Creating a fully encompassing curriculum around the purpose of education

What is the purpose of education?

If a button were pressed, and you found yourself with a blank slate for deciding what would be educationally worthwhile to teach, how would you go about deciding?

The essential place to start would be through gaining clarity on exactly what the ‘purpose of education’ is. However, once you start researching such a thing, you rapidly realise that there is wide disagreement about exactly what the starting point might be (Parsons, 2015). According to Dewey (Dewey, 1934), ‘Any education is, in its forms and methods, an outgrowth of the needs of the society in which it exists.’ In tolerant modern democracies, our cultures are so multifarious that it can be difficult to gain clarity or consensus on what we want our school system to focus on.

With the founding of the National Curriculum for England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1988, the goal of education was defined as the delivery of a ‘balanced and broadly based’ curriculum that would develop multiple dimensions of pupils, whilst preparing them for ‘the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of adult life’ (Education Reform Act, 1988). Another such approach is taken by Biesta (Biesta, 2015), who identified a formulation of Qualification (all the ‘stuff’ that young people need to know and be able to do), Socialisation (becoming fit for societal order) and Subjectification (developing as a unique individual). Both of these approaches certainly feel like they contain a nutritious mix in their dimensions. The problem, it would seem to me, is that such formulations – whilst aiming for completeness – neither appear to exhaust all possibilities, nor gel together in a priority-giving harmonious structure.

The difficulty is that any ultimate purpose to education has to closely align with an overall purpose to life. To provide a structure for navigating our way through many of the big debates in education and day-to-day classroom decision-making, I believe that it is necessary articulate a simple, overarching life-goal, which maps onto a single overarching purpose in education.

Lifespace: A harmonising framework for educational purpose and aims

The purpose of life is to obtain meaningful experience. By ‘meaningful’ experience, I will simply suggest something that, the following day, you’re still glad you had (longer timescales could be argued). I would conjecture that such a purpose to life is compatible with all major cultures and life situations – whether seeking to delay ultimate gratification for an afterlife, or seeing very little meaning beyond living in the here and now.

From this life purpose, we can derive that the purpose of education is to increase a person’s capacity for meaningful experience. This all sounds pleasingly simple, but unless this can be operationalised, it is in itself rather meaningless.

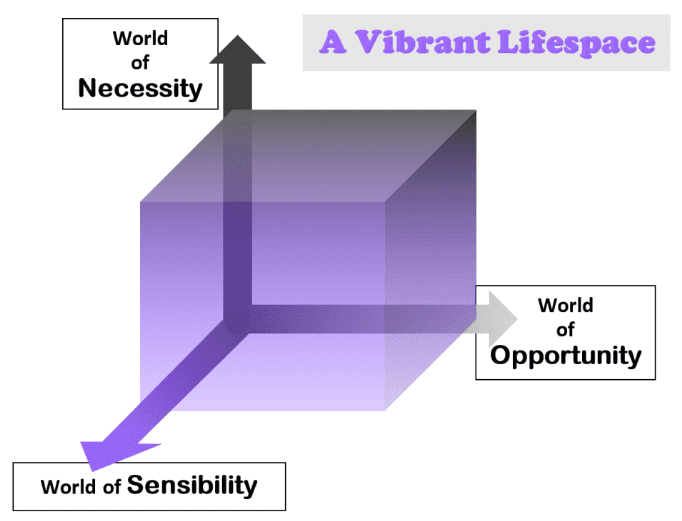

Consequently, over years of reflection, I have developed the following original framework, based on three connecting dimensions that together map out a 3D ‘lifespace’ – a shorthand for describing the scope of our capacity for meaningful experience. The aim in education would be to create the greatest volume of subjectively valuable experience by the expansion of children’s capacities in these dimensions (reduced for shorthand purposes to the acronym SNO) (see Figure 1):

- Our capability to fully attune to the World of Sensibility

- Our ability to fully engage with the World of Necessity

- Our readiness to fully embrace the World of Opportunity.

The World of Sensibility indicates the intrinsic subjective value obtainable from life situations and our actions within them. It is this that gives body to ‘meaningful experience’, and it is something that we can all expand our capacity for, through widening and deepening our exposure to (and awareness of) diverse experiences. Examples could include experiencing success through the act of ‘giving our all’ or crafting something original with our own hands.

