Leadership for creative thinking in schools: How current research and innovation is putting creativity back into schools in England

BILL LUCAS, PROFESSOR OF LEARNING, UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER, UK

The curricula of both Scotland (Creative Scotland, nd) and Wales (Welsh Government, 2015) actively encourage creative thinking. In England, however, creative thinking is largely absent in the current National Curriculum. Recently, through the Creativity Collaboratives initiated by Arts Council England (Durham University, 2019), and arising from an intervention to evidence creativity in Australia (Lucas, 2021b), there has been greater emphasis on creative thinking in England. A pilot study by Rethinking Assessment and ACER UK is currently exploring ways in which teachers can evidence the development of creative thinking in pupils within the current English National Curriculum. This renewed interest is increasingly focusing on leadership (Lucas et al., 2021) and on the need to develop appropriate strategies for embedding creative thinking in schools.

Lessons for creative leadership

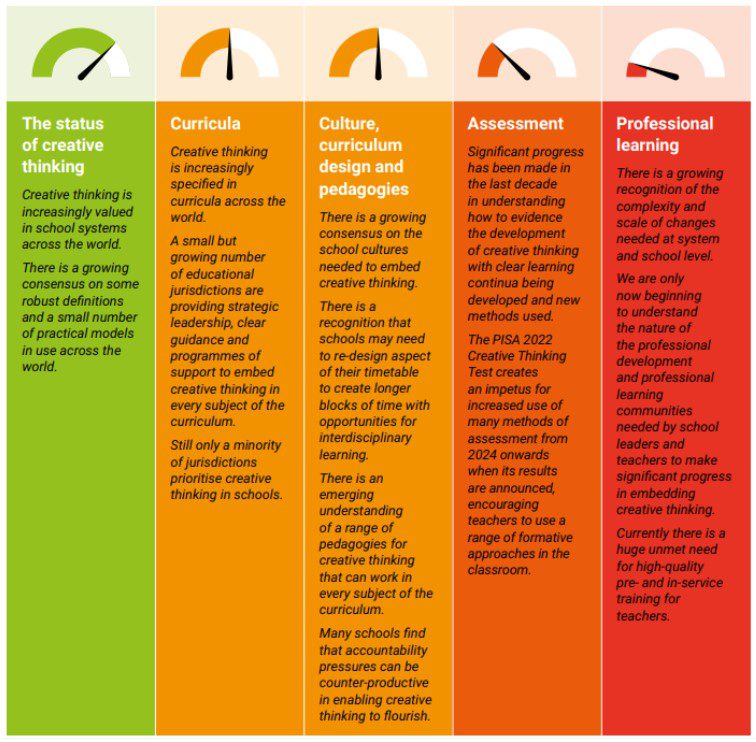

In a recent study for the Global Institute of Creative Thinking (Lucas, 2022) it was clear that, across the world, much progress is being made. Coloured dashboard indicators give a snapshot of this graphically (Figure 1). They also reveal that, while the status of creative thinking, its place in the curriculum and our understanding of curriculum design and creative pedagogies is growing, it is not yet clear how best creative thinking can be assessed. For system change in England to be achieved, there will need to be a considerably enhanced understanding of the kinds of professional learning that are effective for school and system leaders.

Figure 1: Creative thinking in schools across the world – a snapshot of progress (Lucas, 2022)

Research by Stoll and Temperley (2009) identified nine conditions needed for creative leaders promoting and nurturing creativity in others. They need to:

- Model creativity and risk-taking

- Stimulate a sense of urgency to overcome inertia

- Expose colleagues to new thinking and experiences

- Self-consciously relinquish control creating an ethos favourable to risk-taking

- Provide time and space and facilitate the practicalities

- Promote individual and collaborative creative thinking and design

- Set high expectations about the degree of creativity, pushing people to be imaginative and to think originally

- Use failure as a learning opportunity

- Keep referring back to core values.

Taken together, these pointers form the agenda for the creation of a professional learning curriculum for school leaders.

