The role of the humanities in a balanced and broadly based primary curriculum

There is increasing concern within and beyond the teaching profession at how the primary curriculum in England in recent years has become unbalanced, with the emphasis on decontextualised literacy and numeracy skills and measurable outcomes. This was a major concern of the Cambridge Primary Review (Alexander, 2010), which critiqued and provided direction for practice in England’s primary school curriculum. Its analysis remains highly relevant today. In particular, it highlighted that Curriculum 1 – ‘the basics’, now usually associated with those aspects of English and mathematics most easily tested – has consistently dominated the primary curriculum at the expense of Curriculum 2 – ‘the rest’, including the humanities and the arts.

The primary curriculum continues frequently to be narrow and unmotivating for many children, with the humanities given so little time that teaching is sometimes superficial and focused on children acquiring factual knowledge. This critique is reflected in the draft of Ofsted’s revised inspection framework, calling for a greater emphasis on a broad, rich curriculum in Key Stage 2 (OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – a non-ministerial department responsible for inspecting and regulating services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills, 2019, para 161) though, disappointingly, it is deemed appropriate for teachers in Key Stage 1 to focus more narrowly on reading, writing and mathematics.

The humanities, as understood in primary schools, are usually seen as history, geography and, sometimes, religious education and citizenship, though as taught, these subjects often lead or contribute to broader-based cross-curricular themes and projects.

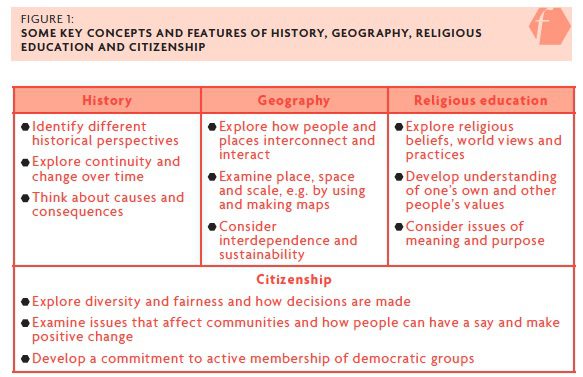

A more fruitful perspective for primary schools may be to consider what the humanities are intended to achieve — the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of the humanities as ‘learning or literature concerned with human culture’ provides a good starting point (Eaude, 2017). This leads one to see the humanities as those areas of study that help children to explore what it is to be human and how people live, think and interact in diverse societies, cultures and environments, especially in terms of time, place and belief. Such areas of study include literature, philosophy, learning a foreign language and drama, as well as history, geography and religious education. These subjects have distinctive and valuable concepts, knowledge and ways of working, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Nussbaum (2010) argues that the humanities are essential as a foundation for democratic citizenship, which requires children (and adults) to engage with complex ideas in thoughtful and reflective ways, taking account of other people’s views and being prepared to listen, discuss and learn to disagree respectfully. Such an approach enables children to become more empathetic and can help to challenge limited, partial and biased views since ‘it is easier to treat people as objects to be manipulated if you have never learned any other way to see them’ (Nussbaum, 2010, p. 23).

Reflecting on the role of the humanities in ‘troubled times’, Eaude et al. (2017, p. 5) concluded that ‘there is a pressing need for humanities education in an increasingly complex world; and to argue the case for humanities on the grounds of the development of the “whole child”. In particular we would advocate for children:

- understanding concepts related to human culture such as time, space and belief in how human beings can understand themselves and their relationship with the natural world, places and with each other;

- developing skills and habits associated with critical thinking such as assessing and interpreting information

- exploring their own identities, values and beliefs and enabling them to be interested in those of other peoples

- learning to understand, and empathise with people who are different, as well as those who are similar, challenging stereotypes and becoming more humane and compassionate individuals.’

The humanities matter because they enable children to:

- consider questions about the meaning and purpose of their lives

- explore their own identities, values and beliefs and concepts such as time, space and faith

- develop skills and habits associated with critical and creative thinking

- extend their cultural and imaginative horizons

- learn to empathise with people who are different, as well as those who are similar, thereby celebrating diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences, exploring common ground and challenging bias and prejudice

- learn about democracy, global citizenship and sustainability

- strengthen a sense of care for themselves, each other and the planet, in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015).