The World of Necessity is the requirement of non-negotiable reality, and our ability to be resilient and competent in the face of it, but it is also the route that we so often have to take in order to unlock new levels of opportunity. For example, spending years practising playing an instrument will help you to make the most of opportunities that arise for you to perform to acclaim in front of an audience.

The World of Opportunity is the role of agency and choice in responding to the passage of moments that each new day brings. It is the domain of risk-taking, creative thinking and persistence.

Practical applications

The lifespace concept, with its SNO dimensions, can be used at multiple levels. Priorities within programmes of study and schemes of work can be worked through. Arguments about ‘opportunity cost’ when students are doing ‘fun’ investigations that seem rather time-consuming, considering the limited amounts of knowledge they accumulate by the end of it, can be rationalised in terms of opening up their levels of sensibility, as well as developing their agency to better embrace opportunities. Of course, too much emphasis on this type of activity can impoverish the development of essential knowledge and granular skills.

At the level of day-to-day class teaching, however, this framework can create a hugely flexible way to think around the most pressing needs of individual students:

- What do you really need to be developing at this time?

- What would it be opportunistic for you to be offered in this moment?

- What direct experiences are you lacking that would open up your motivation and sensibility in this area?

School leaders and classroom teachers alike can also use the framework to make sense of the burgeoning plethora of worthy concepts and initiatives that schools find themselves needing to adopt and add to the range of things that they are already doing.

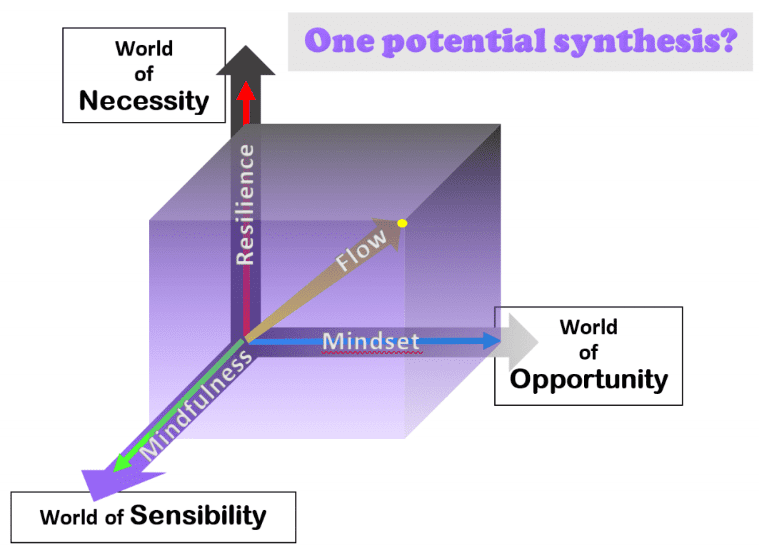

Take, for example, the concepts of resilience (Esquivel et al., 2011), growth mindset (Dweck, 2008) and mindfulness (The Mindfulness Initiative, 2017). Each of the first three maps onto one of the SNO dimensions (see Figure 2). Resilience very much addresses the necessity aspect of life: getting through what you need to get through. Growth mindsetThe theory, popularised by Carol Dweck, that students’ bel... More – that belief that through practice you can keep getting better – is all about maximising our potential in the World of Opportunity. Mindfulness – the focusing of our awareness – is fundamentally about gaining control and heightening sensitivity in the World of Sensibility.

In my own school we are just starting out on the journey of trying to use this framework to increase the confidence, focus and balance of what we do. Through ongoing conversations and an anonymous survey, it became clear that teachers loved the range of things that we do, but occasionally felt weighed down by a sense of apparent conflict between competing aspects. We now have a much bolder, revamped curriculum policy, along with fresh planning tools to help keep a sense of balance and harmony – both at the curricular and lesson-conduct level. Initial informal feedback has been encouraging, but my intention is to re-administer the survey after a year to more carefully gain a sense of impact on teacher experience, before looking at ways in which we can iterate things further such that students and parents too are able to clearly ‘taste the difference’.