brief period of time for students to think or reflect before answering) has a positive effect on learning. Brooks and Brooks (2001) found that a rapid-fire questioning approach fails to provide teachers with accurate information about student understanding. Typically, the time between asking a question and a student’s response is about one second. Cohen et al. (2004) recommend wait times of three to five seconds for closed questions and up to 15 seconds for open-ended questions.

Cognitive levels

Complex questions promote complex thinking, argue researchers Degener and Berne (2016). But is it really that simple? There is a lack of consensus in the literature. Some researchers have found higher-cognitive questions superior to lower ones while others have not. In general, the level of teachers’ questions is low. Around 60 per cent of questions expect only factual information from students (Lee and Kinzie, 2012). Samson et al. (1987) found that higher-cognitive questioning strategies have a positive effect on learning, but this was not as large as has been previously suggested. Simply asking higher-cognitive questions does not necessarily produce higher-cognitive responses from students.

On balance, low-level questioning aimed at recall and fundamental-level comprehension will plateau classroom learning quickly. Higher-level questions can produce deeper learning and thinking, but a balance needs to be struck. Both have a place and a mixture of questions is recommended.

Effective approaches

Over the years, classification taxonomies have been developed to guide teacher questioning (see Krathwohl (1964); Wilen (1986) and Morgan and Saxton (1991) as early examples). Hannel and Hannel’s ‘highly effective questioning method’ (2005) shows how teacher questions promote student engagement, and an interesting approach is the ‘sequences of teacher and student questions’ (Dekker-Groen, 2015). In literacy, Degener and Berne (2016) devised their six-level ‘continuum of questioning complexity’ to offer increased challenge at each cognitive level. Shirley Clarke’s website (www.shirleyclarke-education.org) has a wide range of practical resources on AfL and proven questioning strategies.

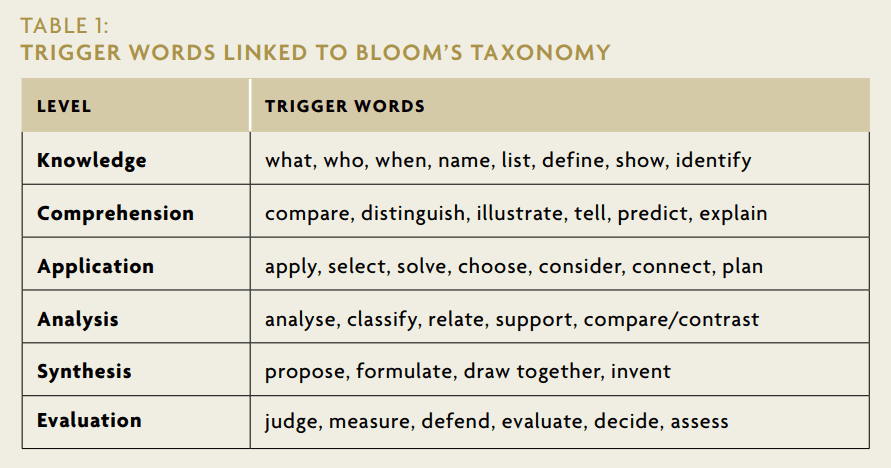

Perhaps the most well-known questioning framework is Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy (1956), later revised by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). In this six-level hierarchy, lower-order questions gauge comprehension; medium-level gauge knowledge application, and higher-order questioning elicits synthesis, analysis and evaluation.

Knowledge

‘Can you remember…?’

Comprehension

‘Tell me how this works…’

Application

‘Where else have you seen this pattern?’_

Analysis

‘Explain to me what is happening here?’

Synthesis

‘What conclusions can you draw from this?’

Evaluation

‘Can you measure how effective this is?’

Trigger words are an effective way to formulate questions, as shown in Table 1.

Ideas to try in the classroom

There are many questioning tactics to choose from to promote learning and provide excellent formative assessment information:

1. No hands up. Anyone can answer, which avoids the same few students answering questions.

2. In the hot seat. Students take it in turns to sit in the ‘hot seat’ and answer questions.

3. Ask the expert. The teacher puts questions to a student on a given topic, extending this to encourage other students to ask questions.

4. Ask the classroom. The teacher displays a number of written questions to stimulate thinking about pictures or objects in the classroom.

5. Think-pair-share. Allows time to share ideas with a partner and respond to a posed question.

6. Phone a friend. A useful strategy in which a student nominates another to answer the teacher’s question. The first student also provides an answer.

7. Eavesdropping. When groups are working, the teacher circulates around the classroom and poses questions to groups based on what is heard in their discussions.

