Teaching students to Thrive: A case study from an independent London secondary school for girls

PAUL DAVIES, RICHARD TILLETT, SUSANNAH ABBOTT, KATIE SHAPIRO AND REBECCA STEWART, QUEEN’S COLLEGE, LONDON, UK

Introduction

The necessity for students to be educated in resilience is not new (Masten et al., 1990) but it is needed now more than ever. Young people live in a complex world, with daily pressures including the need to perform well academically, the ever-present social media, ‘fear of missing out’ and increased diagnosis of mental health issues and suicide risk. Alongside this is a demand to understand how news is presented and spread, and the wider issues of ecoanxiety (Pihkala, 2020) and living in a future world that is, at times, hard to envisage. It is within this context that our school, an independent school for girls in central London, made the decision three years ago to design a curriculum offer that teaches knowledge and skills around resilience, living in a complex world and how to prepare for future lives.

In addressing this, we took a teacher-led design approach to develop the Thrive curriculum. Bringing together a range of teachers across subject disciplines, and with careful attention to the aims of the school, available pastoral systems and support and the PSHE (personal, social, health and economic education) curriculum, Thrive is now in its second year and has rolled out to both Years 7 and 8. This case study explores how the Thrive curriculum was designed and its impact on students and teachers. We also offer advice for other schools wishing to address curriculum reform of this type and the place of teacher-led approaches in curriculum design.

Approach

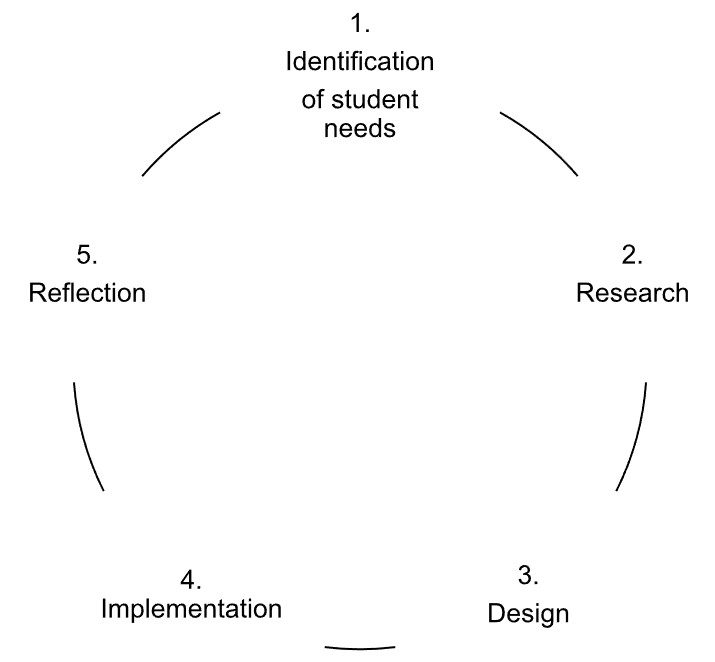

The use of ‘professional communities’ has been shown to provide a positive approach to curriculum reform and has positive impacts on student learning (Handelzalts, 2019). Such an approach also has beneficial impacts on teacher professional learning, especially during the design and pilot stage of curriculum reform (McLaughlin and Talbert, 2006). The teachers involved in the design of the Thrive curriculum represented specialisms in history, politics, art and PSHE, coming from both senior leadership and directorship roles within the school. The team took a teacher-led design approach by following a series of stages, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Stages involved in the design of the Thrive curriculum

In Stage 1, the team met to discuss how they felt the current curriculum was meeting student need, but also areas that were not being addressed. They also drew on personal experiences of being students themselves and having taught for some time in the school. An important part of this reflection was a critical analysis of the ‘themed weeks’ that the school regularly organises, especially ‘Failure Week’, a week of in-class activities focused on how academic failures offer opportunities for learning. It also involved student voice, with students able to share their ideas about how the curriculum could be improved to meet their needs. This took place in various forums, including online questionnaires and discussion during tutor periods and School Parliament. Content analysis was used to analyse this data and identify important themes around students’ views about the content and organisation of the curriculum and preferred approaches to teaching.

