How cognitive science underpins curriculum design and digital pedagogy in the Church of England’s NPQs

Jo Lomax, Programme Lead, and Luke Watkins (CTeach), Learning Specialist, Church of England Foundation for Educational Leadership, UK

Context

Reforms to the induction of our newest teachers, through the Early Career Framework (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsi, 2019), and the reformed NPQs (DfE, 2020) for those who aspire to develop expertise in specialist areas and leadership are underpinned by evidence relating to cognitive scienceThe study of the human mind, such as the processes of though and how pupils learn. These changes have been defined by a ‘golden thread’ of high-quality evidence underpinning the support, training and development available through a teacher’s entire career (DfE, 2021). They ‘exemplify a growing consensus that promoting effective professional development (PD) plays a crucial role in improving classroom practice and pupil outcomes’ (EEF, 2021a, p. 4). Alongside this, there is a clear recognition of the importance of teachers understanding and applying the principles of cognitive science in their teaching practice in order to maximise pupils’ learning. As a successful national NPQ lead provider, the Church of England has sought to combine robust unpacking of this evidence, in its carefully sequenced curriculum design, with creative and evidence-led approaches to digital learning experiences that aim to make high-quality professional development accessible and impactful for all.

The language around professional development has changed over the last five years, with many grassroots movements for sharing and learning (such as WomenEd and Northern Rocks), and there appears to be a new way for ‘the profession to learn and collaborate’ (Weston and Clay, 2018 p1). This change is welcome, with some describing it as ‘urgent’, believing that ‘teachers and students are being failed by competing pressures and lack of resources’ (Weston and Clay, 2018 p. 161). However, developing professional development with maximum impact on teachers’ practice is complex. One of the biggest barriers to developing effective professional development is lack of time and resources: ‘teachers engage in professional development activities whilst balancing multiple and, at times, competing commitments and time pressures’ (EEF, 2021a, p. 4). Therefore, it is essential that professional development is well designed, meets the needs of the staff and school, and is implemented so that the investment is justified (EEF, 2021a). The use of digital learning, combined with a balanced hybrid model, could ensure that high-quality professional development provides sufficient flexibility for busy teachers to engage in a more meaningful way, whilst being underpinned by the principles of cognitive science to maximise learning.

Ensuring a balanced professional development design through a four-stage learning model

In ensuring a balanced design, it was essential to first establish the core mechanisms (the building blocks) that would ensure that our NPQ offer positively impacted on the practice of participants. The EEF (2021a, p. 11) explain that ‘Mechanisms provide exact, clear, building blocks for professional development.’ The core mechanisms were determined by drawing on the evidence relating to high-quality teaching practices (EEF, 2021a; Rosenshine, 2012; Deans for Impact, 2015), including, but not limited to, building on prior knowledge, explicit instruction, scaffoldingProgressively introducing students to new concepts to suppor, feedback, effective modelling, practice, questioning and metacognition.