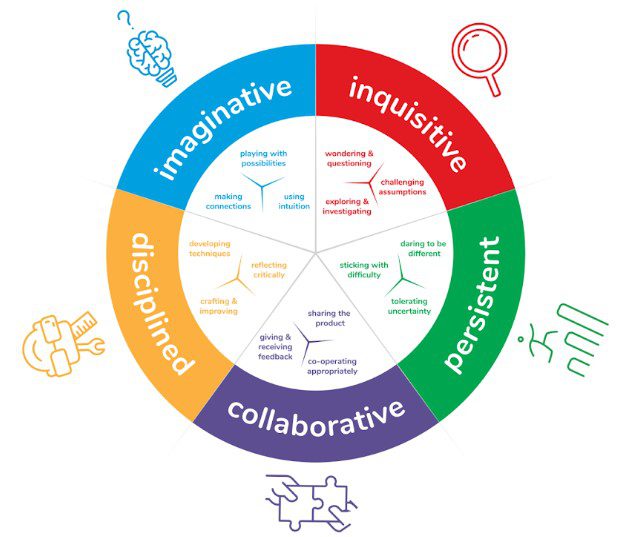

Recently, with Louise Stoll and colleagues from the University of Winchester and from Creativity, Culture and Education (CCE; www.creativitycultureeducation.org), we have drawn on research and promising practices from across the world to develop Creative Thinking in Schools: A Leadership Playbook (Lucas et al., in press). Given that creativity and creative thinking are largely invisible in the curriculum of schools in England, a critical first step is the development of a real understanding of creative thinking among school staff, as the Durham Commission (Durham University, 2019) showed. The Centre for Real-World Learning (CRL) framework, now in use in more than 30 countries across the world, lifts the lid on the abstract concept of creativity, showing how creativity can be conceptualised as five creative learning habits, each of which can be broken down into three sub-habits (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CRL’s creative thinking framework, developed with CCE for schools in the north-east of England

A second key finding from our research is the reminder that school leaders wishing to embed creative thinking in their schools need to think not just about their pupils’ creativity but also about their staff’s. For some colleagues, this is a welcome revelation; for others less confident in their creative self-efficacy, it can require support.

The third conclusion we have drawn is that making schools creative places challenges school leaders and staff to rethink the purpose of school. If the goal of education is to grow young people who are deeply knowledgeable and skilled and who are routinely able to exercise their imagination, inquisitiveness, persistence, collaboration skills and discipline as learners, then, in the current system in England, this requires a degree of boldness.

The evidence we have gathered suggests that school leaders seeking to embed creative thinking in their schools need to have an explicit theory of change, recognise the importance of distributed leadership, cultivate a culture of creative innovation and risk-taking, and rethink their schools’ structures, systems and external partnerships. They will need a razor-sharp focus on curriculum design, pedagogy and assessment, all the while building a professional learning community of staff within and beyond school. The icons next to each of the five creative habits in Figure 2 are just one example of the way in which school leaders can consistently reinforce creative concepts across all aspects of a school’s life.

Above all, we are constantly reminded that the active support of headteachers is critically important in order for any significant change to happen in schools.

Learning from the Creativity Collaboratives

In 2021, eight Creativity Collaboratives, clusters of eight to 12 schools spread across the regions of England, were awarded significant funding by Arts Council England. The three-year programme is exploring how varied approaches to teaching for creativity, with a particular focus on inquisitiveness, support all pupils and contribute to school improvement in a diverse range of settings. It aims to build networks of schools to test innovative practices in teaching for creativity, sharing learning to facilitate system-wide change.

Already some key lessons are emerging. The first of these has already been touched on: the need for actively engaging a wide range of school and system leaders in the process. Other learning includes:

- There is a need to free up time for at least one member of staff to act as a creativity champion across the cluster of schools, proactively coordinating professional learning and the interchange of ideas.

- It is important to track impact against a theory of change from the outset to better understand how enhanced creative thinking is affecting staff and pupils (and also to provide OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services with data on how intent, implementation and impact are working in practice)

- There is great benefit in ‘split-screen’ or integrated curriculum planning – an explicit cross-mapping of what appears in the programme of study for a specific subject against the aspects of creative thinking being embedded. The metaphor of the screen suggests that, in devising curriculum content, teachers have an equal eye on the discipline and on the sub-habits of the creativity being taught. So this might involve developing the ability to challenge assumptions in a scientific investigation. A sub-habit such as crafting and improving work or giving and receiving feedback could easily map onto any subject, whereas one such as making connections might map well onto the use of metaphor or simile in English, for example.

- Signature pedagogies harness those teaching and learning methods that are most likely to produce the desired creative outcomes. These include techniques such as mantle of the expert, philosophy for children, problem-based learning and many other well-evidenced approaches(Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019; Lucas and Spencer, 2017).

Culturally, perhaps the biggest hurdle still to overcome is the long-standing association between creativity and the arts. Here the challenge is to exemplify how creative innovation is equally at home in every discipline of the curriculum and in all aspects of life; it is ubiquitous.

Rethinking assessment (and curriculum and pedagogy)

Partly because of the examination debacles during the pandemic, and partly because of the emergence of new approaches to assessment in schools, the importance of assessing creative thinking has grown. The PISAThe Programme for International Student Assessment, a worldw Creative Thinking Test 2022 (OECD, 2022) offers a proof of concept that it can be done – that an online one-hour scenario-based test of creativity can reliably evidence creative thinking. In the state of Victoria in Australia, pupils’ critical and creative thinking has been assessed for nearly a decade using similar but more extended approaches (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, nd). Central to the Victorian model is the underpinning of clear scope and sequence documents, describing what progression looks like for pupils across the school system (Victorian Curriculum, nd).

