This case study is part of a series of short online learning courses on decolonising and diversifying the curriculum. Chartered College of Teaching members can access this learning for free.

This is a case study from Module 4, ‘Approaches to decolonising and diversifying the curriculum’, of a series of 6 online courses. The module includes a variety of case studies about the principles and approaches that might underpin work to meaningfully decolonise and diversify the curriculum.

No matter the phase of education, the aim of decolonising and diversifying is to actively dismantle a narrative that has long favoured a white, male, cis, heterosexual, non-disabled, Eurocentric view of the world, and instead, adjust and widen the lens and give space to those who have been marginalised, ignored or denied and have had their histories skewed or rewritten. Intersectionality is another key issue to consider. The Lawrence Review (2020) which focused on Covid-specific issues, highlighted that the virus had ‘thrived on structural inequalities that have long scarred British society’ (Lawrence, 2020, p. 24). With more than half of Black children in the UK growing up in poverty (Tobin, 2021), it is unsurprising that recommendations from the review included having clear targets to close the attainment gap and for employers to publish data on pay gaps. As early years educators, we know the impact we can make – there is a moral imperative to actively make a change.

To begin this work, an audit of the curriculum and provision we have in place is essential. Decolonisation and diversifying must not be ‘bolt on’ (Kara, 2020, p. 64). We are aiming for ‘usualisation’, a term I was introduced to through Bennie Kara’s work (2020), that she acknowledges came from Sue Sanders of Schools Out UK. However, this is not easy. There must be an acceptance that we are likely to have to become increasingly comfortable with being uncomfortable. To truly audit curricula, we must consider our own biases. We are products of the system. Who were our teachers? What might we need to unlearn? What biases do we need to be self-aware of? What is being taught? Who is taking centre stage? Who is in the shadows?

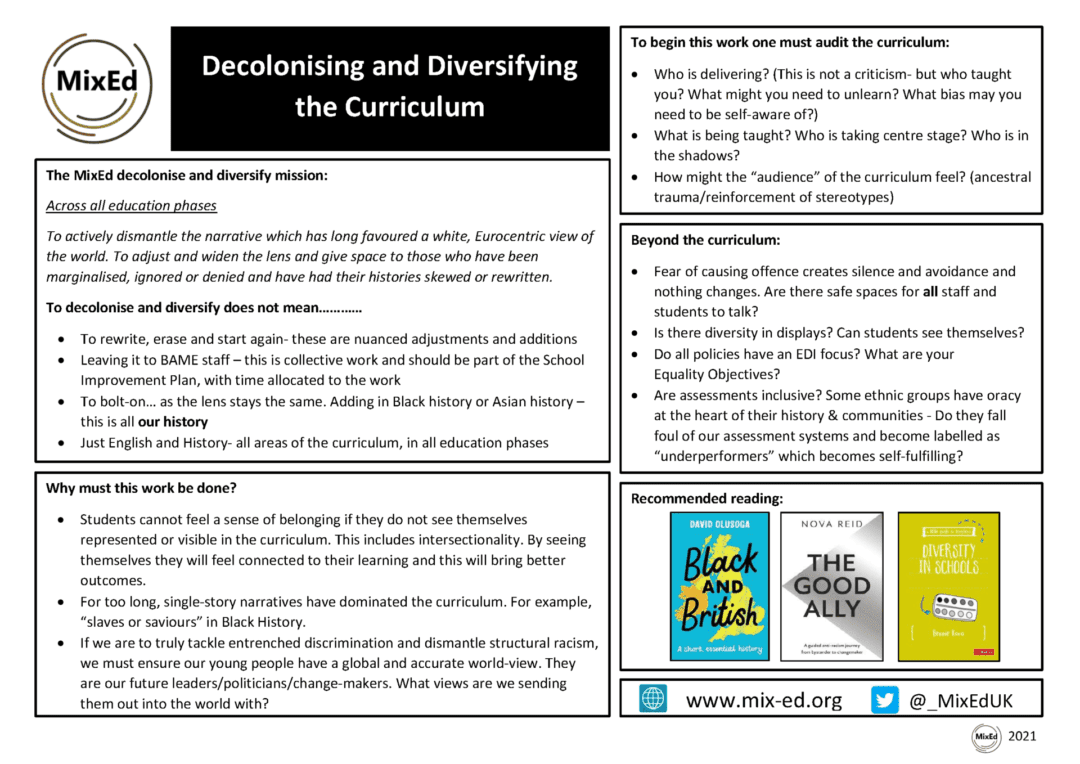

I am proud to be part of a working group for MixEd who are looking at how we can support both the decolonisation and diversification of the curriculum movements at a practical level. The aim is to work towards ‘usualisation’. We have created the free resource shared below as a starting point, with a focus on raising awareness and asking initial questions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Decolonising and diversifying the curriculum resource (MixEd)

We can begin to challenge our biases, and those of the society we live in, by just being aware of issues around diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences as we go about our everyday lives. Next time you are out shopping, try the following exercise: walk into a toy shop and consider the extent to which gender differences are created by the way we treat boys and girls. There is often an immediate visual difference. Aisles are segregated, not only by colour, but also by content. For younger children, dolls and soft toys dominate the largely pink aisles. There are fewer toys that provide opportunities for spatial awareness or physical confidence – those toys are usually separated, often in bold primary colours. Now consider any trends in strengths we see in our on-entry data. Is there a difference between girls and boys? If so, in which areas? Perhaps even more illuminating, moving beyond our settings, consider trends in the workforce. Men dominate careers prizing maths, spatial awareness and physical confidence. Women make up just 23 per cent of the STEM workforce (Statistica, 2019). Is this a case of nature or nurture? Now consider our settings, is there equality of opportunity for all types of toys, games and play? When children play spatial awareness games frequently, their brains change physically within three months (Zhang et al., 2014). How many of our children already have preconceptions about what is for boys and what is for girls?