Stage 2 was researched-focused, involving engagement with literature, both academic and professional, to better understand student need and how this is theoretically and practically conceptualised. It was during this stage that the key idea of ‘resilience’ became a central aspect of Thrive. Resilience is described by Johnson (2008) as both a process and an outcome. It describes how people are better prepared to cope with and respond to risk and threats to wellbeing and involves an interaction between both personal coping mechanisms and external support (Kaplan, 2005). Alongside resilience, the team drew on the work of Reiss and White (2013), recognising that the notion of a ‘flourishing life’ resonated well with their ideals about how best to prepare students for life in and after school. They also felt that an important skill required by students to embed their learning was metacognition, something that also has wide-ranging positive effects across the whole curriculum (Perry et al., 2019). For this reason, skills associated with reflective learning, sharing learning strategies and encouragement of students to talk about their learning journey were made central to the pedagogy of the curriculum (Quigley et al., 2018). The culmination of Stages 1 and 2 was the development of themes around skills and knowledge that a student needs to be able to ‘thrive’ (see Table 1).

| Year studied | Theme | Example activities |

| 7 | Resilience | Rewording ‘mindset’ sentences; debating attributes of resilient women |

| Kindness | Writing and reflecting upon a ‘gratitude’ letter; reflecting on the novel The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse (Mackesy, 2019) | |

| Truth | Analysis of promotional material associated with Brexit; discussion surrounding the media’s portrayal of women | |

| 8 | Diversity | Analysis of case studies where diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, is not protected; discussing examples where people have taken action to combat inequality |

| Life skills | First aid; finance literacy; cookery skills | |

| Politics and campaigning | Imagining the consequences of a lawless world; campaign for change on an issue of personal importance |

Table 1: Overview of the Thrive curriculum themes

During Stage 3, the team took responsibility for producing resources to support each theme. These included presentations, workbooks and practical activities (see Table 1 for examples). As identified from the student voice data, a key aspect of the design was that group work and individual reflection were central to the learning approaches taken. We are currently in Stages 4 and 5 of the curriculum cycle, with our current Year 8 students coming towards the end of their second year of Thrive lessons. During the past 18 months, the team have shared reflections (see Table 2) about their teaching and student learning and used this to inform redesigning of lesson content and sequence. This process has also involved using student voice approaches, which led to the themes included in the second year of the curriculum, and surveying parents, to better understand the impact that the curriculum is having on students and their families.

Outcomes

The purpose of Thrive is to help students to build resilience and give them knowledge and skills that would help them to succeed inside and outside of school and in their adult life. Students have been generally very positive about Thrive. Some of this can be explained by the low-stakes associated with the curriculum, since it does not have tests or end-of-year examinations. However, students have also commented that the content of the lessons and the nature of the learning approaches adopted are both enjoyable and beneficial. The end-of-year survey carried out in the summer of 2021 revealed that 75 per cent of students felt that the Thrive lessons helped them to ‘grow as a person’. This has been very encouraging, since the curriculum was designed to support this aspect of personal development. Likewise, 70 per cent of students felt that the Thrive lessons were beneficial to their wellbeing. The school has made some major changes to its curriculum offer with regard to wellbeing, with students having access to school counsellors, the PSHE programme having wellbeing as a major focus and the pastoral support concentrating on this aspect of the student experience.

One concern of the curriculum reform team was that some students might perceive the lessons as unimportant compared to the ‘normal’ curriculum. The quality of work produced by students – for example, their effort and resolve demonstrated in the politics and campaigning module, where students lobby politicians for change on issues of personal importance – shows exactly the opposite, with students approaching the task in a mature and serious way. Likewise, our survey revealed that this was not the case, with 77 per cent of students identifying Thrive as being at least as important as other subjects, while also offering something else, as these student comments demonstrate:

Thrive lessons matter because our teacher has taught us to be better versions of ourselves.

Thrive has helped us through situations that we are not proud of.

A key aspect of Thrive is to promote ‘deep thinking’ to help students see that, while not the same as traditional subjects, the concepts discussed in lessons are complex and require hard work and effort from individuals and the class as a whole. A good example of a student response to this aspect of Thrive comes in this quote from the survey:

Amazing lessons: current and relevant, thought-provoking.

Parental perception of Thrive has also been very positive. Both anecdotal and survey results show them to be impressed that the school has developed this curriculum approach. From the survey, 80 per cent of parents said that Thrive had improved their child’s mental health. Parent comments from the survey reveal that they are seeing positive change in their children. For example:

It’s really good that the school puts the extra effort in this subject and focuses on mental wellbeing, which is so important for the girls at this age. Please keep going with the Thrive lessons.

The teachers involved in Thrive have also reported significant impacts on their professional development. As Table 2 shows, being involved in the design of the curriculum brought with it challenges but also many rewards, which have important implications for teacher change and identity (McLaughlin and Talbert, 2006). Teaching Thrive is inevitably more challenging than traditional subjects, but also liberating, allowing staff to build different relationships with students and for students to see them in a new light.

| Reflections on designing Thrive | Reflections on teaching Thrive |

| The whole concept of teaching Thrive on the curriculum was an exciting one to put together. We started from first principles: what do we think our students need, beyond subject-specific content and the PSHE schemes of work? It was good to be able to tailor the topics towards our own situation.