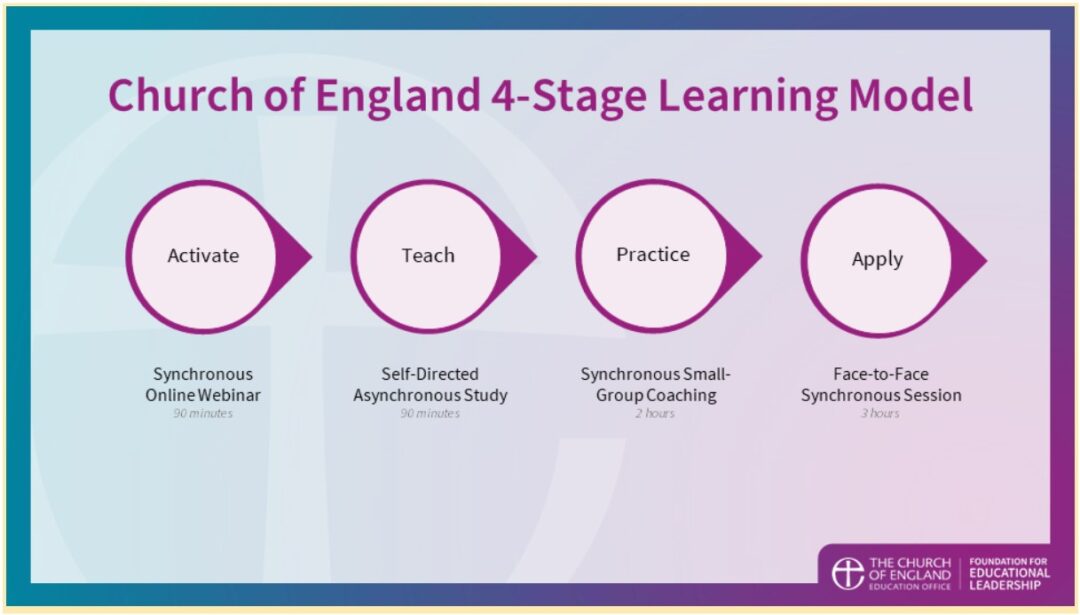

To give a coherent structure to the Church of England’s approach, our four-stage learning model is replicated across each unit (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Church of England four-stage learning model overview

Participants are first introduced to the evidence base through an ‘ACTIVATE’ online seminar, providing an opportunity to consider their prior knowledge and contextualise this in a role-specific way. Participants then build on their existing knowledge and revisit their prior learning through the asynchronous study. This second phase of the curriculum model – ‘TEACH’ – is a detailed synthesis of the DfE evidence base, deliberately chunked into smaller sections to manage cognitive load. Participants are provided with role-specific examples, modelling, exemplifications and reflection opportunities, enabling them to further contextualise their learning.

The third phase of the curriculum model, ‘PRACTICE’, involves small-group coaching. Participants are guided through the ‘Called, Connected, Committed’ coaching conversation. ‘Called’ involves identifying and shedding light on participants’ values as a leader and their sense of calling into the profession ; ‘connected’ pertains to engaging in dialogue to shed light on complex problems utilising research, and ‘committed’ requires participants to identify next steps and commitments, for which they will be accountable. Our model is based on robust evidence relating to deliberate practice, using practice and high-quality feedback to achieve goals (Deans for Impact, 2016); dialogic instructional coaching, where coaches and participants discuss and think together, utilising expert input (Knight, 2017); and evidence-informed practice, whereby research is blended with participants’ lived experiences (Cordingley et al., 2015). To support the focus on evidence-informed practice, coaches are accredited with the Certificate in Evidence Informed Practice by the Chartered College of Teaching which OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services highlighted this as a key strength (Ofsted, 2022).

The fourth stage – ‘APPLY’ – is a face-to-face session where participants meet in their regional cohorts, with a critical focus on knowledge application. The face-to-face sessions provide opportunities to learn from experts through clear and detailed models, exemplification (guided practice) and case-study exploration so that learning can be contextualised across unfamiliar contexts. Through expert facilitation, participants are provided with prompts and cues throughout to understand the evidence base in a role-specific way, and they work towards clearly articulating the key actions that leaders should take to apply evidence-based practices in their own settings.

A hybrid model that blends asynchronous digital learning with face-to-face provision was employed, as it allowed us to build a programme carefully around the needs of professionals with busy schedules, bringing flexibility by delivering the most appropriate content online, whilst also enabling dialogue and discourse at key points. As one participant commented, the online elements ‘make me feel much more confident [about] the workload as I can engage [with them] from school’, while another appreciated the ‘flexible learning’, enabling them to ‘balance childcare, work and the programme’.

Our carefully sequenced curriculum builds on these core principles, whilst building knowledge, motivating teachers, developing techniques and embedding practice (EEF, 2021a).

