By Jo Van Herwegen, Professor of Developmental Psychology and Education, UCL’s Institute of Education

Recent evidence shows that students with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) have lower educational outcomes compared to their peers and that this gap continues to increase (Tuckett et al., 2021). Although previous reviews have addressed how these students can benefit from best practice related to universal teaching, it is unclear what the evidence base looks like for targeted interventions. Most previous studies that have examined the impact of targeted interventions have either focused on specific targeted interventions (e.g. Does Lego Therapy work?) or on specific groups (e.g. Do targeted interventions work for students with dyslexia?). Whilst useful, such overviews do not allow insight for which educational outcomes or groups of SEND we lack research evidence for, or whether particular targeted interventions might benefit various educational outcomes and groups with SEND. In addition, many teachers have difficulties accessing research evidence, and thus might be limited to make research-informed decisions about which targeted interventions to use with their students.

The MetaSENse study carried out by researchers at the Centre for Educational Neuroscience and the Department of Psychology and Human Development at UCL aimed to address these issues. The study was funded by the Nuffield Foundation and included three phases:

- phase 1 included a review of the current research on targeted intervention

- phase 2 focused on interviews with practitioners to examine barriers and best practice to implementation, and

- phase 3 included the co-production of a new toolkit and searchable database to help educators make better informed decisions around targeted interventions.

What do we know about targeted interventions for students with SEND?

The first phase examined the existing research evidence base. It included a systematic review and meta-analysisA quantitative study design used to systematically assess the results of multiple studies in order to draw conclusions about that body of research of studies that used Randomised Controlled Trials and Quasi-Experimental Designs to evaluate the impact of targeted interventions for students with SEND aged four to 25. The systematic review identified 467 studies worldwide reporting on 1,758 outcomes, predominantly related to reading (n = 1139), with fewer studies focusing on writing outcomes (n = 279), mathematical outcomes (n = 284), science outcomes (n = 3), and general attainment (n = 53). Only 21 studies were from the UK.

Overall, the results from the systematic review and meta-analysis are positive in that targeted interventions can raise educational outcomes among students with SEND by an average of five months of progress compared to those receiving teaching-as-usual or active control interventions. So, there is evidence that some interventions can be effective!

Interestingly, the intervention effects did not vary according to whether they were delivered in a small group, or one-to-one, or who implemented them. Of course, the meta-analysis looks for overall effects. This does not mean that all interventions work equally well in small groups rather than on a one-to-one basis, but it does mean that we can explore whether more of these targeted interventions can be delivered in small groups or to a whole classroom. With some adaptation, some of these good practices could apply to a whole group of children and this might benefit 1) children who have not yet been identified or diagnosed with SEND and 2) reduce waiting lists for children who are currently waiting to receive certain interventions on a one-to-one basis.

The review also shows that effects were larger for mathematical outcomes than for reading outcomes. This can be explained by the fact that mathematics is multi-componential (e.g., counting component, an arithmetic component, algebra) and that most targeted interventions focused on a specific component. In contrast, most reading interventions targeted broader reading abilities and thus, it is likely that it takes much longer to achieve similar improvements. This information is helpful in that teachers should consider when they review what works for students with SEND. If they review targeted interventions in their practice after only one term for example, this might not be long enough to see improvements for certain interventions that target broader skills, compared to very specific ones. However, most interventions in the review were implemented for only one term and for both reading and mathematics there was evidence that targeted interventions work. As many students with SEND often have low mathematical outcomes, the findings from the MetaSENse review show that mathematical interventions should be prioritised more, in that they can positively benefit students with SEND.

However, the review also highlights some gaps in the research evidence. This was particularly true for those students with intellectual disabilities, physical disabilities, and sensory disabilities such as vision and hearing impairments, as 50 percent of the studies focused on students with specific learning difficulties. There was also a lack of studies that examined what worked for students with SEND in secondary schools, especially for mathematical abilities. In terms of educational outcomes, there was a lack of focus on general attainment and on science outcomes. This shows that for a number of SEND groups it is difficult to advise teachers about evidence-based intervention approaches. However, in a next stage we hope to examine what the core components are from successful interventions that have been included in the MetaSENse study, as this will allow us to extrapolate what might work for those groups that have been under-researched.

