An education of the head, heart and hand

Liz Robinson and Sarah Seleznyov, Big Education, UK

Big Education is a multi-academy trustAbbreviated to MAT, a group of schools working in collaborat with three schools: Surrey Square, School 360 and School 21. The trust works with a network of over 500 schools across the UK, focusing on developing pupils as empowered and successful individuals, and moving beyond a narrow emphasis on teaching for exam success. We believe that there is a risk of an excessive focus on the type of academic learning needed to pass statutory tests, which leads to other critical learning being minimised or omitted (Greany, 2018). As a result, many schools feel that they need to design their curriculum around what is tested, rather than what young people really need to know and be able to do.

Our trust wants to offer pupils an education of head (academic learning), heart (relationships and wellbeing) and hand (creativity and social activism), and this has provided a tight but loose focus within which to innovate. This is an ‘and’ model, and not an ‘or’ model: it is possible to get strong academic results without teaching to the test. It is possible to focus on knowledge and skills and understanding, and to support pupils to achieve in all three. This approach offers teachers a different kind of teaching experience, in which risk-taking and innovation are encouraged, and this article explores how this has been achieved. The article describes how Big Education schools have been supported to innovate in order to develop teaching and learning approaches that offer a full breadth of learning experiences to pupils in their care, offering three short case studies of how the schools’ practices fulfil this goal.

Key to this undertaking has been the trust’s use of two key tools: the Big Education Diagnostic and design thinking processes.

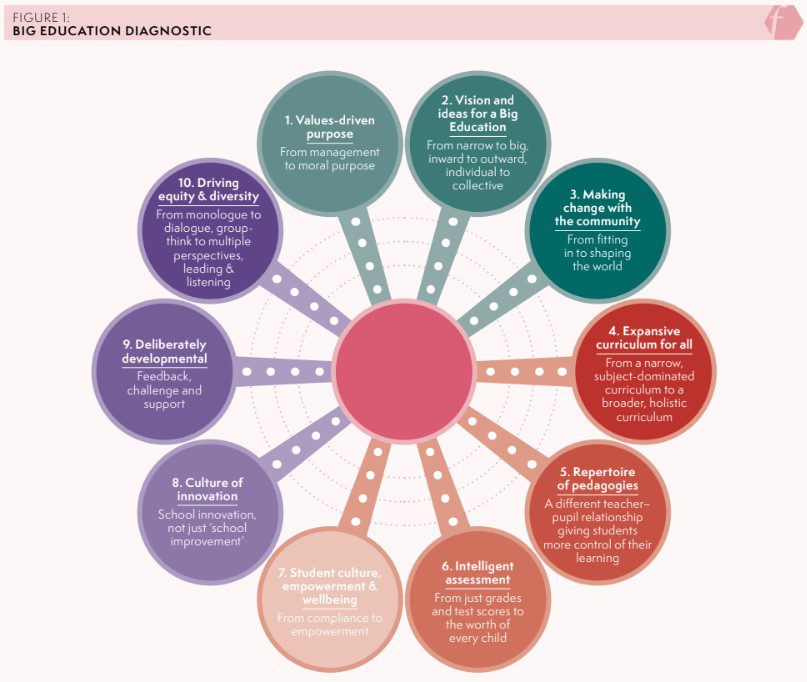

The Diagnostic (Figure 1) offers schools an alternative approach to self-evaluation. Under 10 broad headings, it supports schools to consider what is required to design and implement a curriculum of the head, heart and hand.

Figure 1: Big Education Diagnostic

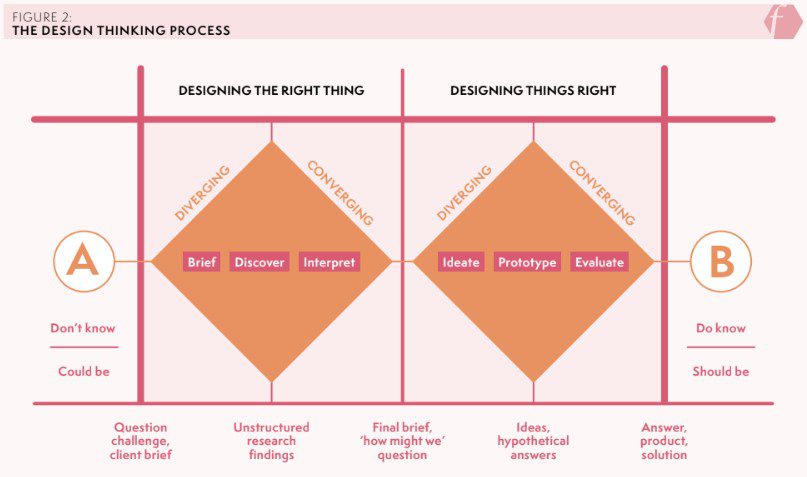

The Diagnostic helps schools to identify their own curriculum strengths and areas for development, so that challenges can be tackled through a process of structured innovation. In order to achieve this, Big Education schools make use of a design thinking process (Brown and Katz, 2019). The ‘double diamond’ methodology (Figure 2) helps schools to understand the challenge, share ideas, develop strategies together and assess and tackle potential risks.

The first stage of the process or ‘diamond’ enables schools to think creatively, ‘horizon scanning’ to draw on what is known (divergent thinking) and then working collaboratively to refine ideas for prototyping (convergent thinking). In this phase, schools develop a deeper understanding of the ‘problem’ that they are seeking to tackle – for example, through conversations with stakeholders or analysis of data – and spend time exploring what is known about the challenge, from their own practices and good practice locally, nationally and beyond. They use this information to plan a change to practice that they would like to test.