Building knowledge

We know that our working memories are limited, only retaining four to seven pieces of information for up to 30 seconds (Willingham, 2009). Therefore, our learning content is designed to break down new material into small steps, which are carefully sequenced to revisit prior learning. Opportunities for regular low-stakes quizzing promote retention of information in the long-term memory. This enables the strengthening of mental models and develops the brain’s ability to organise and make connections between items of information (Rosenshine, 2012). Although participants take a summative assessment at the end of their NPQ, ongoing low-stakes quizzing has a greater impact on memory (Rosenshine, 2012; EEF, 2021b). Therefore, we implemented a range of low-stakes quizzes throughout all of our ‘TEACH’ self-directed content, with instant feedback that addresses misconceptions and provides meaningful feedback to curriculum designers where common misconceptions arise. This is particularly pertinent since supporting the development of participants’ long-term memory can be harmed if they are building mental models around misconceptions (Rosenshine, 2012). Participants are therefore encouraged to return to areas where they answered questions incorrectly and revisit prior learning.

Motivating participants

Every stage of the NPQ learning model enables participants to set and agree on goals. Throughout the asynchronous study phase, participants are presented with opportunities to contextualise their learning and consider what it means for them as leaders.

Content has been sequenced in a way that is logical, builds on prior knowledge and provides explicit opportunities for spaced practice and recall (Carpenter and Agarwal, 2020). Content presented online can often feel quite linear in nature; however, this can be beneficial in helping participants to mentally organise their progression within the unit (EEF, 2021b). We know that revisiting concepts, when necessary, can benefit retention in the long-term memory (EEF, 2021b). As a result, low-stakes quizzes are embedded across each NPQ, which provide reinforcement after progress has been made (EEF, 2021a). Participants have access to a comprehensive research synthesis that is derived from credible sources. Participants can access this content at any time from a desktop or mobile device, affording additional flexibility for future engagement with the evidence base.

Developing teaching and leadership techniques

The four-stage learning model balances instruction (through the ACTIVATE and TEACH phases), with monitoring, feedback (through the PRACTICE coaching phase) and modelling (through the APPLY phase). Each of these elements are underpinned by social support, where participants engage in their learning with colleagues from across phases and contexts.

Embedding practice

The four-stage learning model encompasses the importance of putting theory into practice. The curriculum has been carefully crafted to provide prompts and cues, utilising existing high-quality models, vignettes and case studies (such as those provided by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), Evidence Based Education’s Great Teaching Toolkit and the Research Schools Network). Action planning is embedded through the PRACTICE coaching and APPLY phases, where participants are presented with a range of ‘problems’ or ‘challenges’ that deepen their thinking and check for understanding. Context-specific repetition is encouraged through the reflection prompts and knowledge engagement questions.

Enhancing high-quality professional development in schools with digital learning

Digital learning experiences can offer significant benefits in terms of flexibility, particularly given the increasing time pressures and workload of school leaders (Jerrim and Sims, 2018), yet professionals can at times be sceptical that effective pedagogy can be implemented in a virtual way. Indeed, research suggests that online learning presents challenges, such as enabling effective collaboration opportunities (Seymour-Walsh et al., 2020). However, there is increasing evidence that technology can be used in a hybrid way to enhance in-person learning; for example, using technology to co-construct work on interactive whiteboards (Mercer et al., 2010) or share ideas through virtual ‘sticky notes’ (Morozov et al., 2014). Mishra and Koehler (2006) argue that digital learning comprises three overlapping domains: pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge and technological knowledge. It is this overlap that underpins the relationship between our four-stage learning model and the digital learning experiences that are embedded across all our programmes.

To address the challenge of time and resource limitations, those who design and deliver professional development should consider the use of digital technology as a tool that affords flexibility to the process. Indeed, there are some digital learning platforms already available, such as the Great Teaching Toolkit (Evidence Based Education (nd). Alternative examples include the use of Google Drive or SharePoint, to share evidence-informed think pieces or resources in advance of face-to-face sessions. Schools may also consider the wider benefits of using the video conference software that was utilised so brilliantly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Video conference software (such as Zoom, Teams or Google Meet) can be more time-efficient, while still providing opportunities for collaboration and interactivity. Breakout rooms and an on-screen ‘whiteboard’ (such as Microsoft Teams Whiteboard and Google Jamboard) enable participants to co-construct an online document, underpinned by the idea that learning is a collaborative process (Vygotsky, 1978).