The ways of working associated with the humanities, such as fieldwork, enquiry, observation and interpretation, encourage critical thinking that involves ‘the kinds of habits of mind, commitments or sensitivities [that] include such things as open-mindedness, fair-mindedness, the desire for truth and an inquiring attitude’ (Bailin et al., 1999, p. 281). Such qualities are essential in a world where information can be accessed easily, but where children, and adults, cannot be sure who and which information to trust.

The humanities are the basis of how children learn to become responsible citizens, as they are encouraged to engage with complex and debatable ideas. They make a vital contribution to children’s spiritual, moral, social and cultural (SMSC) development, an area that, though legally required, is often misunderstood and given insufficient attention. Moreover, the humanities provide an excellent context for learning and applying the skills associated with literacy and numeracy. For instance, children in Key Stage 1 are likely to find studying their local community or their and their classmates’ families an interesting and meaningful context for reading and writing, along with hearing stories, drawing buildings and portraits, and making maps – and much else besides. In Key Stage 2, the humanities enable children to investigate and compare their own and other cultures and explore the challenges facing the world in which they are growing up, such as reasons for and the effects of conflict, climate change and differences of beliefs, while using and embedding a wide range of skills.

There is no single way to organise the curriculum that will lead to these outcomes. They can be achieved through discrete subject lessons, though teachers must be prepared to cross subject boundaries and encourage children to do so. The humanities can also be taught well through cross-curricular themes, though teachers must be aware of, and help children to understand, the key concepts and knowledge of different subjects, as highlighted in Figure 1. Activities such as hearing stories and engaging with drama – whether as an audience member or participant – are well-tried ways of enabling children to learn about other people and themselves, and can be used successfully across the humanities.

Teaching the humanities well is not easy, particularly when dealing with abstract and sometimes controversial ideas, such as racism, migration or damage to the environment. Teachers require good subject knowledge, but more important is pedagogical content knowledge in order to select and structure subject knowledge so that lessons are engaging and meaningful for that particular group of children (Eaude, 2018). Teachers need to be enthusiastic, responsive to new ideas and not too worried if lessons do not turn out quite how they had planned – essentially, they need to be risk-takers (Catling, 2017). Sometimes, primary teachers are concerned about their lack of subject knowledge as a result of the limited time given to the humanities in initial teacher education and few opportunities for career-long professional learning. However, the ways of working described above can be gradually introduced and the relationships and expectations associated with these built up over time, so that more difficult and controversial issues can be addressed in thoughtful and respectful ways.

There is a real and pressing need to promote the humanities as an essential dimension of the primary curriculum – see Figure 2 (Eaude et al., 2017; Ogier and Eaude, forthcoming).

A significant new way of doing so is the Humanities 20:20 campaign (www.humanities2020.org.uk), to be launched in May 2019, which aims to:

- raise the profile of the humanities in primary schools, especially in history, geography, religious education and citizenship

- empower all those involved in schools to consider how they can use the humanities as a context for educating children for the complex but fascinating world in which they live

- provide ways of sharing and encouraging creative, imaginative approaches.

You can follow Humanities2020 on Twitter to find out more. We hope that, working together, primary headteachers and teachers can restore the humanities to their rightful place in the education of the whole child.

References

Alexander R (ed) (2010) Children, their World, their Education – Final Report and Recommendations of the Cambridge Primary Review. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bailin SR, Case R, Coombs JR et al. (1999) Common misconceptions of critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies 31(3): 269–283.

Catling S (2017) High quality in primary humanities: Insights from the UK’s school inspectorates. Education 3–13 45(3): 354–365.

Eaude T (2017) Humanities in the primary school – philosophical considerations. Education 3–13 45(3): 343–353.

Eaude T (2018) Developing the Expertise of Primary and Elementary Classroom Teachers. London: Bloomsbury.

Eaude T, Butt G, Catling S et al. (2017) The future of the humanities in primary schools – reflections in troubled times. Education 3–13 45(3): 386–395.

Nussbaum M (2010) Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ofsted (2019) Ofsted inspection handbooks: Drafts for consultation. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/ofsted-inspection-handbooks-drafts-for-consultation (accessed 25 March 2019).

Ogier S and Eaude T (eds) (forthcoming) A Broad and Balanced Curriculum in Primary Schools: Educating the Whole Child. London: SAGE.

United Nations (2015) Sustainable development goals. Available at: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed 25 March 2019).

This article was published in May 2019 and reflects the terminology and understanding of research and evidence in use at the time. Some terms and conclusions may no longer align with current standards. We encourage readers to approach the content with an understanding of this context.