A pedagogy of professional noticing and co-inquiry: Embedding drama for oracy across the primary curriculum

- Curriculum |

- Drama |

- Oracy

LISA STEPHENSON AND RACHEL LOFTHOUSE, CARNEGIE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, LEEDS BECKETT UNIVERSITY, UK

Introduction

Oral language skills underpin children’s educational success and enhance positive cognitive, social, emotional and life outcomes. However, significant numbers of children struggle to develop competence in speaking and listening, especially children from areas of high economic deprivation (Dobinson and Dockrell, 2021). This is highlighted by the Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Policy Group (APPG), whose reports are advocating a renewed focus on oracy (2020).

This case study shares the emerging findings from year one of a two-year project, funded by the Paul Hamlyn Teacher Development Fund. We are utilising drama pedagogy to bring the curriculum to life through storytelling, with an explicit focus on children’s oracy. The project is co-led by research and practice experts in drama pedagogy (Stephenson, 2022) from the Story Makers Company, Leeds Beckett University and school leaders from Bowling Park Primary. The eight partner schools are in the Bradford BD5 school’s network, and share an ambition to embed an integrated story approach to curriculum. Our focus is on embedding drama pedagogy within the humanities subjects, creating an imaginative story curriculum experience in Years 3 and 4 across the schools. As part of this knowledge exchange, teachers are paired with one of five artist educators (specialists in drama pedagogy) and given time and space to co-plan, co-deliver and co-reflect for 15 sessions across each year. Central to this process of professional development and learning (CPDL) is a coaching approach (Lofthouse, 2019), blended with expert pedagogical modelling and learning exchange. This article explores the ways in which our co-inquiry approach to CPDL was integral to supporting more sustainable pedagogical changes in the localised contexts of the schools involved.

Educational landscape: Context and ambition

The eight partnership schools are situated in an economically deprived area of inner-city Bradford. Their 3,800 children come from a diverse range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The schools have very strong ties to the local community and were keen bring this experience to the project, ensuring that it remained culturally relevant to their children’s lived experiences. Many of the children start in Early Years with social and language skills well below national expectations, and a large majority of pupils speak English as an additional language (EAL). Additionally, some are ‘new to English’, coming from the Czech Republic or Slovakia, and some of these are from Gypsy or Roma backgrounds. The schools noted a significant impact on learner’s oracy and communications skills following COVID-19 (Lander et al, 2022) and they were not alone. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Oracy (APPG) reported that school closures had a detrimental effect on the spoken language of their most disadvantaged pupils.

Embedding oracy: Why drama pedagogy?

Initially, senior leaders across the schools discussed the need for a ‘collaborative brave space’ to make new informed pedagogical choices through engagement in creative pedagogies that would impact on pupils’ social mobility (Cultural Alliance, 2019). The term ‘brave space’ recognises that our pedagogical approach initially ‘felt risky’ because many were unsure about how it would integrate with curriculum requirements. Our model of CPDL was therefore critical in empowering teachers to activate curriculum content from a different pedagogical starting point.

Drama, expressive arts and story have a unique way of activating emotion and action. The project uses drama pedagogy, and not ‘teaching drama’. In drama pedagogy or ‘drama worldbuilding’ (Stephenson, 2022), children co-create stories with elements of active social problem-solving alongside teachers and artists. Within these fictional contexts, they are challenged to work collectively, coming up with ideas that draw from their diverse perspectives. A topic about the Maya can become a story about friendship or competing values, as well as covering historical content. This means that they are actively applying curriculum content, such as geographical or history topics, using a range of inquiry and communication skills that foreground oracy and relationships. For some children, such those from Roma backgrounds, storytelling draws from their cultural literacy practices more than writing and text. The pedagogy involves making meaning through linguistic, visual, audio and spatial modes of communication – this is effective for EAL learners and has been shown to improve spontaneity, fluency, articulation, vocabulary and the use of diverse language registers (O’Toole and Stinson, 2013). However, like most creative pedagogies, it can be difficult to ‘evidence’. Research-informed expertise in the pedagogy was therefore critical to embedding high-quality learning.

Professional development as a pedagogy of noticing through co-inquiry

The rhythm of the CPDL model has been key in holding space for co-creation, co-planning and co-reflection and driving the project. This action research cycle has provided sustained time and space for teachers and artists to take professional ownership, embedding practices at their own pace in a non-judgmental community of practice. Each term begins and ends with professional practice days, where pedagogy is modelled and shared across schools. This process is underpinned by three main inquiry questions,

- Why does this pedagogical approach matter to us and our children?

- How does drama/creative pedagogy work in our classrooms/schools/curriculum?

- What is the impact of this pedagogy on teaching and learning?