Conclusion

Hybrid learning models often face criticism within the sector (Woolcock, 2021), therefore developing robust and effective programmes of hybrid professional development requires careful consideration. Designing a curriculum that ensures fidelity to national frameworks has been a significant undertaking. However, Ofsted (2022, p4) commented that the Church of England have ‘developed an effective and ambitious curriculum across all NPQ programmes’ that is ‘consistently well supported by high-quality and meticulous training materials and resources’, demonstrating that it is indeed possible to create hybrid models of professional development that are underpinned by cognitive science. Where schools are time- and resource-limited, encouraging staff to participate in the NPQs will enable more teachers and school leaders to engage in high-quality professional development, benefitting both them and their pupils.

With thanks to Liz Barratt, Director of Adult Learning, Transform Trust, UK.

- Carpenter S and Agarwal P (2020) How to use spaced retrieval practice to boost learning. Retrieval Practice. Available at: http://pdf.retrievalpractice.org/SpacingGuide.pdf (accessed 8 September 2022).

- Cordingley P, Higgins S, Greany T et al. (2015) Developing great teaching: Lessons from the international reviews into effective professional development. Teacher Development Trust. Available at: https://tdtrust.org/about/dgt (accessed 8 September 2022).

- Deans for Impact (2015) The Science of Learning. Austin, TX: Deans for Impact.

- Deans for Impact (2016) Practice with Purpose: The Emerging Science of Teacher Expertise. Austin, TX: Deans for Impact.

- Department for Education (DfE) (2019) Early career framework. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/978358/Early-Career_Framework_April_2021.pdf (accessed 17 November 2022).

- Department for Education (DfE) (2020) National professional qualification (NPQ): Leading teaching framework. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/925513/NPQ_Leading_Teaching.pdf (accessed 8 September 2022).

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2021a) effective professional development: Guidance report. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/guidance-reports/effective-professional-development (accessed 7 July 2022).

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2021b) Cognitive science approaches in the classroom. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/evidence-reviews/cognitive-science-approaches-in-the-classroom (accessed 7 September 2022).

- Evidence Based Education (nd) The Great Teaching Toolkit. Available at: www.greatteaching.com (accessed 17 November 2022).

- Jerrim J and Sims S (2018) The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018: Research report. Department for Education. Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/33612/1/TALIS_2018_research.pdf (accessed 8 September 2022).

- Knight J (2017) The Impact Cycle: What Instructional Coaches Should Do to Foster Powerful Improvements in Teaching. London: SAGE.

- Mercer N, Hennessy S and Warwick P (2010) Using interactive whiteboards to orchestrate classroom dialogue. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 19(1): 195–209.

- Mishra P and Koehler M (2006) Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record 108(1): 1017–1054.

- Morozov M, Smorkalov A and Fominykh M (2014) Sticky notes: A tool for supporting collaborative activities in a 3D virtual world. In: IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Athens, Greece, 7–14 July 2014, pp. 683–687.

- Ofsted (2022) Lead Provider Monitoring Visit (LPMV) of the Church of England. Available at: https://files.ofsted.gov.uk/v1/file/50190901 (Accessed on: 1st December 2022).

- Rosenshine B (2012) Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator 36(1): 12–19, 39.

- Seymour-Walsh A, Weber A and Bell A (2020) Pedagogical foundations to online lectures in health professions education. Rural and Remote Health 20(1): 6038.

- Vygotsky L (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

- Weston, D, and Clay, B (2018) Unleashing Great Teaching: The Secrets to the Most Effective Teacher Development. Routledge: London.

- Willingham D (2009) Why Don’t Students Like School? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Woolcock N (2021) Universities ordered to teach face to face. The Times, 10 September, 21. Available at: www.thetimes.co.uk/article/universities-ordered-to-teach-face-to-face-jb63cjkz2 (accessed 8 September 2022).