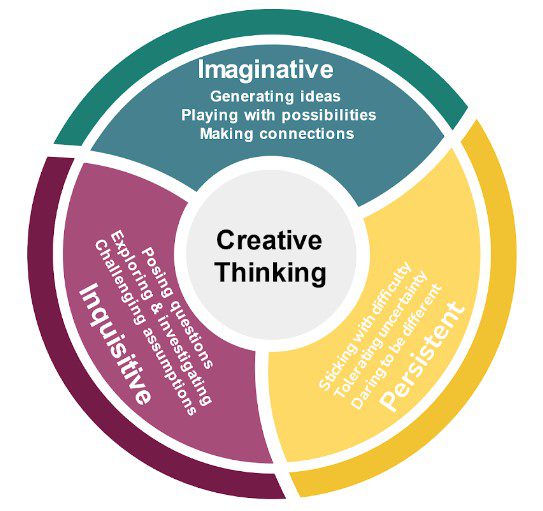

In 2022, Rethinking Assessment and ACER UK embarked on a professional learning intervention to explore ways in which teachers could learn how to assess pupils’ creativity. The study takes a version of the widely used CRL model of creative thinking, along with work undertaken by ACER in Australia (Ramalingam et al., 2020) as its starting point (Figure 3). It requires four to six teachers working collaboratively in some 20 schools to split-screen plan a term’s curriculum across one or more of five subjects: English, science, history, art and design, and design and technology. Teachers then select appropriate signature pedagogies and use three assessment methods in which they have been trained: pupil self-reported questionnaires, their own judgment of progress against a learning progression, and the moderation of a portfolio of pupils’ work, again using the learning progression.

Figure 3: Rethinking Assessment and ACER UK’s draft model of creative thinking

Pupil questionnaires take the three creative habits and their three sub-habits as the starting point for a simple nine-item, age-appropriate questionnaire for pupils, which is used before, during and at the end of the intervention.

It is too early to say whether this innovation in curriculum design, pedagogy and assessment will fit easily and reliably enough into busy teachers’ lives, but early indications are that it does.

Being able to evidence progression in creative thinking is one piece of a larger jigsaw in terms of system innovation. The ultimate goal is for all young people to emerge from formal education with a digital learner profile – a much fuller description of what they know, what they can do, which learning habits they have securely developed and which learning experiences they have had, than can be provided by public examinations alone. Rethinking Assessment’s prototype profile is just one of a number being piloted across the world (Rethinking Assessment, 2022).

The kind of assessment innovation just described will feed into the 3Cs of success depicted in the profile – creative thinking, communication and collaboration – complementing the ‘Building Blocks’, or core literacies and numeracies, long referred to as the 3Rs (Rethinking Assessment, 2022). It is our hope that, as they were in the first decade of this century, schools in England will be known across the world for their rigorous, values-driven innovation in the area of creativity and creative thinking.

- Creative Scotland (nd) Scotland’s creative learning plan. Available at: www.creativescotland.com/resources/our-publications/plans-and-strategy-documents/scotlands-creative-learning-plan (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Durham University (2019) Durham Commission on Creativity and Education. Available at: www.dur.ac.uk/resources/creativitycommission/DurhamReport.pdf (accessed 21 December 2022).

- Lucas B (2021) A field guide to assessing creative thinking in schools. FORM. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/19WiqUOHWgODLSxDID4RnMMD0-25dJa5F/view (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Lucas B (2022) Creative thinking in schools across the world: A snapshot of progress in 2022. Global Institute of Creative Thinking. Available at: https://uploads.strikinglycdn.com/files/f5005576-eb0e-4d24-b4a1-823147c95c34/GIoCT-Creative-thinking-report_Final%2017%20October%202022.pdf?id=3948255 (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Lucas B et al. (in press) Creative Thinking in Schools: A Leadership Playbook. Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

- Lucas B and Spencer E (2017) Teaching Creative Thinking: Developing Learners Who Generate Ideas and Can Think Critically. Carmarthen: Crown House Publishing.

- Lucas B, Spencer E and Stoll L (2021) Creative leadership to develop creativity and creative thinking in English schools: A review of the evidence. The Mercers’ Company. Available at: www.creativityexchange.org.uk/asset/223 (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2022) Thinking outside the box: The PISA 2022 Creative Thinking Assessment. Available at: www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/creative-thinking (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Ramalingam D, Anderson P, Duckworth D et al. (2020) Creative thinking: Skill development framework. Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). Available at: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1041&context=ar_misc (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Stoll L and Temperley J (2009) Creative leadership: A challenge of our times. School Leadership & Management 29(1): 65–78.

- Victorian Curriculum (nd) Critical and creative thinking: Scope and sequence. Available at: https://victoriancurriculum.vcaa.vic.edu.au/critical-and-creative-thinking/introduction/scope-and-sequence (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (nd) Assessment resources. Available at: www.vcaa.vic.edu.au/curriculum/foundation-10/resources/criticalandcreativethinking/assessmentresources/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 23 March 2023).

- Vincent-Lancrin S, González-Sancho C, Bouckaert M et al. (2019) Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Welsh Government (2015) Creative learning through the arts – an action plan for Wales: 2015–2020. Available at: www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-02/creative-learning-through-the-arts-an-action-plan-for-wales-2015-2020.pdf (accessed 23 March 2023).