Our process is outlined through six principles of co-inquiry across the year:

- establishing a shared set of pedagogical values

- creating a shared language that draws from empirical research

- experiencing the pedagogy in action as participants

- co-reflecting and co-planning in response to shared practice

- sharing localised approaches to embedding learning

- co-researching to build practice-based research in response to emerging challenges.

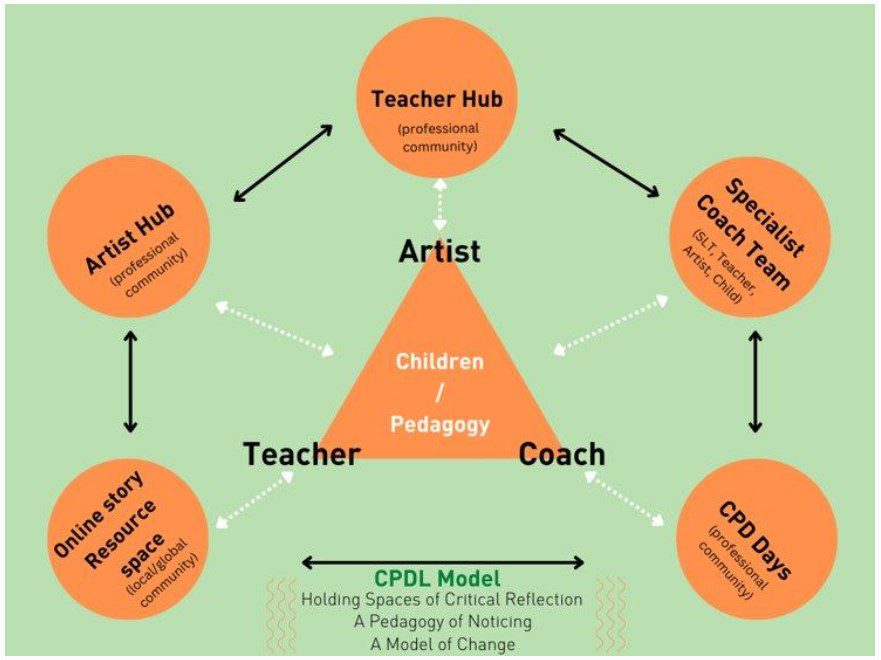

Following each co-taught session in school, artist, teacher and coach also have a reflective conversation. The five coaches have a range of professional experiences as SLT, teachers and artists, with the coaching providing diverse perspectives. Termly online coach meetings are used to feed back across schools, providing a strong feedforward loop from which to address tensions and needs within the project on CPD days. Our model of CPDL is outlined in Figure 1. We view this integrated coaching partnership as relational and dialogic (Lofthouse, 2019), meaning that professional practice is co-created through sustained co-inquiry.

Figure 1: A pedagogy of noticing through co-inquiry

In all coaching and professional development sessions across the project, we asked teachers and artists to co-reflect on the significant moments that they noticed within sessions. Rooney and Boud (2019) note that professional noticing is essential for developing professional practice. It is an intentional activity embedded in observing and performing professional practice, providing shared dialogue and meaning making.

Emerging findings

At the midpoint of the project, we interviewed 20 teachers and five artists across all schools. Each school pairing was invited to critically reflect on the project so far through the following questions:

- What is a significant moment that stands out for you so far in the project?

- What did you notice about how the drama worked in pursuit of the learning?

- What did you notice about pupil engagement in the session?

- How did the pupils make meaning during the session?

- How was oracy activated by the drama?

- Is there anything new that you noticed about your practice within the session?

- What would you like to take forward and build on in the next session?

Differing teacher responses have been thematically analysed below and indicate that teachers are noticing learning in new ways in relation to their own professional development and the impact on pupils.

Time and space for reimagining pedagogical approaches

Teachers initially reflected on the importance of professional trust in trying new pedagogies. This initially involved relinquishing a sense of power and control and having time for observation.

It’s a different approach to teaching. I think if I was in the classroom I might not have let go of the control as easily as I did in the different space that we were using.

I think with the teacher head on it was quite tricky trying to make that decision, because as a teacher you plan your lessons, and you know how you want the lessons to sort of go and what you want out of the children.

Meaningful pupil investment

Many of the teachers’ reflections involved noticing pupil investment in new ways. Investment was related to increased confidence in expression, active engagement in sessions and stronger friendships.

It was quite difficult at the start, but then I thought “yes, this is going to work” because they were just so enthusiastic and all they kept talking about is “that‘s my building”. They‘re coming up with words like “the walls will never melt”, “it‘s got steel” and yes, they were just so invested in it and then some of them went home to research, didn‘t they?

Pupil investment was also linked to extending learning from home to school and a greater sense of inquiry and exploratory questioning from children.