It is great to collaborate with other senior leaders on this project and to be able to work with students on what we cover, rather than being dictated to by exam boards or the content of textbooks. This was a totally new experience for me. Not having to adhere to the constraints of an exam-based subject was exciting and felt wonderfully ‘radical’. When the possibility of opening up the curriculum was floated, I created a matrix of the things I believed young people needed for growth, wellbeing and holistic development, based on my own research and personal experience of being at a school. I was very interested in failure because of my own lack of it when I was at school, personal experiences of perfection paralysis and other things that I had felt were lacking but were essential survival skills. It felt exciting to be developing a curriculum that really gives space for the skills and knowledge that I believe are more than ever essential to meet the needs of young people today. |

I find it liberating to teach something of our own design, and which isn’t adequately covered elsewhere. I do think it provides our students with valuable, transferable skills.

At times it was difficult, as lessons I thought would be brilliant did not have the outcome I intended. I have walked out of some Thrive lessons feeling that I am on top of the world. Walking out of those lessons reminded me of my NQT days when I taught my best lesson yet and felt that happy buzz for days to come. Teaching Thrive has been a learning curve because, as an art teacher, I am not used to teaching without an art material in the room. ‘Material’ in Thrive is different, and I am still getting to grips with pitching content at the appropriate level. It is fun to devise an open curriculum that can be creative, flexible and responsive to each group’s needs. I like getting to know the students more, and letting them know a bit more about me as we cover topics of ‘life’. I try to embody and role-model the skills and ideas being explored, because I believe seeing teachers practising what they preach is extremely powerful. It’s a lesson I spend a lot of time reflecting on, but also wishing we had longer to cover everything and put skills into practice. |

Table 2: Teacher reflections on their involvement in the design and teaching of the Thrive curriculum

Conclusion

The Thrive curriculum has effected change in our school community, across students, parents and staff. For students and parents, Thrive is supporting them in a new ways of thinking, not found in traditional curriculum subjects, and equipping them with both thinking and practical skills for engaging with 21st-century life at school and beyond. For staff, the process of working as curriculum designers has demonstrated the power of bringing together multidisciplinary teams, while engaging with educational research literature with a clear purpose has helped the team to build confidence in applying theoretical ideas to practice and reflect on their journeys as teachers.

A study of this type always has limitations. The nature of our student cohort and parents means that it is hard to generalise across other settings; indeed, it is the nature of our specific setting that led to us developing Thrive. However, initiatives like Thrive are something that we would strongly recommend schools engage with and recognise as an important aspect of their curriculum offer. All children must deal with uncertainty, and the changes that we have observed in students are palpable. Giving staff time to lead curriculum reform also has important implications in other settings. For us, breaking down the barriers between subject staff and between staff working in different managerial roles led to the design of an interesting and useful curriculum offer, as well as having an important influence on collegiality and supporting collaboration. This can only be a good thing for whole-school development.

- Handelzalts A (2019) Collaborative Curriculum Development in Teacher Design Teams. In: Pieters J, Vookt J, Roblin NP (2019) Collaborative Curriculum Design for Sustainable Innovation and Teacher Learning. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 159–173.

- Johnson B (2008) Teacher–student relationships which promote resilience at school: A micro-level analysis of students’ views. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 36(4): 385–398.

- Kaplan HB (2005) Understanding the concept of resilience. In: Goldstein S and Brooks RB (eds) Handbook of Resilience in Children. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 39–47.

- Mackesy C (2019) The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse. London: Ebury Press.

- Masten AS, Best KM and Garmezy N (1990) Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology 2(4): 425–444.

- McLaughlin MW and Talbert JE (2006) Building School-Based Teacher Learning Communities: Professional Strategies to Improve Student Achievement. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Perry J, Lundie D and Golder G (2019) Metacognition in schools: What does the literature suggest about the effectiveness of teaching metacognition in schools? Educational Review 71(4): 483–500.

- Pihkala P (2020) Eco-anxiety and environmental education. Sustainability 12(23): 10149.

- Quigley A, Muijs D and Stringer E (2018) Metacognition and self-regulated learning: Guidance report. Education Endowment Foundation. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Metacognition/EEF_Metacognition_and_self-regulated_learning.pdf (accessed 6 July 2023).

- Reiss MJ and White J (2013) An Aims-Based Curriculum: The Significance of Human Flourishing for Schools. London: IOE Press.