What are the barriers for educational practitioners to implement evidence-based targeted interventions?

In phase 2, we interviewed 33 educational professionals from mainstream and special primary and secondary schools in England as well as various professionals who work for local authorities but work with schools (e.g. educational psychologists, specialist assessors etc). The in-depth individual interviews focused on current targeted intervention practices and how evidence is used in schools, and explored barriers to implementing effective practices.

Interviews revealed that educational practitioners varied in their understanding of evidence-informed practice and how to access this information. Interviews also revealed practitioners experienced barriers in trying to implement interventions, with mainstream schools, especially secondary schools, showing a preference for off-the-shelf interventions. The interviews also highlighted that what is evaluated in the research literature is very different from the targeted interventions used in the classroom.

Whilst most schools collect data on pre-and post-intervention abilities, very few review this data across individual students to see what interventions are working and which ones have stopped working and might need to be reviewed or replaced. So, whilst many schools seem to have a long list of targeted interventions they can implement in their schools, it seems most schools do not have a systematic approach when it comes to evaluating the targeted interventions they are using. Last but perhaps most importantly, many interviewees discussed the need to adapt interventions to their specific setting or students, or that interventions were being watered down due to the fact that training for delivering the targeted interventions often happened through cascaded in-house continuous professional development (CPD) training (i.e. one member of staff would receive the training and then train further staff in house). Yet, often no record was being kept of the implementation of the interventions and how this might differ from the original intervention or how the intervention was evaluated in research studies.

As such, the findings from phase 1 and phase 2 show that whilst we do know that some interventions work, practitioners do not always have access to the research evidence of what works. This limits their ability to make evidence-informed decisions on which interventions to use with particular groups with SEND.

The MetaSENse toolbox: A searchable database to help teachers and professionals make evidence-informed decisions

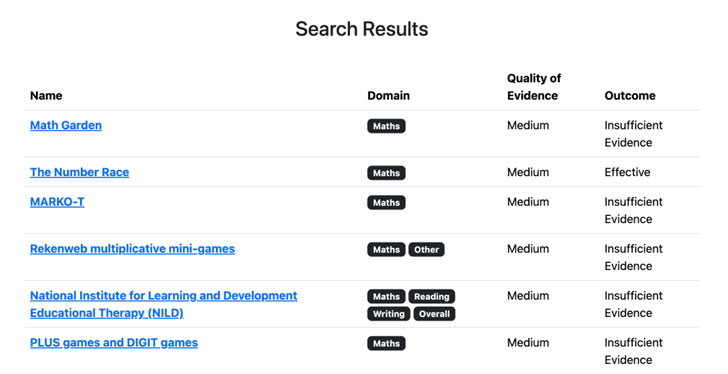

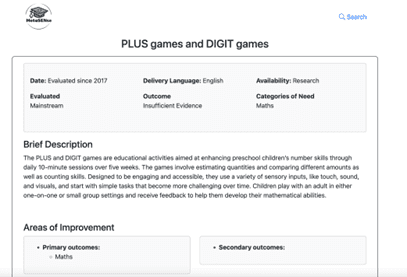

Combing the findings from phase 1 and phase 2, the third and final phase included the co-production of a toolkit, an online tool that allows educators to search for evidenced-based approaches for particular educational outcomes and SEN groups. The toolkit includes a searchable database that includes those targeted interventions that were included in the review and are available, either commercially or via researchers’ webpages, for teachers to use or purchase. Educational professionals also told us that it was important not only to ensure that interventions are included that can be accessed by teachers, but also to include why these interventions might work and to provide a short description of what each study that evaluated the intervention found. As such the database allows teachers to search by either educational outcomes, SEND group, age group, and many other factors. For example, teachers might want to know what interventions are available to improve mathematical outcomes for students with various SEND in Key stage 1. Others might want to know if a particular targeted intervention works and can search using the name of the intervention. The database also allows users to search all interventions that have been evaluated for particular groups of SEND (for example, autism or ADHD). Each search then returns an overview of all the interventions available (see Figure 1a) and by clicking on the name of the intervention a new form opens that describes that intervention, what is required to implement it, how the intervention works (theory of change), and the research outcomes (See Figure 1b).