He doesn’t engage at playtime with anybody. He doesn‘t interact socially. After we‘d done the wise man and he’d got a bit of confidence to speak out, he was actually interacting at playtime and playing games with the other children. He found his voice in the session but then carried it on further in the rest of his school life.

Challenging impact on pupil learning

Teachers often recounted aspects of learning that surprised them. These often related to the impact on learning, such as use of higher-order vocabulary, social and emotional engagement, use of a range of language registers and non-verbal communication, which challenged their perceptions of what they felt some children were capable of.

Yes, I think it allows opportunities for children who perhaps, like you say, struggle in the classroom setting, to be celebrated and to be successful. I think it also gives us as teachers a bit more headspace and time to look at that in a different context where you’re not so wrapped up in worrying about leading lessons and the complications that comes with that. You’re able to observe children in a different way.

Teachers observed that children linked the story worlds to their lived experiences, and that many of their questions were related to social justice – this fueled meaningful dialogic inquiry and agentic learning.

No. I’d say for me it was quite unique and I think the way that they actually pictured the conflict itself and talked about it being heavy was something I hadn’t anticipated that they would be thinking like that.

Discussion: Empowering teachers through dialogic co-inquiry

In relation to oracy, drama pedagogy creates a ‘dialogic space’ (Mercer and Mannion, 2018), where communication in the classroom is collective (teachers and children in partnership). It is ‘reciprocal’ (talking, listening and sharing viewpoints), supportive (no fear of failure), cumulative (builds on each other’s ideas) and purposeful (with educational goals in view). Our CPDL model was underpinned by these principles.

As we continue the project, a new model of the social and emotional aspects of oracy has been developed, based on teachers’ observations of children’s learning, by Stephenson, Patel, and Crowther. This focuses on conflict resolution and wellbeing competencies. Currently, this empirical research (Stephenson, 2022) is being piloted across all schools and developed further as a formative assessment that aims to support teachers and policymakers nationally and internationally and feed into the Oracy APPG work. It will be shared through our project website.

While this project has cost and time implications, its success has relied on sustained investment, commitment and responsive actions from all involved. Insights have emerged from holding spaces for professional noticing over the first year, and are underpinned by empirical research. We were all able to shift our practices through a process of co-inquiry. Critically, the creative pedagogy has impacted positively on pupil learning and relationships, creating a culturally relevant curriculum. More widely, the project highlights the potential of developing meaningful partnerships between schools and universities in order to empower teachers and schools to develop responsive pedagogies to the needs of their learners.

- Cultural Alliance ( 2019) The arts for every child: Why arts education is a social Justice issue. Available at: https://culturallearningalliance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Arts-for-every-child-CLA-Social-justice-briefing.pdf (accessed 30 March 2023).

- Dobinson KL and Dockrell JE (2021) Universal strategies for the improvement of expressive language skills in the primary classroom: A systematic review. First Language 41(5): 527–554.

- Lander V, Holloman TR and Tan J (2022) Collaboratives on addressing racial inequality in COVID Recovery: Education briefing paper. Race Equality Foundation. Available at: www.academia.edu/49241317/Collaboratives_on_Addressing_Racial_Inequality_in_COVID_Recovery_Education_A_Briefing_Paper (accessed 22 March 2023).

- Lofthouse R (2019) Coaching in education: A professional development process in formation. Professional Development in Education 45(1): 33–45.

- Mercer N and Mannion J (2018) Oracy across the Welsh curriculum: A research-based review –key principles and recommendations for teachers. Oracy Cambridge. Available at: https://oracycambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Oracy-across-the-Welsh-curriculum-July-2018.pdf (accessed 22 March 2023).

- Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) (2020) Speak for change: Initial findings and recommendations from the Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group Inquiry. Available at: https://d5119182-bdac-43d5-be55-e817e7736e5b.filesusr.com/ugd/2c80ff_33e3208ce4dd4764b154682488c53ef7.pdf (accessed 22 March 2023).

- O’Toole J and Stinson M (2013) Drama, speaking and listening: The treasure of oracy. In: Anderson M and Dunn J (2013) How drama activates learning: Contemporary Research and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 159–177.

- Rooney D and Boud D (2019) Toward a pedagogy for professional noticing: Learning through observation. Vocations and Learning 12(3): 441–457.

- Stephenson L (2022) Collective creativity and wellbeing dispositions: Children’s perceptions of learning through drama. Thinking Skills and Creativity 47:101188.

About the Author

Rachel Lofthouse is Professor of Teacher Education in the Carnegie School of Education at Leeds Beckett University. Rachel has a specific interest in the link between practice development and professional learning for teachers and educators, based on innovative pedagogies and curriculum design and collaborative practices for coaching and mentoring.

-

This author does not have any more posts.