Our own biases are passed on to our children and the cycle repeats. None of us are immune to this, even when we are part of a group negatively impacted by stereotypes. In 1940’s America, during a time of segregation and the civil rights movement, Kenneth and Mammi Clarke developed a psychological test, now referred to as ‘the doll test’. They found that given a choice between Black dolls and white dolls, most Black children had a bias towards the white doll. They associated positive characteristics with the white dolls and negative characteristics with the Black ones. In the final question, children were asked to identify which doll looks most like them. Having watched this play out thousands of times like in the video example referenced, I still find it impossible not to become upset. The learning from this? We are all a product of colonisation. None of us are immune.

‘Whiteness positions itself as the norm. It refuses to recognise itself for what it is. Its so-called ‘objectivity’ and ‘reason’ is its most potent and insidious tool for maintaining power. … It is a problem, because we consider humanity through the prism of whiteness’. (Eddo-Lodge, 2019, p. 169)

| Reflection: The doll test |

| Watch an example of the doll test. Consider the impact on children. There are enough social cues in our society that even the group impacted by racism can harbour and internalise negative stereotypes. Consider how the images we choose and display in our settings can begin to challenge this narrative. Where is there visible diversity? |

To decolonise and diversify does not mean to rewrite, erase and start again. Instead, these processes call for nuanced adjustments and additions. Is there diversity in wall displays? Can students see themselves in the books we read and resources we choose? Do all policies have an equality, diversity and inclusionAn approach where a school aims to ensure that all children are educated together, with support for those who require it to access the full curriculum and contribute to and participate in all aspects of school life focus? What are your equality objectives? This is collective work and should be part of a development plan, with time allocated to the work. In settings I have worked in, we have created working parties consisting of staff from all levels to focus on specific areas. Diversifying our literature is an example. The working party considered the national picture. They found that the number of children’s books published in the UK between 2017 and 2019 featuring characters from a Black, Asian or minority ethnic background had increased to 10 per cent in 2019, rising from 4 per cent in 2017 (CLPE, 2021). They audited our own collection and found it lacking – not all children would see themselves in our stories. Next, they explored examples of effective practice – who was doing this well? They found several resources, including the ‘I See Me’ inclusive picture books list compiled by Mister Bodd, a website run by Dean Boddington, a Key Stage 1 teacher. Samples of these books were bought or borrowed and the whole staff team chose books they felt were important. Crucially, in this model, staff were empowered to research, lead and make the change.

| Reflection: ‘I See Me’ literature audit |

| In your current setting, conduct a literature audit. Look at each book in your collection and track what identities the author and main character hold. Record these details in a spreadsheet (or by using this audit tool) to identify where your collection still needs to grow. You can find good examples of texts which include diversity from Mister Bodd’s blog. |

Being open to learning is key. Fear of making a mistake can feel overwhelming and hinder the process of learning about and discussing other cultures. However, there is power in modelling the learning journey. Showing that we are all unique and valued is empowering for both us and our children. The starting point is creating awareness. There is literally something to celebrate every day of the year. In the same way, we have built in discussing the day, week, month, season and whether we can build in celebrating diversity from around the globe. For example, you could access a cultural planning calendar and consider which religious days you will celebrate.

This work is a process, and the first part of that process is acknowledging that we are likely going to need to unlearn some of what we thought we knew. It begins with a journey of self-education. We would not enter our settings ready to facilitate learning and play opportunities about early language, numeracy or indeed any area of the curriculum without first knowing about it ourselves. Decolonising and diversifying is no different. Thankfully there is help at hand. There is a wealth of excellent texts that can help us to face our implicit biases. In my opinion, there is no better place to start than Nova Reid’s The Good Ally (2021). When it comes to making practical change, support comes from Dr Pragya Agarwal’s Wish We Knew What to Say: Talking with Children About Race (2020), Bennie Kara’s A Little Guide to Diversity in Schools (2020), and Sameena Choudry’s Equitable Education (2021).

For too long, both in society and in the education sector, we have been comfortable with the status quo in terms of race and diversity. After all, we are good people, we care about children, we are certainly not racist and we want to improve lives. We are the good ones… aren’t we? As Nova Reid reminds us in The Good Ally:

‘Society has become really good at dehumanising… racism has got nothing to do with being a good or bad person. It means facing up to the fact that what we’ve been taught to believe about ‘racists’ – being exclusively abhorrent, probably unintelligent and definitely violent individuals – is false. (p. 29)’

People who want to cause harm are in the minority. Kind-hearted, well-intentioned people are in the powerful majority. People like you.