In the second stage of the process or ‘diamond’, participants then design the prototype innovation (divergent thinking), subsequently narrowing thinking as they evaluate implementation, analysing evidence of successes and difficulties (convergent thinking). In this phase, the evidence gathered in the first ‘diamond’ is used to carefully plan a change to practice that will be prototyped; plans are made to gather baseline and impact data; and an implementation plan is enacted. In the second half of the ‘diamond’, the success of the prototype is evaluated as it is implemented, through the ongoing collection of impact evidence, in order to make necessary changes to the prototype as it is scaled up and its reach expanded, moving in essence into a third ‘diamond’.

Figure 2: The design thinking process

The above tools have supported each of the three Big Education schools to innovate with rigour and develop their own signature head, heart and hand curriculum practices that move beyond a narrow academic focus on teaching to the test. The following examples detail three different approaches to ensuring this curriculum balance and breadth in different key stages and phases.

School 360As a new school opening in September 2021, we had learnt from the COVID lockdown the importance of play for wellbeing. We felt that English schools formalised too quickly for five-year-olds, so we drew on learning from high-performing Scandinavian and Asian countries and our neighbours in Wales and decided to incorporate play as a core curriculum principle. Key to making this effective was ensuring progression from Reception to Year 2. We did this by:

Studies in Wales found that attainment and wellbeing improved (Taylor et al., 2015) once a play-based curriculum was introduced until age seven, and so did we. As the children became more independent, they became more engaged, wellbeing was high, peer relationships were strong and data showed strong attainment and progression. |

School 21Oracy is the ability to communicate effectively. At School 21, oracy is a moral cause. One of the biggest barriers to young people getting on is a lack of eloquence. Employers put good oral communication at the top of their requirements. Yet we rarely teach it systematically in schools. Our curriculum gives oracy the same status as reading and writing. All teachers at School 21 are oracy teachers. There is an understanding across all subject areas of how talk aids teaching, analysis and higher-order thinking. We developed a framework with Cambridge University, which breaks down oracy into four strands: physical, cognitive, linguistic, and social and emotional. These skills are taught directly, but also shape the way in which other areas of the curriculum are taught:

The success of oracy at School 21 led to the inception of a charity, Voice 21, which now works with 870 schools and 1,900 teachers across the UK to disseminate these practices, offering a variety of tools, programmes and resources to support the curriculum, researching the teaching of oracy and campaigning nationally for it to be embedded within the National Curriculum. |

Surrey SquareLike all Big Education schools, we teach a project-based learning curriculum, in which an essential question shapes a unit of cross-curricular work with a real purpose and a final product. We have developed pupil agency through this approach by enabling pupils to focus on projects that tackle real-life challenges that they face in their community. We draw on approaches like those of Citizens UK, in which problems are locally identified and explored, a network of people who could affect change is mapped, and pupils are taught strategies to engage stakeholders who can make a difference: lobbying, petitioning, demonstrating, writing letters, etc. In one recent project, pupils in Year 5 began a citizenship campaign to tackle the Hostile Environment Policy introduced in 2014. This policy directly affected over 40 children in the school. Pupils were directly involved in the campaigning, working closely with Citizens UK, including visiting the House of Lords to have their voices heard and protesting outside the Royal Courts of Justice. This campaign resulted in a win, as the fees for citizenship applications were found to be unlawful. This community organising project is now an integral part of our curriculum. We want all pupils to learn to be advocates and activists for themselves and others, so that the community feels empowered. |

Conclusion

What can other leaders and teachers learn from our experiences? Firstly, the use of a tool for self-evaluation and school improvement planning – for example, the Big Education Diagnostic – can help to reframe and broaden thinking about the curriculum for pupils, beyond a focus on teaching to pass exams. Secondly, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to curriculum breadth, and the design thinking approach can help schools to innovate with rigour, producing tailored solutions to local challenges and making a real difference to pupil learning.

Our schools’ approach to the curriculum has been designed and implemented within the restraints of ever-dwindling budgets and staffing and without compromising on academic achievement. However, this has not been an easy journey for us: teaching in this way makes different demands on staff, and working within the current accountability framework is challenging. Leaders must ensure that innovations they introduce are sustainable and manageable for staff, and constantly consider workload and wellbeing. Leaders have had to be confident in giving their staff permission to spend less time on test preparation and more time on the education that pupils deserve.

What really motivates school staff to persevere, despite the challenges? The wellbeing and learning of the pupils is visible and school staff are excited to teach. We do not have all the answers, but we are offering pupils a more rounded curriculum experience, and encouraging other schools to join our journey: rethinking practice, challenging mindsets and shaping futures.

- Adey P, Robertson A and Venville G (2002) Effects of a cognitive acceleration programme on Year 1 pupils. British Journal of Educational Psychology 72(1): 1–25.

- Brown T and Katz B (2019) Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. New York: Harper Business.

- Greany T (2018) Hierarchy, markets and networks: Analysing the 'self-improving school-led system’ agenda in England and the implications for schools. UCL IOE Press. Available at: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10053501/1/Hierarchy%20Markets%20and%20Networks%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 26 March 2023).

- Taylor C, Davies R, Rhys M et al. (2015) Evaluating the foundation phase: The outcomes of foundation phase pupils up to 2011/12 (Report 2). Welsh Government. Available at: www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-07/150107-outcomes-foundation-phase-pupils-2011-12-report-2-en.pdf (accessed 26 March 2023).