8. Question box. An actual box has a series of questions in it devised by the teacher. Time is set aside at the end of a week to choose some to discuss as a class.

9. Here is the answer, what is the question? Deliberately back to front to encourage out-of-the-box thinking.

10. More than me. The teacher asks a student a question and deliberately cuts short the answer to involve another student to build on this answer.

Things to take into account

‘It is better to have a classroom full of unanswered questions than unanswered answers’ (Morgan and Saxton, 1991).

Good questions develop discussion and invite exploration. Poor questions can stifle and put undue pressure on students. Using a variety of question types to inform your assessment can transform your classroom into a ‘questioning classroom’. A classroom ethos and organisation with enquiry at its heart is an effective one, where purposeful talk dominates and teachers ask fewer questions. Dialogic teachingThe effective use of talk for teaching and learning, involving ongoing talk between teachers and students (Alexander, 2017) uses skilled questions to extend thinking where answers to teachers’ questions are built on rather than merely received. Dialogue allows a teacher to respond to students’ answers and if necessary re-orientate them. Exchanges chain together, feedback from questions leads thinking forward and students’ answers are extended. Questions are among the most powerful teaching tools we have and adopting best practices will significantly enhance the quality of teaching and learning.

Questions to reflect on/discuss

- Is my classroom a ‘questioning classroom’?

- Does talk permeate my teaching and learning approach?

- What types of questions and how many questions do I typically ask in my teaching?

- Do the questions I ask target higher-order thinking and raise the cognitive stakes? Is this true of my teaching across all subjects?

Further reading

Excellent website with many resources to embed AfL and effective questioning in classrooms: Available at www.shirleyclarke-education.org.

Chapter 2, Questioning to learn, is very readable: Fisher R (2005) Teaching Children to Learn. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes.

Practical and clear overview of Bloom’s taxonomy: West Lothian Council Educational Psychology Service. Questioning. Raising Attainment sheet 1. Available at: www.westlothian.gov.uk/education.

References

Alexander RJ (2006) Towards Dialogic teaching: rethinking classroom talk. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Dialogos.

Alexander RJ (2017) Towards Dialogic Teaching: rethinking classroom talk. 5th ed. Cambridge: Dialogos.

Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Airasian PW, Cruikshank KA, et al. (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: Longman.

Black P, Harrison C, Lee C, Marshall B and Wiliam D (2003) Assessment for Learning: Putting it into Practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Bloom BS (ed.) (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Company, Inc.

Brooks, JG and Brooks MG (2001) Becoming a constructivist teacher. In: Costa: AL (ed.), Developing Minds: A Resource Book for Teaching Thinking (pp.150–157). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Cavanaugh MP and Warwick C (2001) Questioning is an art. Language Arts Journal of Michigan 17 (2): 35–38.

Cohen L, Manion L, and Morrison K (2004) A Guide to Teaching Practice. London: Routledge.

Degener S and Berne J (2016) Complex questions promote complex thinking. The Reading Teacher 70 (5): 595–599. International Literacy Association.

Dekker-Groen A, Van der Schaaf M and Stokking K (2015) Teachers’ questions and responses during teacher-student feedback dialogues. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 59(2).

Hannel GI and Hannel L (2005) Highly effective questioning 4th ed. Phoenix AZ: Hannel Educational Consulting.

Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS and Masia BB (eds) (1964) Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: The affective domain. New York: McKay.

Lee Y and Kinzie MB (2012) Teacher question and student response with regard to cognition and language use. Instructional Science: An International Journal of the Learning Sciences 40(6): 857–874.

Morgan N and Saxton J (1991) Teaching Questioning and Learning. New York: Routledge.

Paramore J (2017) Questioning to stimulate dialogue. In: Paige R, Lambert S and Geeson R (eds) Building skills for Effective Primary Teaching. London: Learning Matters.

Samson GK, Strykowski B, Weinstein T and Walberg HJ (1987) The effects of teacher questioning levels on student achievement. The Journal of Educational Research 80(5): 290–295.

Tofade TS, Elsner JL and Haines ST (2013) Best practice strategies for effective use of questions as a teaching tool. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 77 (7) Article 155.

Wilen WW (1986) Questioning skills, for teachers. Washington DC: National Education Association.

Woolfolk A, Hughes M and Walkup V (2008) Psychology in Education. Harlow: Pearson.

Wragg EC (1993) Questioning in the Primary Classroom. London: Routledge.

This article was published in July 2017 and reflects the terminology and understanding of research and evidence in use at the time. Some terms and conclusions may no longer align with current standards. We encourage readers to approach the content with an understanding of this context.