Figure 1a – image of the search function

Figure 1b – an example of the intervention overview

The toolkit will be updated in the years to come to ensure it remains up-to-date. At the moment, the database only includes studies that have measured educational outcomes, and thus very few interventions relate to behavioural improvements or wellbeing. Also, as there is already a very helpful database for speech-and language approaches we did not include these interventions in the MetaSENse database. However, we hope to expand on the MetaSENse database in the near future to include non-academic outcomes as well.

“I think this could have a huge impact on interventions in school. I know teachers often do not have the time to search for new interventions and find the evidence of if it works. I believe having one place to go and easily find new things to try will greatly improve what schools are able to offer and hopefully improve the quality.” (Headteacher, anonymous)

Moving forward: How do we ensure better outcomes for students with SEND?

Although students with SEND have lower educational outcomes, the MetaSENse review shows that there is a growing evidence base of targeted interventions that can improve these students’ outcomes. However, teachers have problems accessing research studies and do not always review what works in their classroom. In moving forward, we hope that teachers will systematically review the interventions that they are using in their classroom to improve reading, writing, and mathematical abilities and that they will use the MetaSENse database to make evidence-based decisions to select the best approaches.

In addition, we would encourage headteachers and SENDco’s to systematically capture the data they collect to evaluate the impact of interventions in their schools. They may also want to explore how they can capture data from a control condition. For example, can the school first assess the child with SEND a few weeks apart before the child starts the intervention to capture a baseline or can another school, that has similar students in their school but who are not using a specific intervention, provide control data? This might require the schools to work together and decide how best to capture pre-and post- data. However, if schools can work together with universities or research centres, these might be able to provide some reliable assessment measures and even help with the data analyses. I know our colleagues at the Centre for Educational Neuroscience would be very happy to help with this! By educational professionals and researchers working more closely together, it will be possible to close the research-practice gap in relation to SEND.

Finally, we would encourage schools to invest in CPD for teachers and teaching assistants (TAs). Firstly, by providing them with more insight into developmental psychology and specific knowledge about the different groups of SEND they work with. We have developed some affordable self-paced online short courses that can help with this. Secondly, to include CPD regarding what research evidence is, where to find it, and how to assess evidence as well as how to evaluate their own practice. Research has shown that journal clubs can support educational practitioners’ research-informed practice (Breckon & Dodson, 2016).

For more information about the MetaSENse study and the full study report please visit the website: http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/metasense/

The MetaSENse study was carried out by researchers at UCL’s Institute of Education: Professor Jo Van Herwegen, Thomas Masterman, Dr Catherine Antalek, Professor Chloë Marshall, Professor Julie Dockrell, and Dr Rebecca Gordon; and Professor Michael Thomas from the Centre for Educational Neuroscience, Birkbeck, University of London.

References

Breckon, J., & Dodson, J. (2016). Using evidence: What works? A discussion paper. Alliance for useful evidence. Available at: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/using_evidence_what_works.pdf accessed on 5th November 2024

Galuschka, K. et al., (2020). Effectiveness of spelling interventions for learners with dyslexia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Educational Psychologist, 55(1), 1-20, DOI: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1659794

Narzisi, A. et al. (2021). Could You Give Me the Blue Brick? LEGO®-Based Therapy as a Social Development Program for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 11, 702. https://doi.org/10.3390/ brainsci11060702

Tuckett, S., Robinson, D., & Bunting, F. (2021). Measuring the Disadvantage Gap in 16-19 Education. Education Policy Institute. https://epi.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2021/02/Measuring-the-16-19-disadvantage-attainment-gap_EPI-2021.pdf.